In December 1917, the soldiers of the National Guard’s 42nd Division were all in France, waiting for training in the trench warfare that defined World War I in Europe.

In December 1917, the soldiers of the National Guard’s 42nd Division were all in France, waiting for training in the trench warfare that defined World War I in Europe.

The division's 27,000 troops had started moving to France in October from Camp Albert Mills on Long Island. The last elements of the 26-state division — the 168th Infantry Regiment from Iowa — had reached France at the end of November.

Review of the 42nd Infantry Division at Camp Mills, N.Y.

The 42nd Division had been formed by taking National Guard units from 26 states and combining them into a division that stretched across the country, “like a rainbow,” in the words of the division chief of staff, Army Col. Douglas MacArthur.

The largest elements were four regiments from Ohio, Iowa, Alabama and New York, which were organized in two brigades of two regiments and supporting units.

The New York National Guard's 69th Infantry Regiment, renowned as the “Fighting 69th” had been renamed the 165th Infantry Regiment.

Christmas in France

By Christmas, the division's elements were located in a number of villages northeast of the city of Chaumont, about 190 miles east of Paris. The men had hiked there from Vaucouleurs, where they had originally been deposited by train.

The 165th Infantry Regiment celebrated Christmas in the village of Grand. Father Francis Duffy, the regiment's famous chaplain, celebrated a joint American-French mass on Christmas Eve.

According to Army Sgt. Joyce Kilmer, a poet and editor, “the regimental colors were in the chancel, flanked by the tricolor. The 69th was present, and some French soldier-violinists. A choir of French women sang hymns in their own language, the American soldiers sang a few in English, and French and American [voices] joined in the universal Latin of ‘Venite, Adoremus Dominum.”

On Christmas Day the men ate turkey, chicken, carrots, cranberries, mashed potatoes, bread pudding, nuts, figs and coffee. The Army, wrote Cpl. Martin Hogan “was a first-rate caterer.”

The Iowa National Guard’s 168th Infantry Regiment hosted 400 French children at a Christmas celebration in the village of Rimaucourt. Two American soldiers dressed as Santa Claus gave presents to the French children and a French band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The children received dolls, horns and balloons, recalled Lt. Hugh S. Thompson in his book, “Trench Knives and Mustard Gas.”

The 168th didn't eat as well as the 165th on Christmas day, according to Thompson. “Scrawny turkeys and a few nuts were added to the usual rough menu,” he recalled.

The Ohio National Guard’s 166th Infantry Regiment was reviewed by Army Gen. John J. Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force, just before Christmas. On Christmas they enjoyed music from the regimental band and a good meal.

The ‘Valley Forge Hike’

