EN LIGNE DE MIRE

La paralysie de la volonté

Guerre en Ukraine

Et si Macron avait raison ?

La petite phrase d’Emmanuel Macron suggérant aux Européens de ne pas écarter l’idée de mettre des troupes au sol en Ukraine a fait couler beaucoup d’encre et n’a laissé aucun pays allié indifférent. Il n’a pas fallu longtemps pour constater que cette unanimité dans la condamnation se transforme en un soutien discret, de quoi irriter Vladimir Poutine… Il aura suffi d’une semaine pour constater qu’il n’y avait pas que les Baltes, les Tchèques ou les Polonais, pour penser que la gravité de la menace d’une défaite de l’Ukraine méritait bien que l’on se pose sérieusement certaines questions. Dans les pays du Nord égale-ment, l’idée a rapidement trouvé une résonnance comme cela a été le cas aux Pays-Bas. La publication ce jour d’une analyse de Britta Sandberg dans le Spiegel, le plus grand des magazines allemands, a été accueillie avec un soulagement et une surprise mal dissimulés. Nous reproduisons ici cet article avec l’autorisation de son auteure. […]

« Les États européens ont les moyens de résister à la pression russe »

il est inéluctable que la situation s’aggrave dange-reusement aux frontières de l’Union européenne et de l’OTAN… Si Poutine pouvait l’emporter sans guerre frontale, en visant les lignes de moindre résistance de l’Occident et en s’appuyant sur les forces internes de dislocation qu’il contrôle, il ne s’en priverait pas. Rappelons que ce n’est pas l’envahisseur d’un pays qui déclenche la guerre, mais la résistance armée du pays visé par l’agression. Dans De la guerre, Clausewitz mentionnait cette vérité, ce qui avait beaucoup amusé Marx et Engels (ils ont annoté l’exemplaire consulté). En d’autres termes, si vous voulez éviter la guerre, la chose est simple : « Soumettez-vous ». Cette petite musique s’entend déjà derrière les appels à la « désescalade ». Mais qui donc pratique l’escalade sinon Poutine et les hommes qui dirigent la Russie-Eurasie ? […]

Ukraine : rupture ou continuité ?

Un fort sentiment d’inquiétude commence à se manifester face à la guerre d’Ukraine parmi les dirigeants français et européens, mais également au niveau de l’opinion publique. Ce sentiment est sans doute à l’origine du quasi retournement des positions affi-chées par le président de la République en France…

Nous appelions, il y a quelques mois déjà, à la définition d’une stratégie des pays occidentaux face à la Russie, complète et unifiée, qui irait au-delà du simple objectif de l’empêcher de gagner, pour s’accorder sur des objectifs positifs, collectivement approuvés, dont le but serait de briser l’agres-sion russe, sur le plan des moyens, mais également, et plus fondamentalement, sur celui de la volonté d’agression, objectif plus difficile à atteindre, mais sans lequel l’arrêt de l’action militaire ne peut être qu’un état provisoire, donc précaire. […]

LES DERNIÈRES CHRONIQUES

Tel père, tel fils : le premier compagnon et le dernier

« Il faut agir au-delà de soi et travailler pour plus grand que soi » … « Comme il est dur, pourtant, d’être De Gaulle après De Gaulle, d’en avoir l’allure, la voix, les gestes et de ne pas être lui. L’Amiral répondait aux murmures par la rigueur de sa conscience, son indifférence à la mondanité, déclinant toute prési-dence parlementaire ou honorifique, quelle qu’elle fût. Dans son œuvre de mémorialiste, il montrait toujours la grandeur collective, et non la sienne, effaçant ses hauts faits derrière ceux des autres. Le témoin expliquait l’Histoire, l’officier expliquait le combat, l’Amiral expliquait le Général.» Il y a des moments où une Nation se retrouve. Ce fut le cas lors de l’hommage rendu à l’amiral Philippe de Gaulle dans la cour d’honneur des Invalides. Les mots choisis par le président Emmanuel Macron pour honorer la mémoire et le parcours hors-normes de ce grand soldat ont été une occasion de renouer avec le temps long cher aux militaires.

