Censorship, conveyor-belt sentencing, gangster attacks, economic suffocation and waterfalls of disinfo flooding public discourse: revanchist, militant nationalism is drowning the Russian information space.

By EUvsDisinfo | March 15, 2024 —

Table of Contents

The last remaining pretence of media freedom in Russia is quickly falling away. The suspicious death of Alexey Navalny has left Russian leader Vladimir Putin with few if any viable domestic opponents, and he seems to relish his strongman image. His state-of-the-nation address on 29 February set a new tone in the Kremlin’s information operations: that of a dictator seemingly confident that no one would dare oppose him.

For Russians who believe that their country should be free, open, and prosperous, the current moment is bleak. As one mourner for Navalny said, ‘I don’t have any vision of the future.’

At EUvsDisinfo, we tracked the debits in Russia’s media freedom account in the earlier editions of this series, Vols. 1 – 4. Below is our fifth update listing the ways that Russian authorities have manipulated the domestic information space and tightened their grip on civil society further since our last report in March 2023. So far, we see no reasons for optimism.

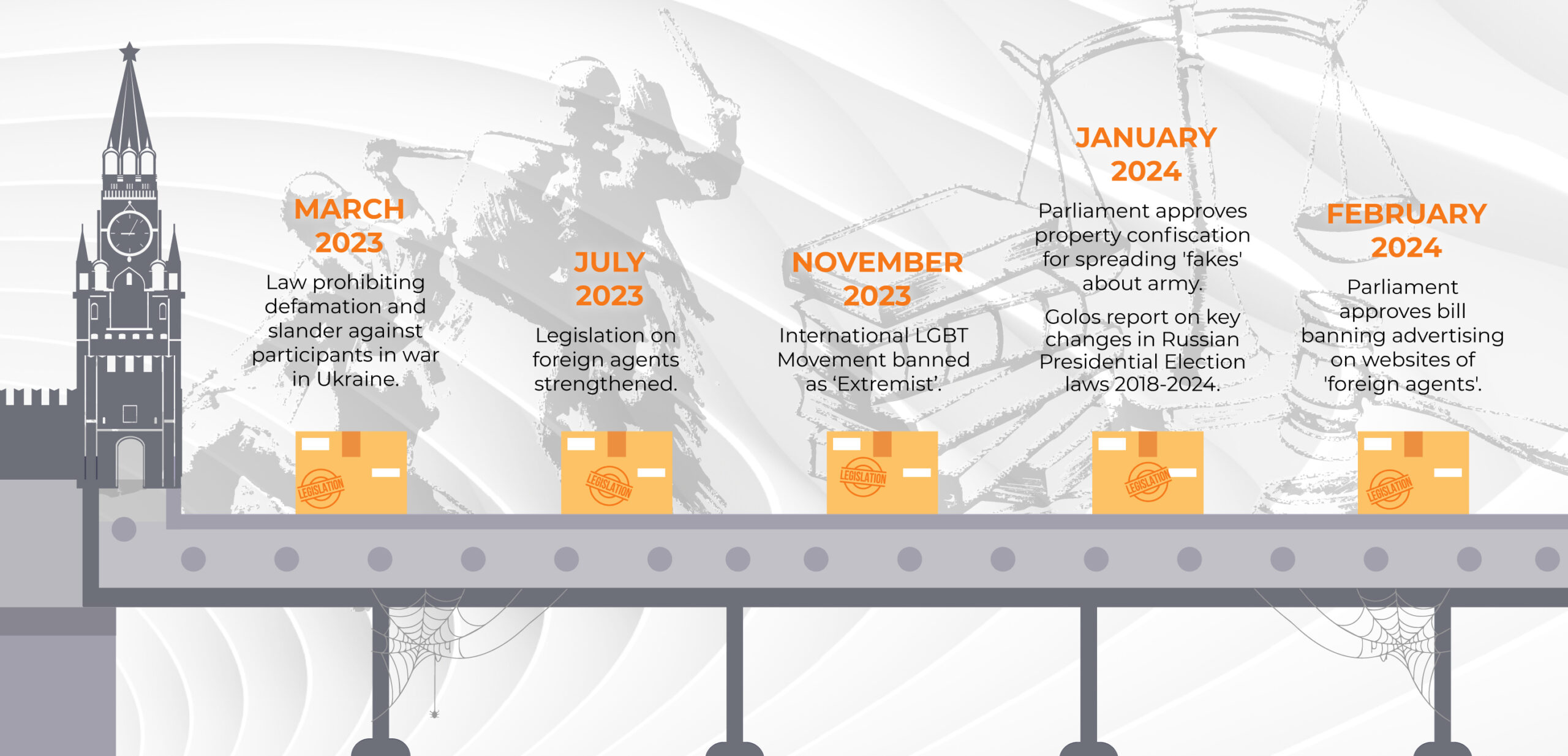

Re-introduce censorship

First, some essential background. The day that Russia launched its full-scale war against Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the Russian media supervisor agency Roskomnadzor ordered all media outlets in Russia to only report information officially distributed by state bodies when reporting on the invasion. Shortly afterwards, the Russian parliament added new censorship laws to the Criminal Code. In particular, Article 207.3 mandated up to 15 years in prison for ‘spreading false information about Russian armed forces or officials’. The courts have used this instrument numerous times, convicting countless people in order to send a clear signal to society: either support the Kremlin, remain silent, or go to jail.

Other new laws included article 275.1 in the Criminal Code that mandated punishments for ‘confidential cooperation’ with foreigners that is now equated with treason, and article 20.3.3 in the Administrative Code imposing a fine of up to 100,000 roubles – equal to two-three months of an average Russian’s salary – for ‘spreading false information’.

But the new laws were only the beginning, as authorities have wasted no time in enforcing them with increasing gusto. Let’s picked up from where we left off, in March 2023.