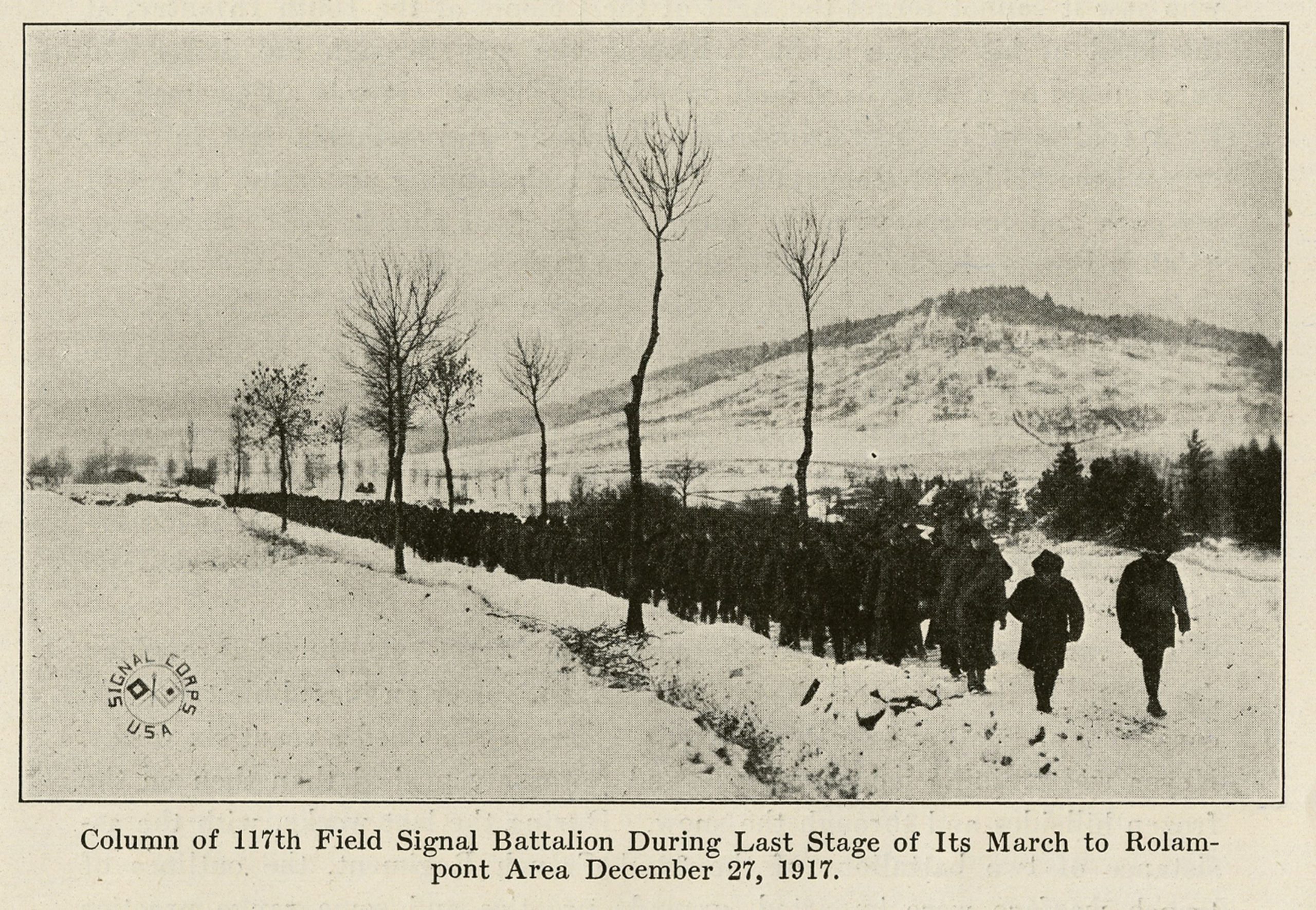

While Christmas 1917 was a good one for most of the Rainbow Division, the next week went down in the division's memory as the “Valley Forge Hike.”

It was 30-40 miles from where the division's troops had celebrated Christmas to the town of Rolampont, where the Army's Seventh Training Area had been established.

Today, you can drive the route in an hour. In 1917 it took the soldiers four days to get there.

The march was miserable, according to the 1919 book, “The Story of the Rainbow Division.”

The soldiers had “scarcely any shoes except what they had on their feet, there was no surplus supply to speak of. Some of the men had no overcoats.”

They walked into a mountain snowstorm. In some places the snow was 3-4 feet deep. Soldiers’ shoes wore out. Some marched almost barefoot, and there were bloody trails in the snow.

Thompson recalled that the men in his unit were issued hobnailed boots: the soles were held by heavy nails. The problem, he said, was that the nails got cold and the men's feet froze.

Soldiers with the Missouri National Guard’s 117th Field Signal Battalion in Dec. 1917 during the “Valley Forge Hike

Bleak expanses of icy geography appeared and vanished in monotonous fields between villages,” he said. “Legs ached, pack straps cut into shoulders unmercifully. Men fell out, exhausted.”

At night, the men huddled in the barns and haylofts of the French villages to keep warm.

