Source — EUvsDiSiNFO — March 10, 2023 — Listen to this article —

Table of Contents

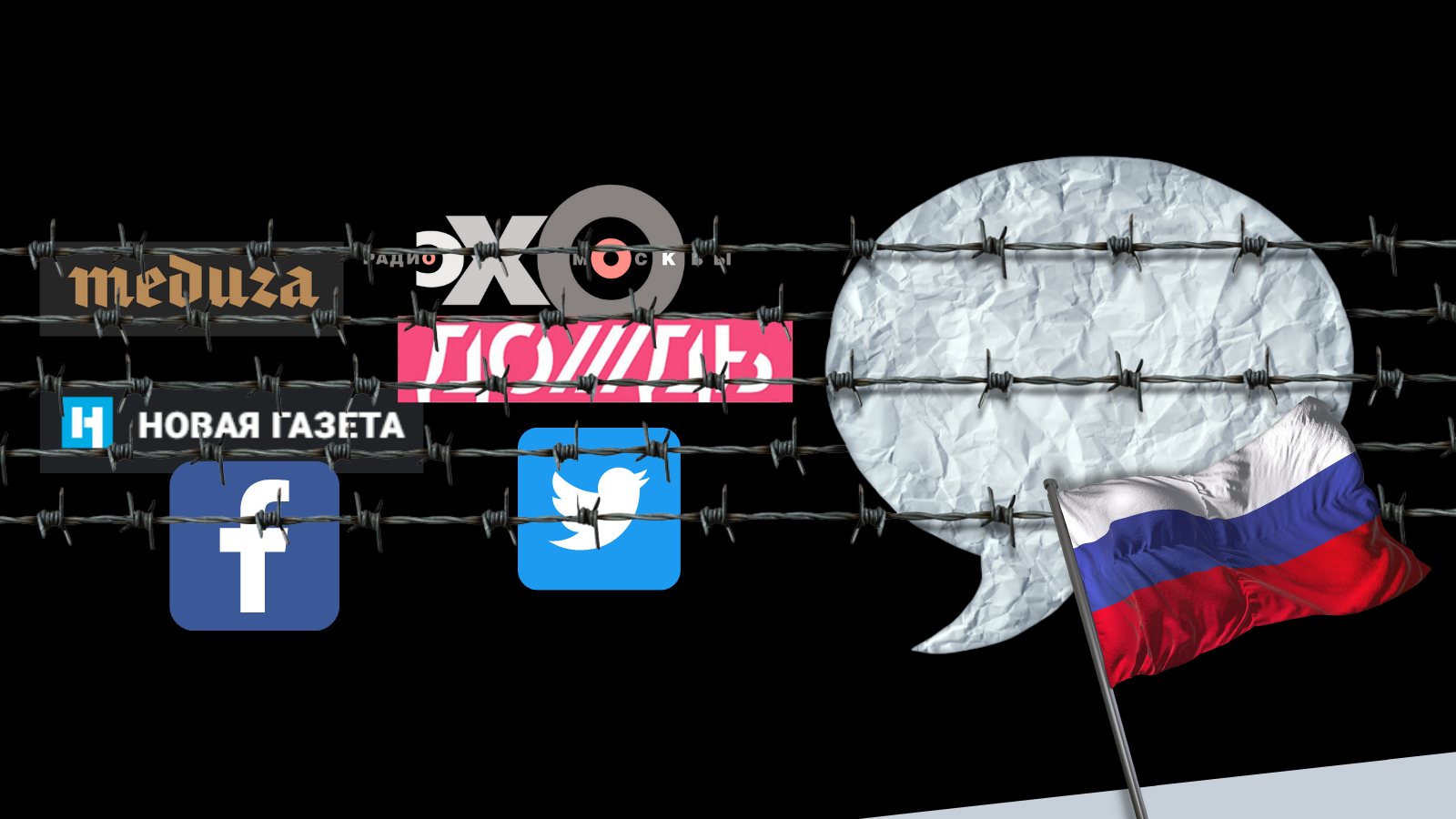

One year of draconic censorship laws has terrified Russian society. Multi-year prison sentences and thousands of court cases induce fear and self-censorship. Practically all independent journalists have either left Russia or closed down.

