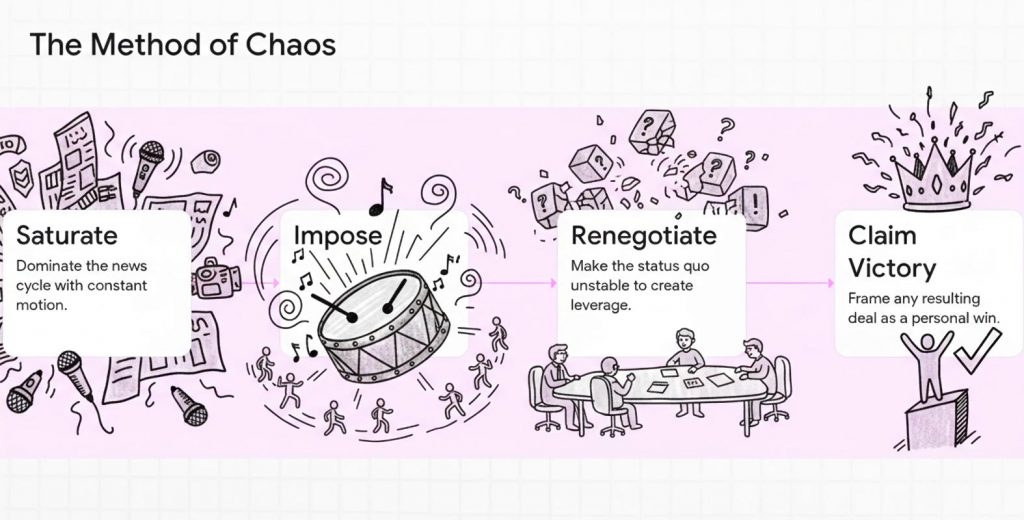

Editor’s Note: As a direct echo to our paper on ‘The Great Rupture,’ which laid out the geopolitical diagnosis confirming the end of automatic transatlantic alignment, this second text by Jérôme Denariez brilliantly decodes the tactical modus operandi of this new era. The author invites us to move beyond an emotional reading of the ‘Trump style’ to see a cold method: ‘useful chaos.’

Here, unpredictability is not a pathology, but a tactical weapon designed to flood the zone, paralyze the adversary, and transform uncertainty into a lever for negotiation (tariffs, NATO).

However, Jérôme Denariez nuances this finding: while this grammar of disruption has historical precedents (from Nixon’s ‘madman theory’ to Roosevelt’s big stick), Trump personalizes it to the extreme. This is where the danger identified by the author lies: this shock strategy offers rapid gains but erodes over time, pushing China toward autonomy and leaving allies without a compass. For Europe, the message of this diptych is scathing: faced with an America that turns disorder into a doctrine, ‘legal comfort’ is no longer enough; it is time to step back into the arena of power dynamics.

Table of Contents

by Jérôme Denariez — Paris, January 24, 2026

Introduction

Trumpian disorder has too often been treated as a political pathology, and therefore as an accident. Yet there is another reading—colder, less moral, and ultimately more worrying.

Chaos can be a tool. Not just a symptom.

The question is not, therefore, whether Donald Trump is unpredictable. He is. The question is whether this unpredictability is merely noise, or if it is becoming a method, and above all, if this method is sustainable. Because a weapon that depends on a single man is not a doctrine. It is a window.

This paper proposes a simple hypothesis. The United States did not wait for Trump to wield power through disruption. But Trump pushes the slider; he exposes it, he personalizes it. And it is precisely this mixture that makes the strategy effective in the short term, fragile in the long term, and difficult to transmit.

I. Trump and the Installation of Chaos: Chaos Manufactured, then Exploited

There is a very particular art of disorder with Trump. It is not just about unpredictable decisions. It is about a way of occupying space.

He saturates attention. He constantly shifts the center of gravity. He forces allies and adversaries to live in reaction. He imposes a rhythm where the other side spends its energy trying to understand the last move, instead of preparing for the next one.

There is a thought-out chaos, when it serves as a signal of rupture, when it serves to raise the stakes, when it serves to force a renegotiation.

We saw this in the way Trump has, on several occasions, stirred uncertainty around NATO. The objective is not necessarily to leave, but to make the threat credible, to shift budgetary lines, and to install the idea among allies that American protection is no longer an automatic reflex.

