Looking down from history’s summit at the challenges and crises of the past, it is human nature to see them as less complicated and dangerous than those we face today. The threats have either subsided or disappeared, the standoffs have long since been resolved, and hindsight has shown us all the answers—most of them, anyway—to the questions that were so vexing back in the day.

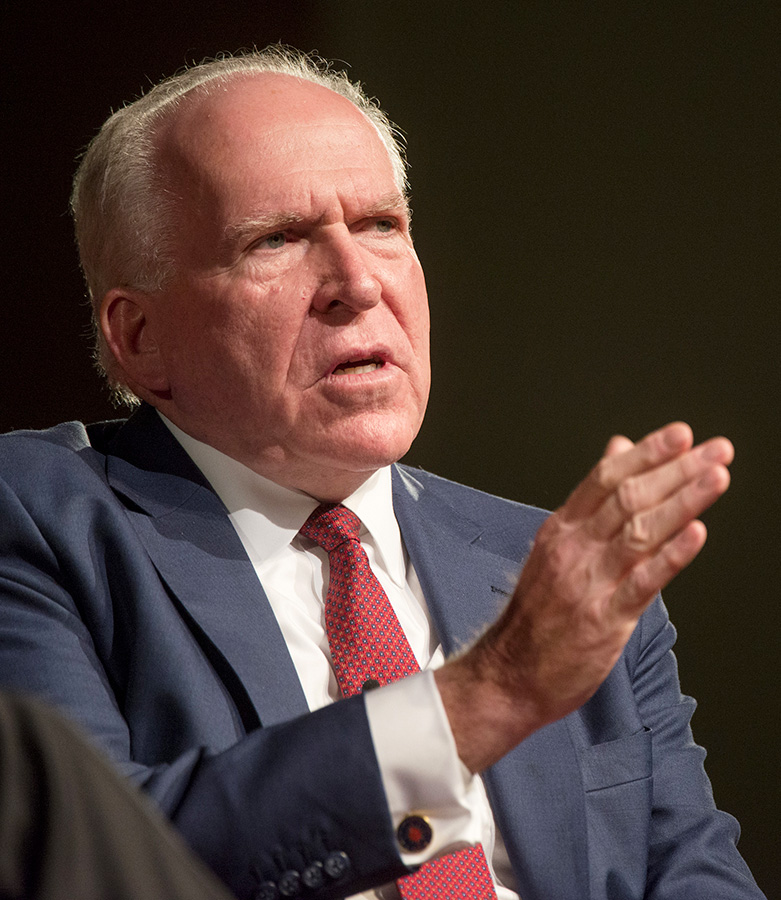

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery CIA Director John O. Brennan at the President’s Daily Brief Public Release, LBJ Library in Austin, Texas. September 16, 2015. Source : CIA.

Good afternoon everyone. Having spent some wonderful years as a student at UT—and still a proud Longhorn—it is my very great pleasure to be back in Austin.

I want to thank Mark [Updegrove, LBJ Library Director] and his excellent staff for hosting today’s event. When President Johnson dedicated this library, he said, “It is all here… the story of our time with the bark off.”

You can’t get much further below the bark than Top Secret intelligence reports, so I think President Johnson would approve of today’s proceedings.

I also want to thank my good friend and one of our Nation’s greatest patriots, Admiral William McRaven, Chancellor of the University of Texas System, for speaking later this afternoon on the importance of intelligence. It is highly appropriate for Bill to help celebrate the history of the President’s Daily Brief because, for a number of years, the operations he commanded helped fill the book with some of its very best intelligence.

I also want to offer my gratitude to two outstanding Agency leaders—former CIA Director Porter Goss and former Deputy Director of Central Intelligence Bobby Inman—for lending their insights and expertise to the panel discussion coming up next. And finally, I want to thank my good friend General James Clapper, the Director of National Intelligence and a veteran officer who knows this business inside-out, for rounding out today’s conference with his closing remarks.

President Johnson made a point of keeping most of his speeches to a 400-word limit. I may be dangerously close to hitting it already, but I plan to hold the podium for a while so I can offer a few words on today’s release and the enduring challenge of preserving our national security.

On his first full day in office, President Obama called on the heads of executive departments and agencies to build an unprecedented level of openness in our government. He made it known that giving the American people a clear picture of the work done on their behalf—consistent with common sense and the legitimate requirements of national security—would be a touchstone of this administration.