The mule- and horse-drawn supply wagons got stuck on the icy roads and men had to move their best animals from wagon to wagon to get them unstuck, Duffy recalled.

Stretched Thin

For three days, the men in the 165th Infantry Regiment's 3rd Battalion had no food, Kilmer said, and when rations caught up to the men they got coffee and a bacon sandwich, or a raw potato and bread.

“The hike made Napoleon's retreat from Moscow look like a Fifth Avenue parade,” one New York officer remembered later.

“The men plowed over the hills and [through] the snow, enduring hardships which are not pleasant to remember,” wrote Reppy Alison, the author of a book about the 1st Battalion, 166th Infantry Regiment.

Medics reported cases of mumps and pneumonia as the temperatures dropped below zero. Hundreds of men fell out — at least 700, including 200 of the New Yorkers — but most made it to Rolampont.

As the 165th Infantry Regiment arrived, the regimental band struck up “In the Good Old Summer Time.”

By New Year’s Day the division's elements had all arrived in Rolampont, and along with a new year they got a new commander.

Army Maj. Gen. William A. Mann, the former head of the Militia Bureau, the equivalent of today's Chief of today’s National Guard Bureau, had taken command of the division at Camp Mills.

But, at age 63, Mann couldn't meet the physical standards for officers established by Pershing.

Mann was replaced by 55-year-old Army Brig. Gen. Charles T. Menoher.

As 1918 began, Menoher and the soldiers of the Rainbow Division began gearing up to go into the trenches. After completing a demanding training regimen led by the British and French armies, the division would spend 264 days in combat before the war ended on Nov. 11, 1918.

Army Features Veterans World War I Centennial

About the US 42nd “Rainbow’ Division

When the US declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker ordered the creation of an Infantry Division of National Guard troops that would “cover the United States.” Calling in the country’s best trained militia, four infantry regiments of 3,670 officers and men each were brought together at Camp Mills, Long Island. They were joined by National Guard support units from twenty-six other states and the District of Columbia, bringing the new 42ndDivision to a total strength of about 27,000 officers and men.

It sailed from New York in October, 1917 and was twinned for training with French infantry regiments in the Lunéville sector of Lorraine, before becoming the third among US Divisions to engage the Germans.

Supreme Commander Foch asked General Pershing on June 21, 1918 to move the Division to the Champagne to help the French in the battle that stopped the German “Peace Offensive” towards Paris on July 15, 1918. The entire 42nd Division took the brunt of the assault with the 167th (Alabama) Infantry Regiment and the 109th French Regiment in the center. General Gouraud recognized its excellent fighting qualities and said that the “Rainbow” put a new spirit into France.

Four days later Foch ordered an Allied offensive to the northeast from Château-Thierry. The 167th (Alabama), with its sister regiment, the 168th (Iowa) on its right flank, led the “Rainbow” Division thrust and fought a great battle here at Croix Rouge Farm on July 26, 1918. The Germans were forced to retreat to prepared positions along the Ourcq River.

The 167th (Alabama) and the 168th (Iowa) followed them for 10 km to the west bank of the Ourcq on July 27 where they were joined by the full “Rainbow” Division. It attacked across the river on July 28. The 165th (New York), initially fighting at Meurcy Farm just south of the present Oise-Aisne Cemetery, was brigaded with the 166th (Ohio) Regiment. All of the “Rainbow” took part in the battles on the hills east of the river. All were blessed and inspired by the senior Chaplain, Father Francis Duffy. The poet Joyce Kilmer was killed in this fighting and posthumously named Poet Laureate of the United States. Major William T. “Wild Bill” Donovan, who later rose to global distinction as head of the US Office of Strategic Services in World War II, precursor of the CIA, led a New York battalion in the battle. After four days of hard fighting by both sides, a massive German retreat began on August 2, 1918. Casualties in this operation for the “Rainbow” were 184 officers and 5,469 men.