We also saw it when he used the trade weapon as a political lever, for example by threatening Mexico with tariffs in 2019 to obtain a crackdown on migration. Public threat, calculated panic, accelerated negotiation, then a “deal” presented as a victory, in a sequence where trade is no longer a subject in itself, but an instrument of coercion.

Finally, we see it in assumed symbolic ruptures, such as the announcement of withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in 2017, and the decision to withdraw signified again at the very beginning of the second term in 2025. Here, the rupture is not collateral damage; it is a message, addressed as much internally as externally, about the end of a regime of constraints.

And there is an opportunistic chaos, when the moment dictates the decision, when an opening appears and is seized without scruples, when a power dynamic is exploited because it is available.

The elimination of Qasem Soleimani in January 2020 illustrates this logic of the “strike.” A rapid decision, an immediate global effect, a calculation of deterrence, and an instant rise in the risk of escalation, with the certainty that the strategic environment will be recomposed within twenty-four hours.

More broadly, Trump has systematized the use of tariff threats as a lever for negotiation, to the point of transforming volatility into an instrument.

The announcement, the retreat, the relaunch become successive movements; the other side then comes to “buy” predictability, because uncertainty itself becomes the central cost. In both cases, the outside world receives the same message. The rules are not stable. Your word is not a contract. Surprise is a weapon.

It is no coincidence that this grammar resembles that of certain business worlds, and particularly New York real estate. Lawsuits, pressure, the threat of breaking it off, the sudden reversal, the deal presented as inevitable. These are reflexes more than doctrines. Trump is not reading a manual. He is playing a hand. And it is precisely this mixture that produces a strategic effect. A method born of a temperament, amplified by access to the State.

II. Has the US Always Operated This Way? By Episodes, with Different Styles

To say that America has always governed by chaos would be false. To say that it has never done so would be naive.

There are, in American history, recurring episodes where unpredictability becomes an instrument. It changes shape depending on the presidents. It changes degree. It changes packaging. But it returns.

Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis show a power that maintains a legible public posture, but works in parallel through discreet channels, signals, and partially invisible compromises. This is not spectacle chaos. It is controlled chaos, below the surface, in the service of resolving a crisis.

Nixon pushes the idea of unpredictability as a lever further. He accepts being perceived as capable of going too far. He uses ambiguity, psychological pressure, vagueness about escalation. The most telling episode remains the “madman theory” and, in its operational version, the idea that a demonstration of nuclear readiness could weigh on a diplomatic balance of power.

Theodore Roosevelt, finally, illustrates another register. That of a hardened Monroe Doctrine, where the Western Hemisphere becomes a space of policing and constraint, with a doctrinal legitimation of intervention. It is a power that assumes its zone, and sets the rules there. (And this point is useful because it allows for a proper comparison of a contemporary “Donroe” doctrine to an old American grammar.)

Then come presidents that Europe has strongly criticized.

Reagan, because Europe sometimes experienced his moment of power as an escalation, even when the objective was deterrence. Bush Jr., because Iraqi unilateralism lastingly fractured the transatlantic relationship.

And there are the presidents who were tolerated more, or at least deemed workable.

Clinton, Obama, Biden. They were criticized for decisions, operations, methods. But their power remained generally more readable, more processed, more compatible with the language of allies. Even when the action was harsh, it was wrapped in a framework.

