The growing sophistication of Russia’s disinformation campaigns in Africa demand greater vigilance from tech companies, internet watchdog groups, and governments. An Interview with Dr. Shelby Grossman.[1]

By the Africa Center for Strategic Studies — February 18, 2020 —

In October 2019, Facebook removed dozens of inauthentic coordinated accounts operating in eight African countries that had been engaged in a long-term disinformation and influence campaign aimed at promoting Russian interests. The accounts were linked to Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch with long-standing ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin who has been indicted for interfering in U.S. elections. Prigozhin also heads up the infamous Wagner Group, a private security contractor that has deployed former Russian military personnel into African conflict zones, including Libya, the Central African Republic, Mozambique, and Mali.

The deactivated accounts, which targeted Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Libya, Madagascar, Mozambique, and Sudan, provide insights into the opaque realm of Russian disinformation campaigns in Africa.

Dr. Shelby Grossman, a research scholar at the Stanford Internet Observatory, led the team that worked with Facebook to identify and analyze Russian-linked disinformation campaigns in Africa. Such campaigns are a growing concern for African countries where information systems are often vulnerable to manipulation, due, in part, to the prevalence of misinformation—the mistaken, rather than intentional, sharing of inaccurate information. The Africa Center talked to Dr. Grossman about her research and its implications for recognizing and combatting disinformation in Africa.

What do we know about the inauthentic content posted on Facebook and Instagram?

All the pages removed by Facebook were pages linked to “a firm” tied to Yevgeny Prigozhin. We know that these pages are linked to Prigozhin for two reasons. The first is a document that we received from the Dossier Center, a Russian investigative organization founded by Mikhail Khodorkovsky, a Russian oligarch who fell out of favor with Putin, that showed Prigozhin’s employees boasting about having created Facebook pages targeting Libya. The second source was Facebook. When we brought the Libya pages to Facebook, they said they had been investigating dozens of other pages that had the same upstream actor, i.e. Prigozhin, and asked if we wanted to investigate them jointly.

“The content consisted of a lot of ‘cheerleading’ for whomever was currently in office.”

The Facebook and Instagram content we analyzed was typically supportive of the ruling party in whatever country the page or account was targeting. Generally, the content consisted of a lot of “cheerleading” for whomever was currently in office. The most straightforward examples were the Mozambique pages, created in September 2019, just a month in advance of Mozambique’s elections. The pages existed exclusively to promote the Frelimo ruling party. There would be posts of incumbent President Filipe Nyusi holding a rally with a really big crowd and other similar content.

It was not always that straightforward, however. An example of a slightly more complicated set of pages were those targeting Libya. These pages fell into one of two categories. One category was pages supportive of Khalifa Haftar, the Russian-backed rebel commander trying to undermine the UN-recognized government and seize Tripoli. Wagner Group mercenaries are fighting alongside Haftar’s forces right now, so those pages shared Haftar cheerleading content with messages suggesting that Haftar would bring security and peace to Libya.

Interestingly, there was another set of Libya pages that can be described as Muammar Gaddafi nostalgia pages with posts saying, essentially, “Weren’t things so great under Muammar Gaddafi?” That would be 90 percent of the posts, and then 10 percent of the posts would be supportive of one of his sons, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, who is seen as a possible presidential candidate and is also under indictment by the International Criminal Court for war crimes. These two sets of pages are in line with what we know about Russia’s interests in Libya: they are actively supporting both of these individuals (Haftar and Saif al-Islam Gaddafi). This is interesting because the two could become rivals for power, though some people think that the Russians are trying to bring the two together.

What impact do you think this content has had?

The million-dollar question is the effect these pages had. What we can say is that people engaged with this content. Almost across the board, the pages had high levels of engagement. The 73 inauthentic pages we analyzed posted 48,000 times, received more than 9.7 million interactions, and were liked by over 1.7 million accounts. This suggests that the content the campaigns created resonated with people who, in turn, responded to it.