In light of this new approach—and pursuant to an Executive Order outlining new classification and declassification guidelines—CIA information management officers worked with their counterparts at the National Security Council and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to start the review and declassification of PDBs that were more than 40 years old.

And today, for the first time ever, the Central Intelligence Agency is releasing en masse declassified copies of the President’s Daily Brief and its predecessor publications—some 2,500 documents from the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

This is just the beginning—some 2,000 additional declassified PDB documents from the Nixon and Ford administrations will be released next year, and the process will continue.

The PDB is among the most highly classified and sensitive documents in all of government. It represents the Intelligence Community’s daily dialog with the President in addressing challenges and seizing opportunities related to our national security. And for students of history, the declassified briefs will lend insight into why a President chooses one path over another when it comes to statecraft.

John O. Brennan – Photo Jay Godwin

And today, for the first time ever, the Central Intelligence Agency is releasing en masse declassified copies of the President’s Daily Brief and its predecessor publications—some 2,500 documents from the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. This is just the beginning—some 2,000 additional declassified PDB documents from the Nixon and Ford administrations will be released next year, and the process will continue.

The PDB is among the most highly classified and sensitive documents in all of government. It represents the Intelligence Community’s daily dialog with the President in addressing challenges and seizing opportunities related to our national security. And for students of history, the declassified briefs will lend insight into why a President chooses one path over another when it comes to statecraft.

The release of these documents affirms that the world’s greatest democracy does not keep secrets merely for secrecy’s sake. Whenever we can shed light on the work of our government without harming national security, we will do so.

* * *

The story of the PDB begins more than fifty years ago, at President Kennedy’s weekend retreat near the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. It was June 17th, 1961, and an aide had just arrived from Washington carrying a Top Secret document. The President sat down to read it next to the swimming pool, perched on the edge of the diving board.

The document was seven pages long and printed on short, square blocks of paper, with spiral binding along the top. Inside were two maps, a few notes, and 14 intelligence briefs, most no more than two sentences in length, on topics ranging from Laos to Cuba to Khrushchev. After reading the document, the President sent word that he was pleased with the contents. An aide contacted the officers at CIA who had written it and said: “So far, so good.”

This was the very first issue of what would become the PDB. The publication quickly became a must-read for President Kennedy, and it set in motion a routine for delivering intelligence to the Oval Office that has been at the heart of CIA’s mission ever since.

The idea behind the PDB was developed quickly, in a matter of days, to meet a very specific need. Since taking office, President Kennedy had been frustrated with the way intelligence was being delivered to him. The reports he was receiving were long, dense, and abstract, and they would come in haphazardly throughout the day, making it hard for him and his staff to keep up. The result was that much of what he was being given each day went unread, and the President was making policy decisions without the benefit of the intelligence our government had collected for him.

A few months into the President’s term, after he was caught off guard by several developments on the intelligence front, his brother Robert Kennedy lit into the President’s staff. CIA soon got a call from the White House, demanding that the Agency find a better way to keep the President informed.

In consultation with the President’s advisors, a team of Agency officers decided to produce a daily digest—delivered each morning to the White House—that would summarize in a few pages all the intelligence that deserved the President’s attention. They called it the “Pickle,” short for the President’s Intelligence Checklist, the forerunner of the PDB. The idea was so successful that it has endured, in various forms, under ten Presidents, and today it is such a vital part of how the White House operates that one can hardly imagine the modern presidency without it.

Throughout its history, the PDB has helped the President confront the gravest subjects a Commander-in-Chief can face, issues like terrorism and famine and war. But as you will see in the documents we are releasing today, the PDB’s history includes more than coverage of crisis and conflict. In today’s collection you will find offbeat items like Russian reaction to a performance by the New York City Ballet, and commentary on a decision by the New York Yankees to fire Yogi Berra. You will encounter a host of lively characters, such as a political leader in Latin America described as “a high living, fifth-of-Scotch a day man.” You will also find occasional doses of humor, a fair number of off-color remarks, and an entire issue comprising little more than a poem.

Today the PDB is the most abundantly staffed, most deeply sourced daily information service in the world. It provides the President with a wealth of insight and analysis on virtually every issue on his foreign-policy agenda. But when the idea of the PDB was first conceived, the plans were not nearly so ambitious.