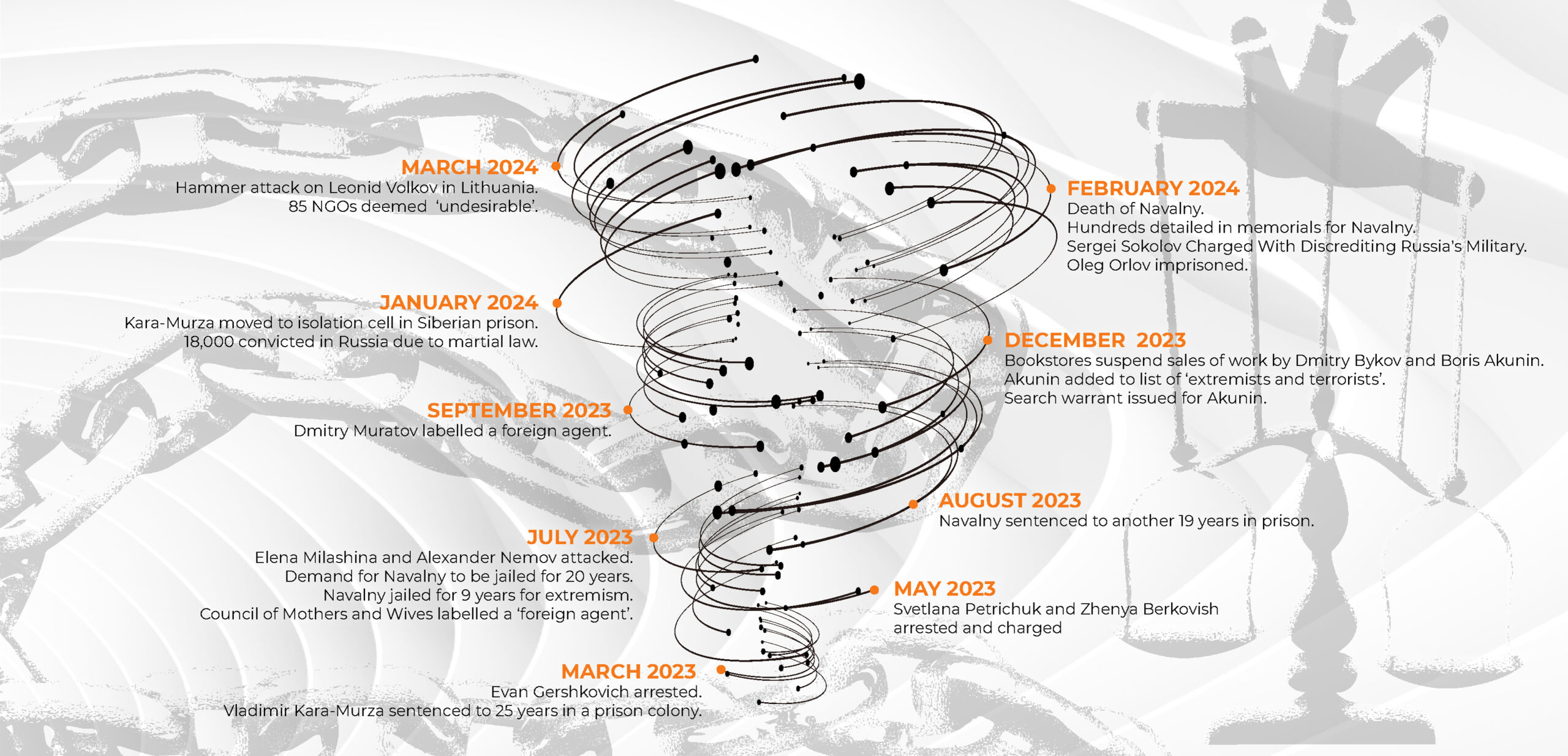

Control the externals

On 30 March 2023, Russian authorities arrested Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich and accused him of espionage. The linked article notes that the arrest was the first time since the Cold War that authorities had brought a spy case against a foreign reporter. The Kremlin likely hopes to use Gershkovich as a pawn in a future swap for Russian convicts in the US, using a mafioso-style practice known as ‘hostage diplomacy’.

A long list of other foreign media correspondents have been targeted in different ways: losing their press accreditation, being denied entry into Russia, facing angry harassment from ‘local citizens unhappy with their reporting’, or by having their Russian staff members labelled ‘foreign agents’.

Silence the opposition: criminalising dissent

Then in April 2023, a Russian court sentenced journalist and opposition activist leader Vladimir Kara-Murza to 25 years in a prison colony after convicting him of high treason and other politically motivated changes. A winner of the 2022 Václav Havel Human Rights Prize, Kara-Murza was arrested on 11 April 2022 shortly after returning to Russia in the wake of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The noose tightened further in May 2023 when Russian authorities deemed ‘undesirable’ 85 NGOs. Being called ‘undesirable’ has serious consequences. For example, you can lose the financial means for self-support, and others could be considered criminals for even having contact with you. In essence, it is one step away from being branded a traitor.

Throughout the year, authorities also expanded the practice of labelling any conceivably objectionable domestic entities or individuals as ‘foreign agents’. The Justice Ministry updates its list of such agents every Friday, making for a continuous conveyer belt of internal vilification.