[…]

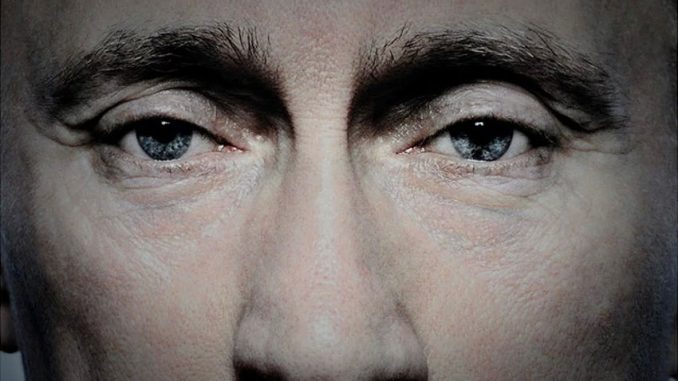

Black Days Continued (vol.5): Media Repression in Russia

Censorship, conveyor-belt sentencing, gangster attacks, economic suffocation and waterfalls of disinfo flooding public discourse: revanchist, militant nationalism is drowning the Russian information space. The last remaining pretence of media freedom in Russia is quickly falling away. The suspicious death of Alexey Navalny has left Russian leader Vladimir Putin with few if any viable domestic opponents, and he seems to relish his strongman image. His state-of-the-nation address on 29 February set a new tone in the Kremlin’s information operations: that of a dictator seemingly confident that no one would dare oppose him. For Russians who believe that their country should be free, open, and prosperous, the current moment is bleak. As one mourner for Navalny said, ‘I don’t have any vision of the future.’… Putin’s institutionalised wrath against all his real or perceived enemies, continues to get crueller, pettier, deadlier, faster. […]

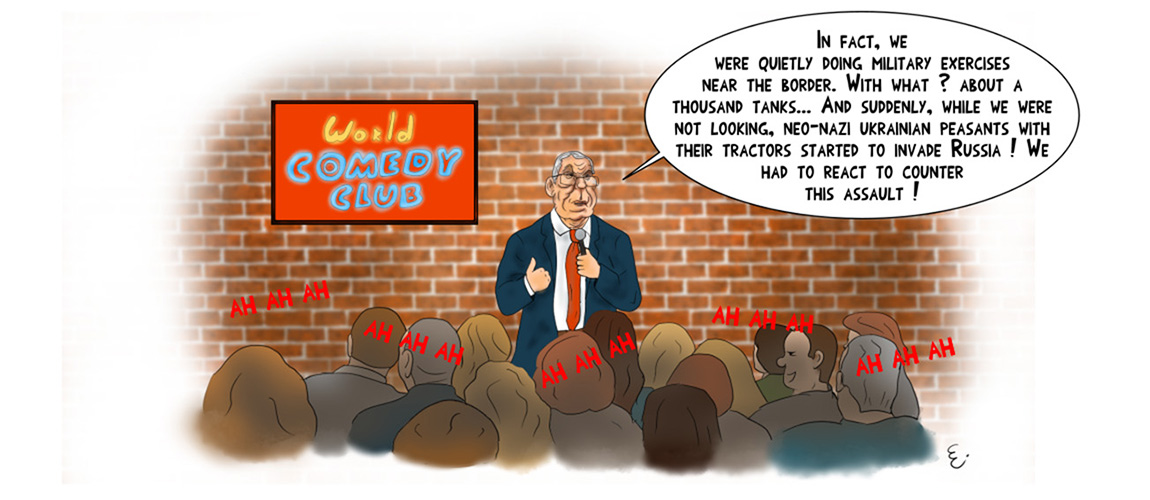

Force Feeding Fears and Summoning Bogeymen

This week, as the Czar awaits his re-crowning after a so called ‘election’ rigged in his favour, the pro-Kremlin propaganda apparatus has been busy crafting an alternative reality. As the Russian armed forces failed miserably to produce anything worth celebrating, the propagandists have resorted to age-old fear tactics, painting a picture of a world filled with threats, where Russia is under attack and enemies are already at the gates. It also sets the scene for the next chapter of Putin’s rule. The imagery invoked aims to trigger primal reactions that can be harnessed for the Kremlin’s post-‘election’ purposes… The pro-Russian disinformation eco-system has continued to push cynical lies that Russia does not strike civilian targets. This time, the claim was presented in the context of the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) decision to issue arrest warrants for 2 high-ranking Russian military officers. […]

« Les États européens ont les moyens de résister à la pression russe »

il est inéluctable que la situation s’aggrave dange-reusement aux frontières de l’Union européenne et de l’OTAN… Si Poutine pouvait l’emporter sans guerre frontale, en visant les lignes de moindre résistance de l’Occident et en s’appuyant sur les forces internes de dislocation qu’il contrôle, il ne s’en priverait pas. Rappelons que ce n’est pas l’envahisseur d’un pays qui déclenche la guerre, mais la résistance armée du pays visé par l’agression. Dans De la guerre, Clausewitz mentionnait cette vérité, ce qui avait beaucoup amusé Marx et Engels (ils ont annoté l’exemplaire consulté). En d’autres termes, si vous voulez éviter la guerre, la chose est simple : « Soumettez-vous ». Cette petite musique s’entend déjà derrière les appels à la « désescalade ». Mais qui donc pratique l’escalade sinon Poutine et les hommes qui dirigent la Russie-Eurasie ? […]