The document was envisioned as more of a straightforward news bulletin, summarizing the latest developments, rather than a font of in-depth analysis. There was very little in the way of rigorous forecasting in the early years. Whole disciplines that are integral to the intelligence business, such as covert action, were largely left out. Director John McCone, who was appointed by President Kennedy, thought that some subjects were too sensitive to be included in the document, so he would relay them to the President in person instead, a practice that has continued over the years.

Nevertheless, today’s PDB in many respects is unrecognizable from what it was in the Kennedy and Johnson years. One of the clearest differences is the writing style. Back then, articles were full of colorful language and personal asides that would never make it past a PDB editor today.

Consider this report from 1967 about the harassment of diplomats in China: “A mob kept [one ambassador] in his car for 10 hours, causing him to ruin both his clothing and the upholstery.”

Or this assessment of a fact-finding team that was sent to Yemen in 1967: “[The team] left yesterday with more haste than dignity,” after “six gunfire-ridden days spent mostly locked in hotel rooms and presumably under the beds.”

It gets more colorful, but I think you have the idea. Having been a PDB Briefer myself in the 1990s, I can assure you that the commentary was at times quite sporty and eyebrow-raising when the PDB was discussed in the Oval Office.

Beyond the writing style, the PDB has evolved in countless ways since those early years. It has grown in length and sophistication, adding features like graphics and imagery. It is more comprehensive now, and the analysis is far more rigorous. And perhaps most importantly, it has gone from a document written by just a handful of people at CIA, to one produced by officers representing an array of organizations, specialties, and disciplines.

Many of the changes have been driven by technology, and by the possibilities afforded by our expanding capabilities and a more integrated Intelligence Community. But above all, the publication has changed in response to the preferences and habits of each President.

President Kennedy wanted the Checklist, as it was known then, to be short and to the point. It should be small enough, one aide said, to “fit into a breast pocket so that the President could carry it around with him and read it at his convenience.” Kennedy also insisted that it be written in plain, conversational English, stripped of the jargon and officialese that characterized most intelligence writing at the time. No “gobbledygook,” the White House said.

Over time, the Checklist began to reflect Kennedy’s pet peeves in language and usage. One word that rankled him was “boondocks.” He found it too colloquial, and told the writers of the Checklist that it was not an acceptable word. But Kennedy was not an overly fastidious editor, and his writers clearly relished the freedom they were given, sprinkling their prose with words like “effervescent”…“ticklish”…and “cuckoo.”

Classification markings were another pet peeve. Kennedy’s aides did not want them cluttering up the text. Regardless of the content, each document was to carry a single marking—Top Secret—stamped at the bottom of the page. This was true even if the information was based on diplomatic reporting or unclassified news accounts. So while you will see a lot of what can rightfully be described as over-classification in today’s release, the reason was to streamline the production process, and to make the document easier on the eye. Ahh…the good old days.

In both its content and style, the Checklist also testified to President Kennedy’s breadth of expertise. Since Kennedy was so well versed in intelligence issues, each item in his Checklist was spare and direct, without much background or explanatory information. The authors focused only on what the President did not already know, meaning that a lot of important intelligence was left out of the document. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, for example, photographs and other pieces of intelligence that were passed to the President through separate channels were often omitted from the Checklist. As one editor said: “Why summarize what the President already knew?”

After only a few months of producing the Checklist, the authors had gotten so much feedback from Kennedy that they were able to anticipate his intelligence needs and draft a document to meet them. They understood the kind of writing he liked, the issues that mattered to him, and how he wanted them explained. A bond of trust had formed between them and the President that would last throughout his time in office. One senior officer later said the relationship was going so well that it seemed like “heaven on earth.”

But one of the eternal challenges of the PDB is that what works for one President rarely works for the next one. You almost have to start from scratch each time. That is certainly what happened when President Johnson took office.

During the Kennedy Administration, the Checklist was not disseminated very widely. At first it went only to the President and to the Director of Central Intelligence, and later to the Secretaries of State and Defense. But one of Kennedy’s aides told the Agency that “under no circumstances should the Checklist be given to Johnson.”

So when Johnson took office, Agency editors had no idea how familiar he was with the subjects they had been writing about in the Checklist. It was clear that he needed more background information in the articles than Kennedy did. But how much more? The editors wanted to give the appropriate context, but they worried that it if they went too far, they would appear condescending and might alienate the new President.