One particular spiteful instance of repression concerned Russian playwright Svetlana Petrichuk and theatre director Zhenya Berkovish. Together, the duo staged a play entitled, ‘Finist, the Brave Falcon’, about Russian women recruited by ISIS. The play used the testimonies of Russian women to convey an anti-extremist message. Following its debut in Moscow in 2021, the play was honoured with glowing reviews and two national Golden Mask awards.

But on 5 May 2023, Petrichuk and Berkovish were arrested and charged with ‘justifying terrorism’. The evidence largely rests on a single document submitted by Russian nationalists accusing the women of advocating a mixture of ‘ISIS ideology’ and ‘radical feminism’. Authorities have since held the pair in pre-trial isolation, extended several times. Their anti-war poems have probably attracted the Kremlin’s negative attention.

‘We know where you are’

Also in May 2023, the US-based head of the Free Russia Foundation, Natalia Arno, said that she was likely poisoned during a trip to Prague early that month. Fortunately, her symptoms have since partly subsided. But the event is suspicious given that the Kremlin has a well-documented history of using poisonings and other methods to assassinate its perceived adversaries.

In August, German prosecutors announced that they were investigating the possible attempted murder of yet another Russian journalist, Elena Kostyuchenko. She fell ill in October 2022 while on a train from Munich to Berlin but believes that she might have been poisoned. She was one of three exiled Russian journalists at the time to feel poisoning symptoms. If the Kremlin is behind such attacks, then these gangster tactics are likely designed to scare Russian journalists or political activists into silence.