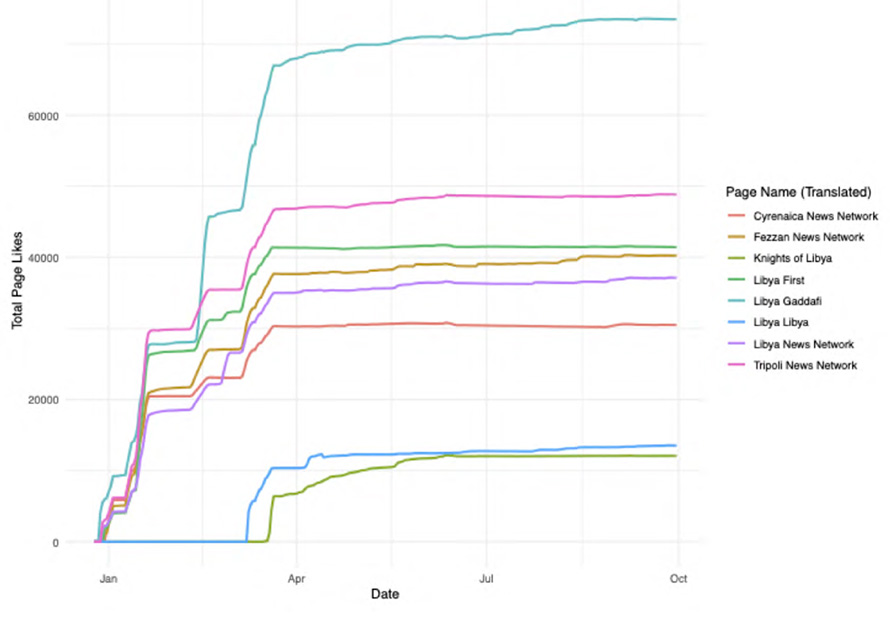

“The simultaneous spikes and plateaus in ‘likes’ across clusters of inauthentic pages targeting specific countries … suggest that something else might have been going on.”

We also saw people responding skeptically to this inauthentic content. In the example of the Muammar Gaddafi nostalgia pages, a lot of the posts would be along the lines of “Remember when things were so great under Gaddafi? There was better healthcare, etc.,” and people would sometimes respond by saying things like, “Who are you?” “Did you actually live under Gaddafi? Because if you did you would never say this kind of nonsense.” So people to some extent did respond skeptically to the inauthentic content posted on these pages. And we saw this pushback in other countries. There was one example of a fake news story posted on the Mozambique pages that alleged that the opposition party had entered into a contractual agreement to allow the Chinese government to dispose of nuclear waste in Mozambique, which obviously doesn’t make any sense—how can an opposition party sign a contract with another government?—and people responded by saying “fake news!!” in Portuguese. One person responded, “I think your tin hat is wound too tightly around your head; this can’t be true.” So, while the modal reaction was somewhat supportive of the pages, there were definitely some examples of people responding skeptically.

It is hard to say whether all the accounts that “liked” and engaged with these pages were authentic accounts. We observed a pattern that we’re calling “the staircase plot” of “likes” occurring at similar times across these clusters of inauthentic pages, which is suspicious. If just one page showed this spike, I might think it was the result of the page running an advertisement—and we do know that the pages did run ads. Facebook reports that these pages spent $77,000 on ads. But what makes us more suspicious is the simultaneous spikes and plateaus in “likes” across clusters of inauthentic pages targeting specific countries, which suggest that something else might have been going on.

Were the inauthentic pages and their content a series of ad hoc experiments, or were they part of a broader coordinated disinformation strategy in Africa?

Russia has specific interests in Africa. Prigozhin has mining interests and has close ties to Putin, so it’s not a huge leap of the imagination to think that Putin is interested in these mining investments as well. A possible explanation in CAR and other countries could be that Russia was trying to get mining rights by supporting the current politicians in power. One of the CAR pages was very strange. It was a page for a Malagasy mining company that had controversial ties to a Russian firm. It was actually an empty page with no posts, and Facebook didn’t give us any information about why they included it in the pages they provided to us. We just know that because they included it, it’s linked to Prigozhin, which suggests that mining interests may have been part of these disinformation operations.

“Prigozhin seems to be trying to pay more local actors to create the content.”

I think the other thing here is the sequencing. These pages started up in 2018, and that was right after Facebook and Twitter finished removing the bulk of the Internet Research Agency’s accounts in the United States. (The Internet Research Agency is a pro-Kremlin propaganda operation indicted by the United States on charges of attempting to influence the 2016 U.S. elections.) So the sequencing is that a lot of their activities in the United States get shut down and then they’re starting up in Africa.

I think it is possible that they were testing out strategies while pursuing their African interests. In countries we analyzed, Prigozhin seems to be testing a “franchising” strategy.