Their first effort, delivered the day after President Kennedy’s assassination, included five rather lengthy items and several notes. It did not seem to hit the mark, though it was hard to tell. When the President was briefed on it in the morning, he did not say much in response. He seemed mostly relieved that nothing in the document required his immediate attention, understandable in light of the trauma and mourning that our Nation was experiencing.

As the months went by, it became clear that Johnson was not reading the Checklist. Part of the problem was that, early on at least, he preferred to get his intelligence informally, in meetings and through conversation, instead of from written products. Johnson may have also harbored a built-in bias against the Checklist, since it had been deliberately withheld from him when he was Vice President. But the main problem was the format. The Checklist had been created for President Kennedy, and in many respects it was still his product, designed to match his preferences and work habits rather than Johnson’s.

So the editors of the Checklist decided to change course. They gave the document a new name, the President’s Daily Brief. They repackaged it, adding longer articles that supplied greater detail as well as thoughts on future trends. And they delivered it in the afternoon, not the morning, since Johnson liked to do his reading at the end of the day, often in his pajamas while lying in bed.

After several test runs, the first official PDB was published on December 1, 1964. Senior aide Jack Valenti returned it with a handwritten note the very same day: “The President likes this very much.”

As with Kennedy, Johnson’s PDB did not include material that he had already received through briefings, or that he was getting from other intelligence products. It is worth emphasizing here that the PDB was never intended to be the only source of intelligence for a President, and it never has been. Throughout the PDB’s existence, Presidents have also gotten intelligence from the military and other departments of government; through briefings, meetings, and informal conversations; and from longer forms of analysis like National Intelligence Estimates.

But to say that Presidents get their intelligence from a variety of sources in no way minimizes the importance of the PDB. There is no denying the utility of the product to Kennedy and, after several changes, to Johnson as well. And as the documents we are releasing today make clear, the PDB provided them with critical insights as they charted our Nation’s course amid the challenges of a turbulent decade.

* * * *

Looking down from history’s summit at the challenges and crises of the past, it is human nature to see them as less complicated and dangerous than those we face today. The threats have either subsided or disappeared, the standoffs have long since been resolved, and hindsight has shown us all the answers—most of them, anyway—to the questions that were so vexing back in the day.

So the past does seem a lot simpler than today’s world—until, that is, you jump in at just about any point in the narrative contained in these documents and start reading, putting yourself in the shoes of the man for whom they were written.

I took a couple of hours on a recent evening to do just that. And doing so quickly restores one’s sense of perspective.

These pages remind us, for example, that while President Kennedy was deciding how to stop Moscow from establishing a nuclear arsenal in Cuba, the rest of the world wasn’t standing still for him.

India and China were engaged in a fierce border war.

The Vietnam conflict—especially the presence of North Vietnamese troops in Laos—was a persistent concern.

Civil wars were raging in Yemen and the Congo, countries that tragically have had more than their share of fighting over the years.

Warsaw Pact countries launched unannounced military exercises in Eastern Europe, and the East Germans resumed work on extending the Wall along their border with West Germany.

The fact is, America has faced an unending series of national security challenges ever since we emerged at the end of the Second World War as the preeminent global power. Having assumed the duties and obligations that go along with leading the Free World, our country’s most pressing foreign policy need in the postwar era was not only to counter the relentless Soviet military and clandestine threat, but to obtain timely, accurate, and insightful information on our adversaries’ actions and intentions.

And so it took the United States 171 years before it finally did what every other great power had done: establish a comprehensive intelligence service for both peacetime and war.

I joined that service, the Central Intelligence Agency, in 1980. I believed in its mission then, and I believe in it today.

We have had the great fortune over the past 68 years to play an important role in keeping this Nation strong and its people safe from the constantly evolving array of overseas threats. And though we are exceptionally proud of the work we do, we have not been a perfect organization.

We have made mistakes, more than a few, and we have tried mightily to learn from them and move forward as a smarter, more capable organization.

And ever since the Agency’s founding during the Truman Administration, its single most important mission has been to give each President and his senior advisors the clearest possible picture of the world as it is, rather than as we would like it to be. CIA endeavors to be a trusted, authoritative source of information and understanding in answering any President’s most crucial questions, particularly in times of heightened risk and danger.