On September 11, 1918, the resupplied 42ndDivision took part in the All-American attack at St. Mihiel. After night marches to the jump off position, the Division delivered the main blow in the direction of the heights overlooking the Madine River.

It then moved 100 km to join 1st US Army attacking in the Argonne. That operation fell three weeks behind the schedule agreed to by Generalissimo Foch and General Pershing; its October 4, 1918 attack was pushed back and the Americans retreated for the first time in the war.

On October 11, the “Rainbow” replaced the exhausted 1st US Infantry Division, “the Big Red One”, the most famous US Division, which had been unable to penetrate the Kriemhilde Stellung of the Hindenburg Line at the Côte de Châtillon. The “Rainbow” attacked the hill on October 14, 1918. Under constant fire in the rain and mud the 1st Battalion of the 168th(Iowa) gained sufficient high ground to cover the assault of the 3rd Battalion of the 167th(Alabama) on October 16, 1918. The two regiments closed on the German position at the same time and shared equal honors for the victory.

Moving towards Sedan, all of the 42nd Division joined in the general attack until the war ended on November 11, 1918. It entered Germany and served in the Army of Occupation until April 25, 1919. Returning to Camp Meritt, New Jersey, the “Rainbow” dispatched all units to home states for discharge.

Source : American War Memorials Overseas Inc.

The Battle of Croix Rouge Farm (July 25-26, 1917)