This article is the fourth update in a series tracking and analysing the changing Russian information space following the censorship laws introduced in March 2022. See our earlier updates below from 5 March, 8 March, and 26 March 2022 [here].

One year ago, shortly after Russia launched its full-scale aggression against Ukraine, the Russian parliament quickly approved wide-ranging censorship in the form of a new paragraph added to the Criminal Code. Article 207.3 stipulated up to 15 years in prison for ‘spreading false information about Russian armed forces or officials’. The new article’s creation followed instructions from 24 February, the first day of the full-scale war, when the Russian media supervisory agency Roskomnadzor ordered media outlets in Russia to only report official information from state bodies.

We covered the initial consequences during 2022: the closure of media outlets, banned platforms, journalist departures, court cases, etc. See other articles here and here.

New additions to the Russian Criminal Code and the Administrative Code have complemented the repressive legal framework. They include the Criminal Code’s new article 275.1 defining punishments for ‘confidential cooperation’ with foreigners, now equated to treason, and new article 20.3.3 in the Administrative Code stipulating an administrative fine of up to 100,000 roubles for individuals spreading false information, an amount roughly equal to two average monthly salaries in Russia.

One year later: from already bad to a lot worse

Even before the 24 February invasion, the situation for independent media in Russia was very difficult with labels like ‘foreign agent’ or ‘undesirable organisation’ slapped on normal, professional journalists and publications. Poorly investigated attacks and even killings of high-profile journalists had contributed further to a chilling atmosphere.

After 12 month, things have become even worse. For example:

- The media landscape inside Russia is fundamentally changed and now dominated by Kremlin orders. See our weekly disinformation reviews here.

- Independent Russian media and journalists have left Russia in large numbers.

- Strong NGOs like Memorial and the Sakharov Centre have been closed or liquidated by court order. Previously, they documented instances of repression, human rights and freedom of expression.

- The court system has moved into repression mode. Now more than 6,000 cases, administrative and criminal, of ‘discrediting the armed forces’ have been launched, according to the independent observer Mediazona.

- The more prominent a person is – say, with many followers on social media – the more severe the sentence. Punishments range from economic fines to correctional labour to multi-year sentences in prison. See a list of recent cases here.

- The bar has been set low for ‘spreading false information’ about the Russian army, officials or security forces, as the examples below demonstrate.

Anything that is not from ‘official sources’ like the Russian Ministry of Defence, state outlets or wire services is increasingly considered ‘false’. According to Mediazona, alleged falsehoods can include criticism such as calling Russian troops in Ukraine ‘occupiers’, criticising the bombing of civilian targets, or merely reporting on atrocities committed by Russian forces in places like Bucha. A re-post or a comment on social media is enough to land a sentence or a hefty administrative fine. If repeated, an offender can be charged as a criminal.

Recent examples illustrating the trend

At the end of 2022, opposition politician Ilya Yashin received an eight-and-a-half-year prison sentence for posting information about Russian forces killing civilians in Bucha. In July 2022, local Moscow politician Alexei Gorinov was sentenced to seven years in prison in a similar case.

Authorities charged opposition politician and activist Vladimir Kara-Murza with state treason (up to 24 years in prison) for criticising Russian forces for bombing schools and hospitals in Ukraine during a speech last year in Arizona.

On 1 March, Dmitry Ivanov, a student at Moscow State University (MGU), was sentenced to eight-and-a-half years in prison for running a website called ‘Protesting MGU’ where people could post personal remarks about the war. The Telegram site has some 9,000 subscribers.

On 6 March, Ruslan Gannev, a web developer from Tatarstan, was sentenced to ten months of correctional labour and fined 10% of his salary for two posts on Russian social media questioning the withdrawal of Russian forces from Kyiv and the number of combat losses.