July 2023 saw a small avalanche of attacks and restrictions. Early in the month, unknown assailants attacked Russian journalist Elena Milashina and attorney Alexander Nemov as they were on their way to attending the sentencing of a human rights activists in Chechnya. The assaults on them occurred in the context of other violent attacks on journalists documenting developments in the North Caucasus, especially Chechnya. The message is loud and clear.

Get one last use out of Navalny

Then on 20 July, Russian state prosecutors demanded that Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny serve an additional 20 years in a penal colony for treason. One ridiculous charge accused him of misbehaving in prison. Just a few days later, a court sentenced a Navalny supporter for nine years in prison for being part of a so-called ‘extremist community’. Even his defence lawyers were arrested multiple times for doing their jobs. Authorities apparently want all to know that there is no space for dissent. In August, a Russian court mostly fulfilled a July request from Russian prosecutors by giving Navalny another 19 years in prison.

Not even the spouses and mothers of Russian soldiers could escape repression. On 28 July, the Council of Mothers and Wives, an organisation that advocated for the interests of mobilised and conscripted men in the Russian army, abandoned its activities after Russian authorities labelled it a ‘foreign agent’.

The conveyor belt of administrative decisions

Meanwhile, the ‘foreign agent’-labelling conveyer belt continued to move. This time, the victim was Nobel Prize-winning journalist Dmitry Muratov, editor of the Novaya Gazeta newspaper. Novaya Gazeta, a famed independent outlet established in 1993, closed up in Russia in March 2022 and moved many of its operations to Latvia as a new legal entity. Muratov resigned and remains in Russia, along with other members of the editorial staff.

At the end of the 2023, two instances of censorship stood out. First, the Russian publishing house AST suspended the sales of books by Russian journalist, writer, and poet Dmitry Bykov and the popular Russian-Georgian writer Boris Akunin for their views against the war in Ukraine. The Kremlin then added Akunin to the state financial overseer Rosfinmonitoring’s list of ‘extremists and terrorists’. Russia’s Investigative Committee even issued a search warrant for Akunin, who now lives in the United Kingdom, on charges of ‘justifying terrorism’ and spreading ‘fake news’.

Crueller, pettier, deadlier, faster

In the new year of 2024, Russian authorities continued to turn the screws on whatever is left of the Russian opposition, often in cruel and petty ways. On 30 January, news emerged that Russian authorities had used an alleged trivial infraction as justification for moving Vladimir Kara-Murza to a new Siberian penal colony. There, they placed him in solitary confinement for four months.

Then in March 2024, a hearing for Petrichuk and Berkovish extended their detentions again until April, with no trial date in sight.

Stories from February to the present were dominated by Alexey Navalny’s sudden death in a Siberian prison, and the arrests of hundreds who paid homage to his memory at makeshift memorials across Russia. The Kremlin did not pause, however, in its attempts to make life harder for civil society leaders. On 20 February, Rosfinmonitoring added Evgeniya Chirikova, a Russian environmental activist, and Ivan Tyutrin, an opposition politician, to its list of extremists and terrorists. Both serve on the Standing Committee of the Free Russia Forum, and both live outside of Russia.

Get the prominent voices…

Others live inside Russia and could not escape arrest. Dmitry Muratov’s replacement as chief editor, Sergei Sokolov, was himself arrested on 29 February 2024 and charged with discrediting Russia’s military. Around the same time, a Russian court sentenced Oleg Orlov to two and a half years in prison for denouncing the war in Ukraine. Orlov is a president of the Memorial human rights organisation, famous since the Soviet Union years and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2022.

…and suffocate their financing

In March 2024, the Russian parliament rubberstamped a law making it criminal to place advertising with ‘foreign agents’. Accepting advertising and violating the law twice in a year can give the ‘foreign agent’ two years in prison. This is a new way of suffocating the practical operation of many independent outlets or media initiatives at the democratic, grass-root level. To a large extent, these initiatives have survived thanks to smaller-scale crowdfunding which has gone under the radar so far. But no longer.

This was illustrated in early March 2024 when journalist Katerina Gordeeva announced that she had been obliged to suspend her YouTube show, ‘Tell Gordeeva’, in large measure because the Kremlin’s designation of her as a ‘foreign agent’ made it impossible for the show to attract advertising.