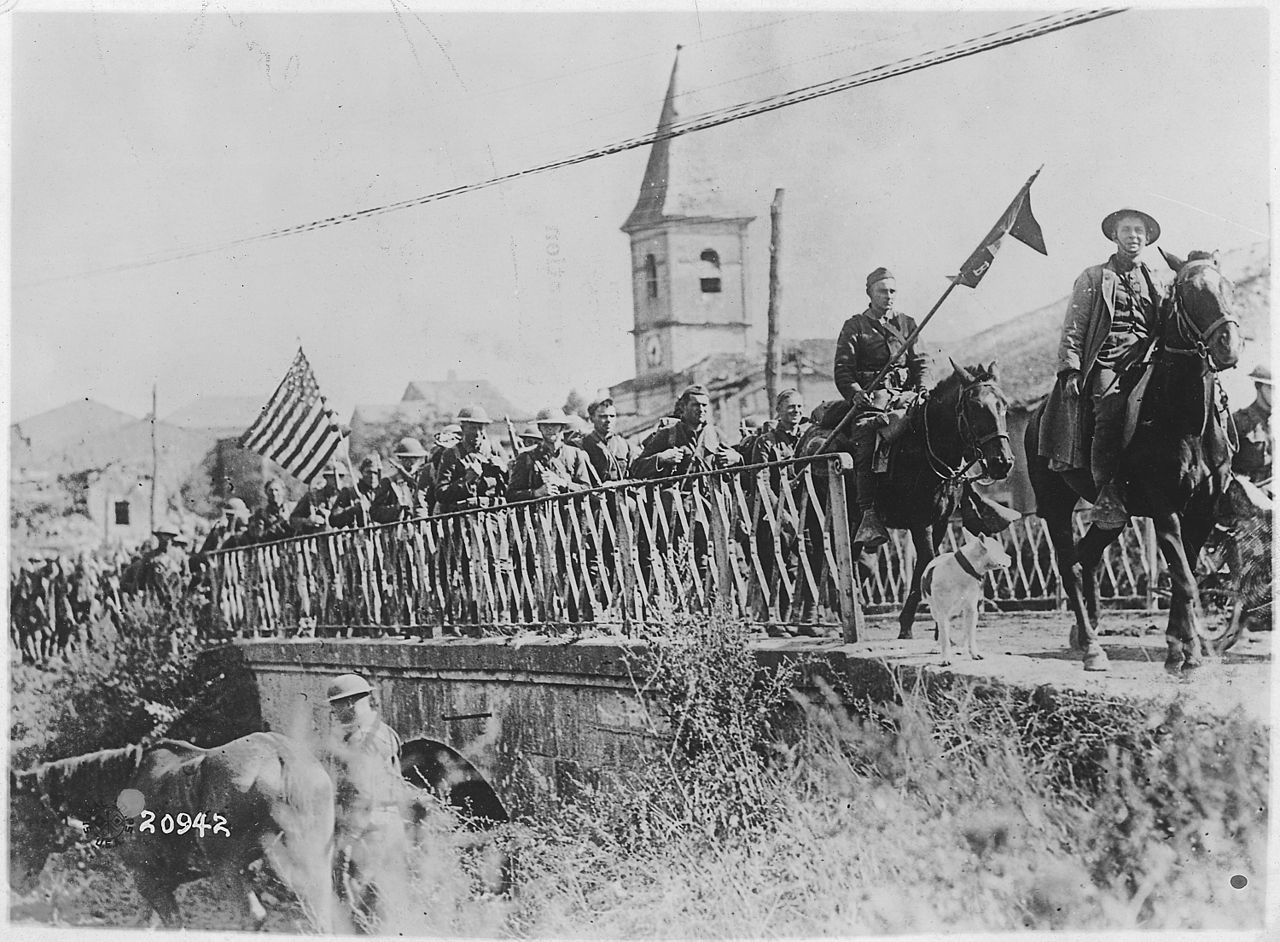

42nd Rainbow Division in Fère-en-Tardenois, Aisne (France)