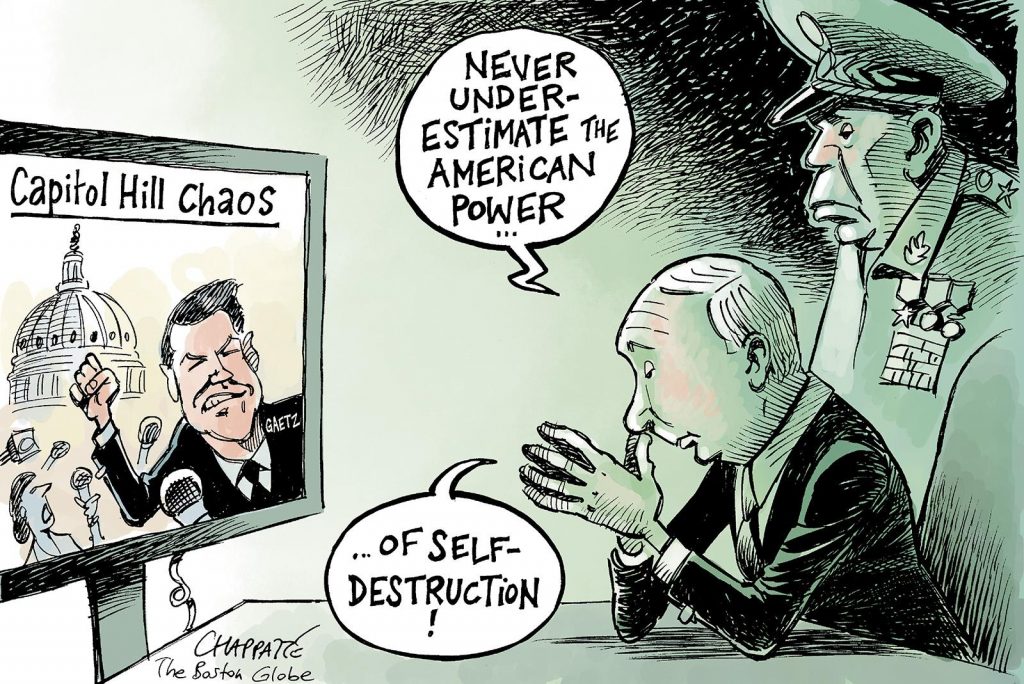

Europeans do not tolerate the United States because they are gentle. They tolerate them when they are readable, when the rules of the game are understandable, even if they are rough. The question is not kindness. It is predictability. And Trump, precisely, attacks this comfort.

III. Continuity of the Apparatus: Reducing Variance, Absorbing Cycles

This is not a fantasy. It is an institutional reality. A great power cannot be summed up by one man, even when that man occupies the entire screen. There is an apparatus. There are routines. There are continuities.

Intelligence, defense, diplomacy, Treasury. These are systems that reduce the variance between administrations, even when they are politically opposed. The president imprints a style, a degree of exposure, a level of delegation. But the machine continues.

Visible political chaos can serve as a screen. It can cover colder, more continuous, more discreet action. The noise absorbs attention. Meanwhile, the apparatus works.

IV. The Fragility of Chaos: A Weapon with Diminishing Returns

Useful chaos has a structural problem. It wears out.

First, the adversary learns. Once unpredictability becomes a habit, it ceases to be a surprise. It becomes a style. And a style, by definition, is legible. Even if it is brutal.

Next, allies hedge. Partners, when they live too long in uncertainty, diversify, protect themselves, rebuild margins of autonomy. They do not necessarily break away. But they cease to depend.

We see this in the very clear rise, in Europe, of the notion of strategic autonomy, which is not just a slogan. It translates an adaptation: planning for the hypothesis where transatlantic alignment is no longer automatic, and where American continuity becomes an uncertain parameter, and thus a risk to manage.

We also see it in concrete budgetary and capability decisions, which stem from a logic of hedging rather than a mere announcement effect. Denmark, for example, is strengthening its Arctic posture in a context where the Greenland question has become politically flammable again, and where American pressure itself becomes a planning factor.

Finally, we see it in the way allies seek to re-solidify red lines when American uncertainty touches allied territory. The sequence in early January 2026 around Greenland provoked public and coordinated political reactions in Europe, and even a stance from Canada reminding that the future of the island is a matter for Denmark and Greenland. This is not a rupture, but it is a signal: the “floor of trust” is no longer considered intangible.

Finally, chaos creates internal costs. Institutional, economic, diplomatic. There is no free power. The question is not whether these costs exist. The question is whether short-term efficiency compensates for them, and if this compensation is sustainable.

Nixon is a good historical test. Unpredictability can move a situation. But it does not guarantee that the adversary yields. They can choose to endure. They can choose to stall. They can bet on the political cycle.

V. China, or the Long Game Test: When Chaos Accelerates Empowerment

Faced with regimes dependent on a flow, a price, a rent, chaos can be an effective lever. It triggers rapid cracks. It weakens the opposing coalition. It forces choices.

Faced with China, the problem changes.

China thinks in long horizons. Economically, industrially, technologically, politically. It invests, it plans, it absorbs shocks, it reconfigures its dependencies. It accepts costs today for an advantage tomorrow.

This is exactly the terrain where chaos can backfire. Because chaos is an accelerator. The question is what it accelerates: It can accelerate capitulation if the adversary is fragile. It can accelerate empowerment if the adversary is patient. If American strategy becomes too unpredictable, too brutal, too exposed, it can offer Beijing an argument and an engine. An internal argument, that of sovereignty. An economic engine, that of substitution.