Also on 6 March, Andrey Novashov, a journalist from Kuzbass in Siberia, was sentenced to eight months of correctional labour for posts on Russian social media calling the Russian forces in Ukraine ‘occupiers’ and criticising the targeting of civilian infrastructure.

On 3 March, Igor Korotkov, from a village in the Krasnodar region, was fined 800,000 roubles for posting a link on WhatsApp to the Navalny Live channel streamed on YouTube, one of the few non-Russian / Chine platforms still allowed in Russia. The fine is equal to roughly two years average income in such a rural area.

Rulings also include in absentia court cases. Recent examples

On 6 February: Well-known journalist and blogger Veronika Belotserkovskaya, residing in France, was sentenced in absentia to nine years in prison. The case against her began in March last year when she posted criticism about Russian forces murdering children, bombing a maternity hospital in Mariupol, and murdering civilians in Bucha.

On 1 February, a Moscow court sentenced journalist Alexander Nevzorov in absentia to eight years for discrediting the armed forces.

And there are more than 6,000 cases in the pipeline as of early March 2023…

Update 26 March 2022

The trend of blocking websites has been greatly accelerated. There are two general trends: blocking services and a complete censorship of information content. Blockings of foreign media outlets now affect BBC, Deutsche Welle, RFE/RL, and Euronews TV channel websites, while CNN, ABC and CBS news have been suspended, together with less well known independent channels. Independent journalists are fleeing the country, given that not adhering to the censorship rules can bring a prison sentence. This includes anyone who opposes the so-called ‘special military operation’ or disseminates “fakes” about actions by the Russian military forces or the state bodies outside the territory of the Russian Federation.

The Russian State Duma approved legislation with fines and jail sentences (for certain types of actions up to 15 years) those who publish “knowingly false information” about actions abroad by Russian government agencies which were done “in the interests of Russia and its citizens, international peace and security”. This complements the law from of 4 March on similar punishment regarding false information about the Russian Army.

Sergei Klokov, an employee of the Moscow Interior Ministry’s Main Directorate became the first person known to be arrested for allegedly disseminating “false” information about the Russian military, which he allegedly did in a telephone conversation. There has been no court permission to wiretap Klokov’s conversations.

A ban was issued on the operations of the Meta company’s platforms in Russia, on the grounds of “extremist activities”. The ban concerns the two most popular social networks in Russia: Facebook and Instagram. It does not apply to the messenger WhatsApp.

Google and its platform YouTube remain, but it is likely not to be for long. On 18 March, Russia’s media regulator, Roskomnadzor, demanded that Google stop the spread of videos on its YouTube platform, which it says are “threatening Russian citizens.”

More VPNs are blocked. Russians used to download an average of 16,000 VPN apps per day. On 9 March, they downloaded 700,000. This was before the decision to block Instagram. In 10 days between 24 February and 5 March, the top 10 VPN apps on the App Store and on Google Play saw more than 4.6 million new downloads.

On 4 March, the Russian parliament adopted unanimously and at record speed a law “on responsibility for fakes about the Russian forces”. It foresees draconian punishment for anyone who dares voice criticism or questions Putin’s war in Ukraine. As of 5 March, the law now also covers criticism of Rosgvardija, Putin’s 300.000 strong militia guard, part of which is now operating in the occupied areas in Ukraine.

Citizens charged under this law face fines running up in 1,5 million of Rubles (10.000 – 13.000 EUR depending on exchange rate) and up to 15 years in prison or labor camp for criticising the war or spreading what authorities consider “false” information, i.e. anything that deviates from the official government line.

The law applies to all residents of Russia, both Russian and foreign nationals.

In the Russian content, such legislation paves the way for almost unlimited censorship and self-censorship. It is certain to further muzzle dissent in Russia and constitutes the harshest crackdown on media and social media in post-Soviet Russia.