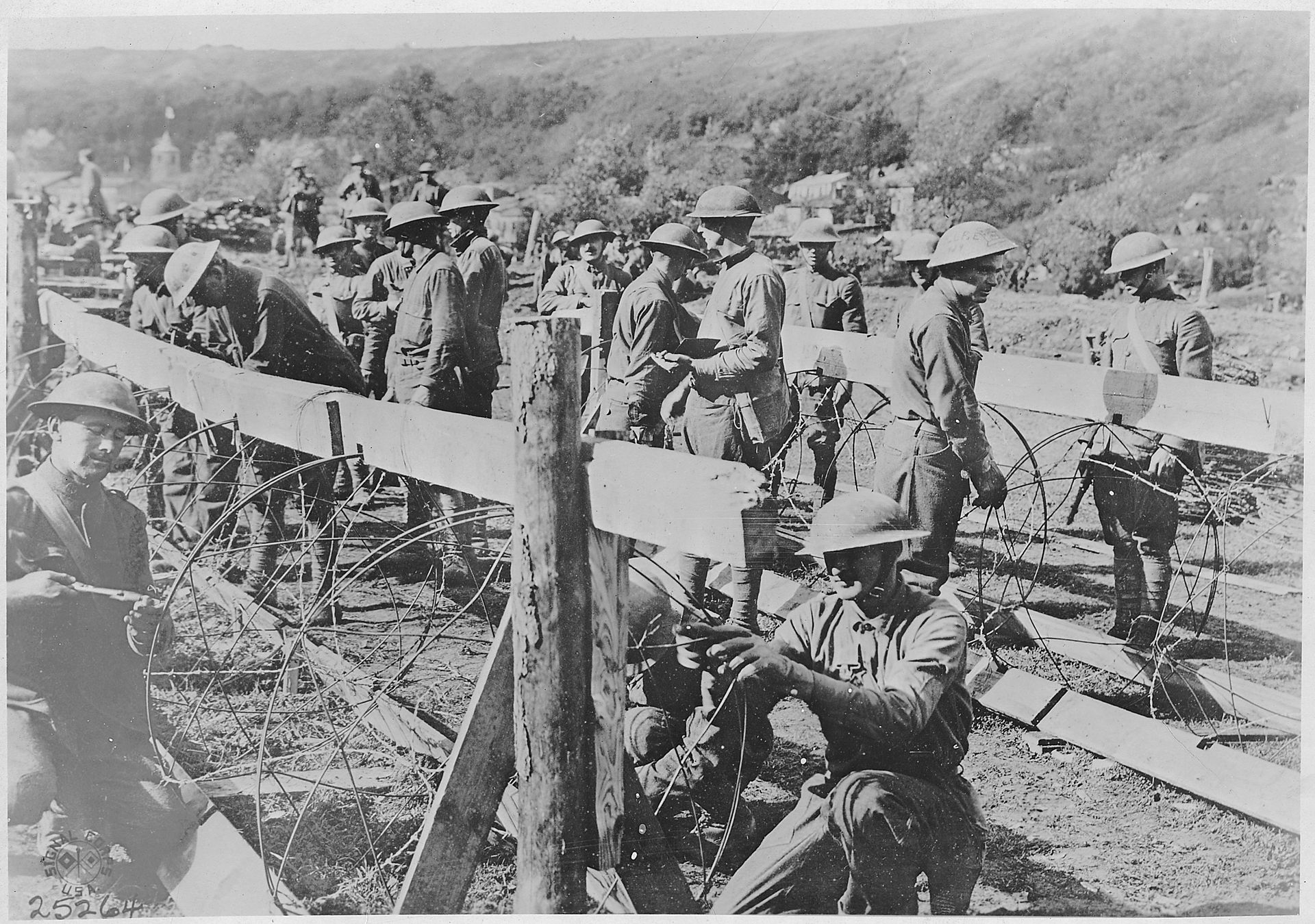

At dusk on July 25th, the “Rainbow” Division’s 167th (Alabama) Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel William Preston Screws, replaced elements of the 26th “Yankee” Division on a skirmish line in the woods west of the Croix Rouge farm. Germans opposing were from the 4th Guards, an elite unit, and the 10th Landwehr Division. Artillery fired intermittently into the

On the cold and raining morning of July 26th, the “Rainbow’s” 168th (

Attacking without artillery support, the 1st Battalion of “Alabama” moved into the open at 4:50 in the afternoon from the woods west of here. Elements of C and D Companies attacked through A and B Companies, quickly losing mortars and machine guns, and were nearly wiped out in open field fighting lasting little more than fifteen minutes. The day appeared lost as the field grew quiet for more than an hour. A second effort by remnants of D Company and C Company was organized, about 100 men. Successful from the beginning, the force charged across the open field but lost more than half of its people. Ruthlessly using rifles, bayonets and rifle butts it drove the Germans from the field.

At about the same time the 3rd Battalion filtered through the woods south and southwest of here. On coming out of the trees, platoon after platoon was stopped by German fire from the farmhouse and prepared positions in the open field and along the road to the south. The 3rd Battalion appeared doomed until a thrown together platoon of infantrymen and machine gunners from Companies K and I, supported by only a single mortar, charged the farmhouse from the south. They were joined by another mixed force from K and L Companies that had taken out German machine gunners east of the farmhouse and road. With both 3rd Battalion forces attacking under heavy fire, the remains of a platoon from Company L, along with two men left from Company F of the 168th Infantry, swept forward to reach this place by eight o’clock in the evening. German artillery continued throughout the night.

Dawn on July 27th found the battlefield covered with German and American dead and wounded, but the Germans troops had withdrawn. During the night Aid Stations had treated more than 1,100 wounded, including Germans. Among 162

Source : American War Memorials Overseas Inc.

See also:

La SPA 75 est centenaire ! par SIRPA Air (2016-07-08)

Verdun 2015 : La légende de la « tranchée des baïonnettes » par Domenico Morano (2016-07-28)

Remembering, Honoring First Americans to Fight, Die in World War I by Jim Garamone (2016-10-19)

In 1917, ‘Rainbow Division’ Celebrated Christmas in France by Eric Durr (2017-12-19)

African-American Troops Fought to Fight in World War I By Army Col. Richard Goldenberg (2018-02-01)

WWI Centennial: German Spring Offensive of 1918 Threatens Paris by David Vergun (2018-04-06)