There is then a strategic risk. By trying to be elusive, one becomes legible. By trying to surprise, one creates a routine of surprise. And a routine can be countered.

VI. Republican Succession: Possible Heirs, Uncertain Legacy

The succession is not written. There are names, but a guarantee is missing. The capacity to take over a method that depends, by nature, on an incarnation.

J.D. Vance. He can inherit part of the political bloc and part of the rhetoric. But he does not automatically inherit the main weapon, which is the personal credibility of the unpredictable, built on years of public transgressions.

Ron DeSantis. He embodies more of a logic of combative, structured, disciplined governance. It is a hardness that is more legible, more “executable,” therefore less “chaos.”

Nikki Haley. She represents rather a more classic Republican line on alliances and diplomacy, therefore more compatible with a legible power, but less compatible with coercion based on unpredictability and permanent rupture.

Donald Trump Jr. He can claim to embody the brand. But the brand is not enough to produce the same credibility of execution, nor the same capacity to impose a rupture as a fait accompli.

One can inherit an electorate. One can inherit a vocabulary. One can inherit certain reflexes. But inheriting a strategy based on embodied unpredictability is much more difficult. Copying the posture risks making it legible. And if it becomes legible, it loses part of its value.

Conclusion: Europe, in the Middle, Without Tea or Illusions

One can hate Trump, admire him, or caricature him. This is of little strategic interest. The interest lies elsewhere.

The interest is to understand that disorder can be a tool of power. That the United States has already practiced it, in different forms. That Trump makes a more exposed, more personal, more transactional version of it. And that this version is effective in the short term, but fragile in the long term.

Faced with this, Europe has a choice

Either it continues to shelter behind a reassuring idea, that of a legal order that would impose itself by its sole legitimacy. Or it accepts that the world also functions through power dynamics, through flows, through undeclared tools, and that it must therefore build its own levers.

Useful chaos is not a spectacle. It is a test.

A test for adversaries, who must learn to endure. A test for allies, who must learn to cover themselves. A test for America itself, which must decide if it wants a transmissible doctrine or a personal weapon.

And a test for Europe, which must choose if it wants to stay on the balcony, or step down into the arena.

Jérôme Denariez

Sources

[01] NATO – Trump’Speech at NATO Summit 2018 (U.S. Mission to NATO)

[02] Menace de tarifs contre le Mexique (The Guardian, 7 juin 2019)

[03] Menace de tarifs contre le Mexique (Texas Tribune, 7 juin 2019)

[04] Retrait de l’Accord de Paris (Columbia Law School – Sabin Center)

[05] Retrait de l’Accord de Paris (Maison Blanche – Executive Order, 20 janv. 2025)

[06] Retrait de l’Accord de Paris – Analyse CRS (Congress.gov, 14 avr. 2025)

[07] Retrait de l’Accord de Paris – Reuters (20 janv. 2025)

[08] Élimination de Qassem Soleimani – Reportage (The Guardian, 3 janv. 2020)

[09] Élimination de Qassem Soleimani – Contexte et réactions (TIME, 3 janv. 2020)

[10] “Madman theory” – Synthèse (Wikipedia)

[11] Opération Giant Lance / alerte nucléaire 1969 – Synthèse (Wikipedia)

[12] “Nixon’s Nuclear Ploy” (National Security Archive, GWU)

[13] Autonomie stratégique européenne – Note EUISS (PDF, 2018)

[14] Autonomie stratégique et “Trumpism” – Article académique (Springer, 2025)

[15] Groenland / tensions et réactions européennes (The Guardian, 6 janv. 2026)

[16] Groenland / réaction danoise et enjeu OTAN (AP News, 6 janv. 2026)

[17] Groenland / position du Canada (Reuters, 6 janv. 2026)

[18] Danemark “crisis-mode” / Groenland (CNBC, 2026)

See also:

- « Europe-États-Unis : la grande rupture » — (2026-0124)

- « Le chaos utile : Constante américaine, style Trump, ou impasse stratégique ? » — (2026-0124)

- « Useful Chaos: American Constant, Trumpian Style, or Strategic Dead End? » — (2026-0124)

- « Nützliches Chaos: Amerikanische Konstante, Trump-Stil oder strategische Sackgasse? » — (2026-0124)