The Cuban Missile Crisis is an iconic example of the Agency marshaling its technical, operational, and analytic strengths to help the Commander in Chief resolve a delicate standoff—peacefully and successfully—amid the highest stakes imaginable. In the pages of the President’s Intelligence Checklist, and in far greater detail in briefings and other products and venues, CIA offered precise, up-to-the-minute information tailored to Presidential requirements, highlighting its essential role in supporting every President of the modern era.

But it doesn’t take a nuclear confrontation to demonstrate the utility of the Agency’s Presidential support. Throughout the documents released today, you will find reports that reflect a truly global scope—all the overseas issues that demand some amount of the President’s time and attention—presented with bottom-line assessments, significant detail, and helpful context for breaking events with which the busy reader might not be familiar.

During the Johnson Administration, for instance, the PDB was well received at the White House during the outbreak of civil war in the Dominican Republic in April, 1965. It was a complex situation in a country that wasn’t often in the headlines, and LBJ’s press secretary, Bill Moyers, observed that President Johnson read the PDB “avidly” throughout the crisis.

Objectivity, too, is critical to Presidential support. CIA was chartered as an independent agency unique in government, free of departmental bias and serving as a dependable source of available information—good news and bad. It’s an essential role, albeit a challenging one.

For just as collecting intelligence often requires physical courage, reporting it requires intellectual courage—the proverbial ability to speak truth to power. And that quality shows in the Agency’s coverage of the conflict that overshadowed all others of the era—Vietnam.

It is certainly true that CIA missed some important calls, most notably before the Tet Offensive in January 1968, when CIA Headquarters failed to pass along the warning from CIA’s Station in Saigon that an unprecedented enemy offensive was at hand.

But the fact remains that CIA estimates of the enemy’s order-of-battle and staying power were consistently more ominous—and, as events would prove, more accurate—than those produced elsewhere.

Senior White House staffers occasionally expressed concern over the PDB’s perceived negativism on Vietnam. Bromley Smith, the NSC’s Executive Secretary during the Johnson Administration, told an Agency officer at the time that “you’re going to break the President’s heart. He thinks things are much better today, but that’s no reason for not writing it as you see it.”

* * * *

In covering the world of 2015, we at CIA are still writing it as we see it. Our contributions to the PDB, which today is published under the auspices of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence at CIA Headquarters, benefit from the enormous range of talents, skills, and disciplines that CIA brings to bear in fulfilling our global mission. Drawing on the intelligence and ground truth provided by the Agency’s worldwide network of Stations and Bases, as well as on the expertise and insight of our all-source analysts at Headquarters and overseas, we put together products, in the PDB and elsewhere, that enable the President and his senior advisors to see an issue in its entirety, with the risks, challenges, and opportunities clearly delineated.

And like our predecessors, who adapted to the needs of the day by developing the PICL and the PDB, we too are taking steps to optimize our relevance and our effectiveness in our own time. When the PDB is sent to the Oval Office today, for example, it arrives on a tablet computer—an iPad—instead of paper.

Indeed, the transformational effect of information technology is the single most decisive factor in setting today’s world apart from that of the 1960s. Along with the end of the Cold War, both the cyber realm and social media have made the planet smaller and dramatically more interconnected. And those developments in turn have had a profound impact on the mission of the Central Intelligence Agency.

To begin with, cyber technology has created an entirely new domain for human interaction. And though it presents boundless opportunities for advancing our national interests, it also enables individuals and small groups—not only nation states—to inflict great harm on our national security.

When it comes to intelligence operations, digital fingerprints might enable us to track down a terrorist. But the digital world also makes it harder to maintain cover for our current generation of clandestine officers, who, for example, almost certainly used social media sites before they even began their Agency careers.

Moreover, the erosion of boundaries between domestic and foreign communications has raised complicated legal and ethical questions for our profession. In President Kennedy and Johnson’s day, the enormous signals collection effort against the Soviets and their client states—whose communications networks were largely segregated from those of the Free World—carried little or no legal ambiguity. But the terrorists we face today routinely use the same channels everyone else does, and the public debate rightly continues over how to strike the balance between the need for security and the need for privacy.

When I asked a group of our senior officers last fall to ponder CIA’s future and come back with a strategic plan for modernizing the Agency, they agreed that, among other things, we had to do a much better job of embracing and leveraging the digital revolution. Consequently, under our Modernization Program launched last March, we are adding a fifth Directorate to the Agency as part of the biggest change to CIA’s structure in five decades: the Directorate of Digital Innovation.