In addition, the Russian Interior Ministry added British journalist Tom Rogan on its wanted list after Rosfinmonitoring slapped him on its list of extremists and terrorists.

Part of a larger picture of repression

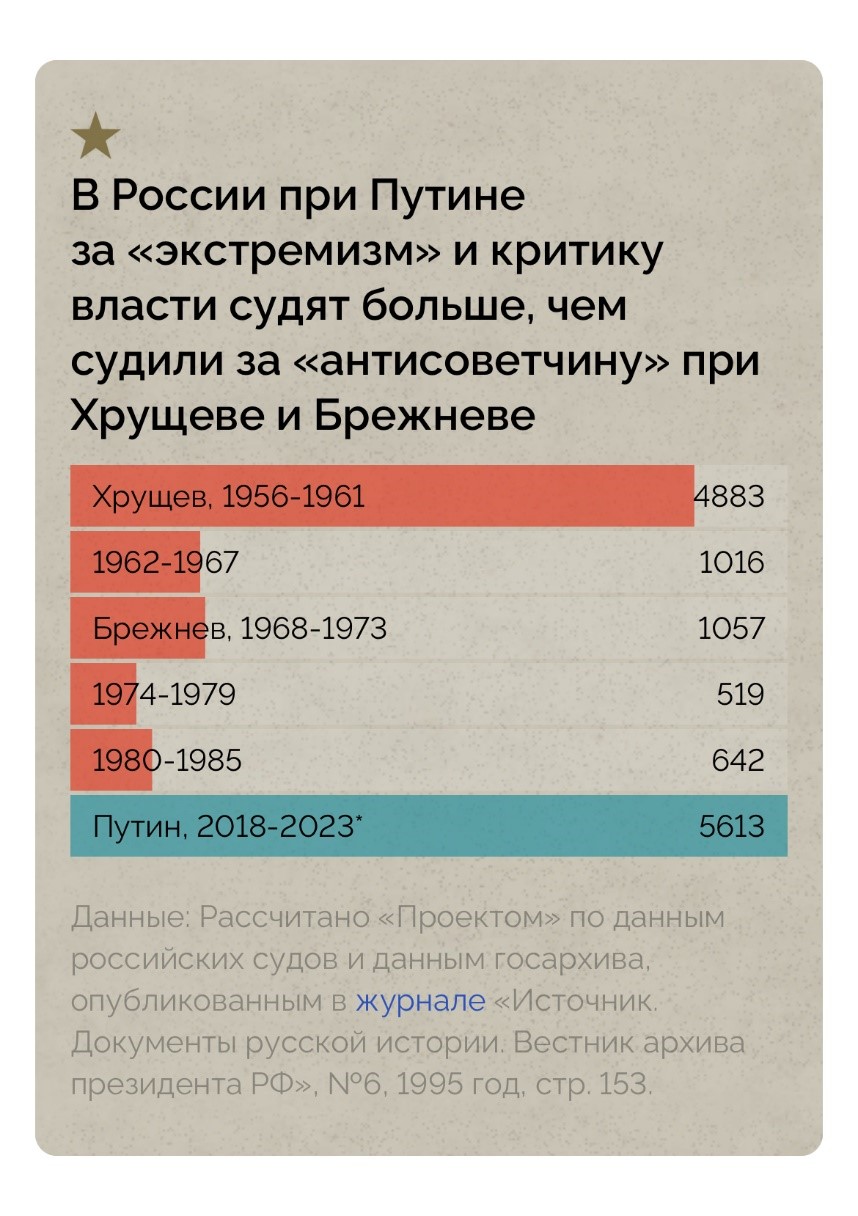

We will end with a recent paper released by Project, an independent Russian investigative journalism outlet, in the aftermath of Navalny’s death. The paper makes for sobering reading. Project found that over the past six years, Russian authorities have directly repressed at least 116,000 people. This figure exceeds corresponding numbers repressed in the USSR under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, and it is likely an undercount.

Putin’s institutionalised wrath against all his real or perceived enemies, increasingly magnified by rising bureaucratic efficiencies, continues to get crueller, pettier, deadlier, faster.