Off the air, off the net, dissolved by the Gazprom shareholder

The trend of the law is already seen. The removal of web content of the last free radio station, the renowned and balanced Radio Echo Moscow, was executed under threats of hefty punishment. The radio had been taken off airwaves days earlier by the Russian state media agency Roskomnadzor. The majority stake owner Gazprom Media (yes, that state gas company Gazprom) decided to shut down the company in what is obviously a political liquidation.

We can no longer link to the statement of protest by Echo Moscow Editor-in-Chief Alexei Venediktov.

Update (8 March): Adding insult to injury: the FM-frequency of now-closed-and-dissolved Radio Echo Moscow will be taken over by radio Sputnik of the RT / Russia Today. It will take effect from 9 March. Imagine, Radio Echo Moscow which opened on 22 August 1990 and a year later, August 1991 managed to keep transmitting despite attempts to block it made by the Soviet hard-line coup makers.

Update (26 March): Venediktov reported on 22 March that in front of his door a pig’s head was left together with a sticker with the Ukrainian emblem and the word ‘Judensau’.

Self-censorship

Novaya Gazeta, the crusading newspaper that won the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize along with its editor-in-chief Dmitry Muratov, has published a message informing readers that it will now remove all materials related to the war in Ukraine from its website and social media accounts to protect its staff. In earlier publications, Novaya Gazeta reported on the war and didn’t shy away from using names like invasion, war, bombing, casualties, etc. Novaya Gazeta’s website was still accessible from Russia as of 4 March.

Social media platforms, pollsters, foreign media – ordinary people; get them all!

For years, social media platforms and news aggregators with just a few thousand regular users have been legally considered to be media in Russia. Thus, following the logic of the law, platforms will have to police what is posted and remove content or face punishment.

Opinion pollsters publishing studies where questions can be seen as suggesting criticism of the war in Ukraine also fall within the scope of the law.

It remains to be seen how this will affect foreign media and journalists operating in Russia. In principle, the law has no limitations and will therefore apply to anybody on the territory of Russia or within its jurisdiction. There are already examples of foreign correspondents, such as Le Monde’s limiting their posting on Twitter when inside Russia or the BBC suspending work of their journalists inside Russia.

Update (07 March): Leading independent media outlets operating in Russia, both Russian and foreign, have been blocked, either partially or entirely, or have withdrawn staff or reduced / discontinued operations in view of the new law.

In a parallel move on 4 and 5 March, Roskomnadzor blocked Facebook and later also Twitter for users in Russia. This will affect millions of users as Facebook is dominant platform in Russia. Twitter is also popular among business communities.

At the same time, on 4 March, Putin just signed another law “on foreigners violating the fundamental rights of Russians”. A virtual spree of laws and regulations in all directions seem to fly from the Kremlin.

All these draconic laws sends a clear signal: no dissent about Putin’s unprovoked and unjustified war in Ukraine will be tolerated.

A brief question…

Few may now dare ask the question to Putin and the Kremlin: – why has a supposedly, “limited operation to protect Donbas” led to the most harsh censorship and limit of personal freedoms in the history of modern Russian?

Why? According to the poll by (Soviet-era, still Kremlin-affiliated) pollster VTsIOM* from 4 March 70% of Russians support Putin and 74% approve of his work. Why can’t they be allowed to express this joy on Facebook?

…and the Russian Constitution…?

Let us end with quoting the Russian Constitution Article 29

Everyone shall have the right to freedom of thought and speech.

Propaganda or campaigning inciting social, racial, national or religious hatred and strife is impermissible. The propaganda of social, racial, national, religious or language superiority is forbidden.

No one may be coerced into expressing one’s views and convictions or into renouncing them.

Everyone shall have the right to seek, get, transfer, produce and disseminate information by any lawful means. The list of information constituting the state secret shall be established by the federal law.

The freedom of the mass media shall be guaranteed. Censorship shall be prohibited.

See the statement by EU High Representative Borrell here.

*VTsIOM originate from the research department of the former USSR Ministry of Social Affairs.