When this new Directorate is up and running on October 1st, it will be at the center of the Agency’s effort to inject digital solutions into every aspect of our work. It will be responsible for accelerating the integration of our digital and cyber capabilities across all our mission areas—human intelligence collection, all-source analysis, open source intelligence, and covert action.

And though the documents we are releasing show us that today’s world is hardly unique in its complexity and danger, it nonetheless harbors a wider variety of threats than the world of the 1960s. These contemporary challenges often overlap, change rapidly, and require a multidisciplinary approach. And as the Intelligence Community has learned in the years since the 9/11 attacks, integrating disciplines and capabilities is a powerful way to magnify our effectiveness.

So on October 1st, ten new CIA Mission Centers will cover every issue we face—six focused on regions, like Africa and the Near East; and four focused on functional issues, such as terrorism and weapons proliferation. Each center will pull together all the tremendous talents and skills previously stovepiped into separate groups, promoting collaboration among Agency specialists in operations, collection, analysis, technical capabilities, and support.

These are times of tremendous opportunity for CIA. Our plan will bring the same kind of teamwork to CIA Headquarters that one finds in our Stations and Bases overseas, where it has helped us succeed against our toughest targets. These changes build squarely on our strengths, enabling the Agency to do an even better job of operating in the multidisciplinary and ever-more technical environments that come with our mission today—and that will be even more prevalent in the years ahead.

Before I conclude, I want to thank you all for coming out today to mark this occasion. The documents released today touch on history, the Presidency, the intelligence field, and democracy itself—subjects that were of great interest to me back when I was a graduate student at UT and are of even greater interest to me today.

If any of this kindles your interest in joining the Agency, Chancellor McRaven can tell you some pretty good stories on what it’s like to work with us. And I hope to see you among the new officers that I swear in every couple of weeks or so.

My own path to CIA started here at UT, where I interviewed for an Agency job when my wife thought I was getting far too comfortable being a grad student. And it has been my deep privilege since then not only to serve as a CIA officer, but to serve Presidents—Democrats and Republicans alike—who devote so much of themselves to the extraordinarily hard and consequential work of leading our Republic.

Each of us who has ever had a hand in producing the PDB or PICL feels deeply honored to have played a role, however small, in helping the President make the decisions on which our national security rests. Every book is written, edited, and delivered not only as a review of intelligence, but as an expression of respect.

And none better captures this spirit than the President’s Intelligence Checklist of November 22nd, 1963, the day we lost President Kennedy. Its pages are largely blank, except for the following words:

For this day, the Checklist Staff can find no words more fitting that a verse quoted by the President to a group of newspapermen the day he learned of the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba.

Bullfight critics ranked in rows

Crowd the enormous plaza full;

But only one is there who knows

And he’s the man who fights the bull.

Thank you all very much.

Related Links:

Press Release: CIA Releases Roughly 2,500 Declassified President’s Daily Briefs at Event Hosted by LBJ Presidential Library and University of Texas at Austin

Booklet – President’s Daily Brief: Delivering Intelligence to Kennedy and Johnson

FOIA Document Collection: The President’s Daily Brief

Related Topic :

« The Challenges of Ungoverned Spaces » by John O. Brennan (13-07-2016).

« The Overarching Challenge of Instability » by John O. Brennan (29-06-2016).

« ISIL IS a Formidable, Resilient, and Largely Cohesive Enemy » by John O. Brennan (16-06-2016).

« CIA : Between Transparency and Secrecy » » by David S. Cohen (21-04-2016).

« Instability Has Become a Hallmark of Our Time » by John O. Brennan (03-03-2016).

« Good Intelligence Is the Cornerstone of National Security Policy » by John O. Brennan (16-11-2015).

« CIA & The OSS Legacy » by John O. Brennan (07-11-2015).

« Addressing Challenging and Consequential Issues of Our Time » by John O. Brennan (05-11-2015).

« Intelligence : Between Policy Success and Intelligence Failure » by John O. Brennan (15-10-2015).

« The CIA of the Future » by David S. Cohen (15-09-2015).

« Democracy Does Not Keep Secrets Merely for Secrecy’s Sake » by John O. Brennan (15-09-2015). »U.S Intelligence in a Transforming World« by John O. Brennan (13-03-2015).