Dr Shelby Grossman – Photo DE

The Internet Research Agency’s strategies that targeted the United States in 2016 were all run out of St. Petersburg, and a lot of the tweets were written in very bad English, whereas that was not a problem with the Africa operation we analyzed. Prigozhin seems to be trying to pay more local actors to create the content.

This franchising is important because:

- It’s creating more locally authentic content that resonates with users

- The quality of the writing is better

- It makes it so much harder to detect these disinformation campaigns

If you care about Russian disinformation and want to use Facebook’s Page Transparency feature, this is no longer a foolproof tool because it is being gamed by franchising. After we finished analyzing all 12 of the Libya pages that we knew were linked to Prigozhin, one of the things we tried to do was see if we could have figured out on our own that they were tied to Russia without having the Dossier Center documents. We came to the conclusion that we would not have been able to. That’s how good they are. It took this leaked internal document for us to be able to figure it out. So it’s not clear how any ordinary Libyan citizen would have been suspicious because even if they did take advantage of Facebook’s Page Transparency feature, they would see that the administrators were in Egypt, which is not that surprising because a lot of Libyans live in Egypt.

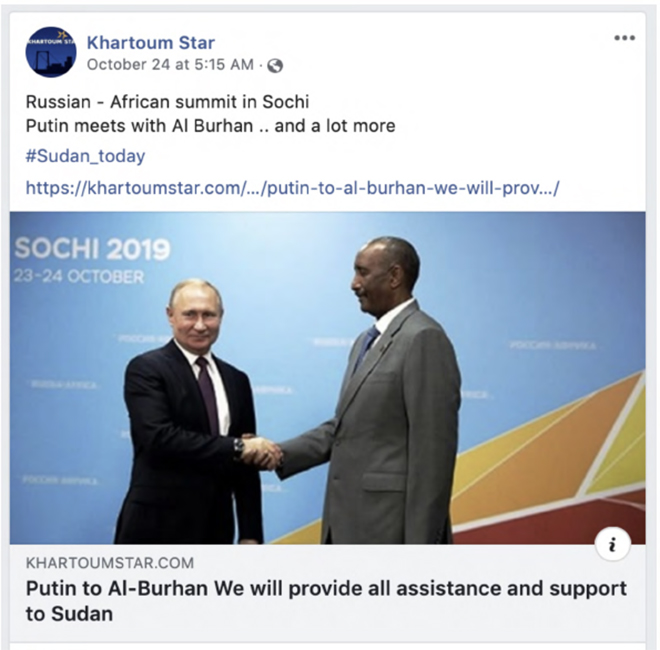

Another intriguing strategy was that the Sudan pages did not appear to post biased content. I could not find many fake or biased stories on the Sudan newspapers’ pages. The Sudan pages were created while President Omar al-Bashir was still in power, and they continued to be active during and after the coup. They are still up and actively publishing content today on websites (their Facebook pages were taken down), and the tone never really changed. One would think if they had an agenda to push, they would have been promoting the Transitional Military Council or posting content that was anti-protest. But they didn’t, and so that was kind of baffling, and we’re still not 100 percent sure what is happening. One theory is that Prigozhin is investing long term in these outlets so that they will be seen as credible media organizations so that when an event happens that Prigozhin/Russia really care about or want to polarize society around, they’ll go in strong with a really biased slant.

How is Facebook working to deter future Russian disinformation campaigns, and is Prigozhin countering their efforts?

When we brought Facebook the inauthentic Libya pages, they were already investigating other pages that they had linked to Prigozhin, which I think is important to note. They were being proactive about looking into these pages, even in a context where there isn’t that much political pressure being put on them. Facebook has a huge team that’s working to detect disinformation. The Facebook Blog publishes a post every other week describing one of their takedowns that is attributed to a state actor. Facebook is also trying to collaborate with civil society groups like our team at the Stanford Internet Observatory who are focusing on certain parts of the world and alerting them to things that look suspicious.

A news outlet linked to Prigozhin called RIA FAN posted an entire article responding to our report point by point. They actually included a screenshot of a table from our report listing the admins for all the Libya pages and argued that Facebook is trying to censor “African” voices because they just don’t want Egyptians managing Facebook pages. We thought this was really interesting because they were leaning into this franchising strategy of not having the pages managed in Russia. So I saw this as evidence that this was a very intentional strategy.

One of the trends your team illustrates is that the disinformation campaigns were typically created following or leading up to a specific event such as after the bread price protests in Sudan or in the weeks before Haftar’s Tripoli offensive in Libya. How might social media users recognize these campaigns as they are unfolding in the future?

It’s really hard to recognize these campaigns as they’re unfolding in real time, and if disinformation researchers can’t identify something without an internal document, it’s not reasonable to expect ordinary people to figure it out. There are online literacy programs being developed, and there are some things individuals can do such as looking at the URLs that social media accounts are sharing. If those URLs are just Russia Today or Sputnik content or other disreputable news outlets, that’s pretty suspicious. But usually it’s not that obvious.“The CAR pages were managed by admins in Madagascar and CAR.

The Sudan pages were managed by people in Sudan, Russia, and Germany.”

Facebook’s Page Transparency feature is something that people should definitely still utilize because, even though it might not tell you exactly who’s running the page, it will be revealing if it’s not what you expect. The locations shown by the Page Transparency tool may be different than the administrators’ self-declared locations. They are determined by Facebook, using whatever information it has to try to really figure out where people are located, even if they have tried to conceal their location. The Page Transparency information for the Libya pages had a plurality of admins in Egypt, and for a variety of reasons, we suspected it was managed by an Egyptian digital marketing firm. The CAR pages were managed by admins in Madagascar and the CAR. The Sudan pages were managed by people in Sudan, Russia, and Germany.

Another useful tool that’s free is the CrowdTangle plugin on the Google Chrome internet browser. If you’re on a website that looks weird, you can click the CrowdTangle button on your browser and it will tell you all the social media accounts that are referring to the website. So if CrowdTangle shows that, hypothetically, a Vladimir Putin fan group on Facebook is linking to it, that can give you a sense that something weird is going on with the site.

What more can African governments, firms, and ordinary users do to better guard against future disinformation campaigns?

It’s unclear what incentives African governments in targeted countries have to address these disinformation campaigns given that a lot of the disinformation, at least that we found, was supporting them. It seemed likely that many of them actually knew what was going on. There have been articles that came out in the wake of our report that have argued that African governments should pass more disinformation laws. However, given that they’re often benefiting from these campaigns, it’s not really clear that these laws would be meaningful. In general, when citizens are consuming information on social media, they should think about how that content is trying to make them feel, and if it feels like your emotions are being manipulated, then it’s a good idea to be suspicious.

One of the things that’s been illuminating in following Libya is the level and extent of foreign meddling. There are at least six countries that are actively meddling in Libyan politics in a very serious way, and many of them are conducting online meddling. Ordinary Libyans are extremely conscious of this, and in general, they’re incredibly against foreign involvement. I think that shows that when people are aware of foreign disinformation campaigns, it makes them angry that other countries are meddling and spreading disinformation. Khadeja Ramali, the world’s leading Libya social media expert, makes the point that the social media sphere in Libya is so overrun by foreign disinformation actors that it actually crowds out local voices. Libyans don’t like that, but it’s hard to fight individually. Consequently, it’s absolutely critical that tech companies step up their vigilance in fighting disinformation.

[1] Shelby Grossman is a research scholar at the Stanford Internet Observatory. She taught Democratic Erosion at the master’s and undergraduate level at the University of Memphis, where she worked as an assistant professor from 2017-2019. Shelby’s research focuses on disinformation in sub-Saharan Africa, along with the political economy of development. She holds a Ph.D. in political science from Harvard. Her work has been published in Comparative Political Studies, PS: Political Science & Politics, World Development, and World Politics.

Additional Resources

- Kimberly Marten, “Russia’s Back in Africa: Is the Cold War Returning?” The Washington Quarterly, Volume 42, December 20, 2019.

- Shelby Grossman, Daniel Bush, and Renée DiResta, “Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations in Africa,” Stanford Internet Observatory, October 29, 2019.

- Christopher Ajulo, “Africa’s Misinformation Struggles,” The Republic, Volume 3, No. 3, September 6, 2019.

- Joseph Siegle, “Recommended U.S. Response to Russian Activities in Africa,” Russian Strategic Intentions White Paper, NSI, May 9, 2019.

- Joseph Siegle, “Managing Volatility with the Expanded Access to Information in Fragile States,” Development in the Information Age, February 2016.

- Stephen Livingston, “Africa’s Evolving Infosystems: A Pathway to Security and Stability,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 2, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 31, 2011.

More on: Disinformation — Russia

See also: Des campagnes de désinformation russes ciblent l’Afrique: Entretien avec le Dr Shelby Grossman (2 mars 2020).