With Josephine Baker’s induction into the Pantheon, many will remember the struggle of a woman who made good use of her popularity to fight racism and promote the emancipation of blacks by supporting the American civil rights movement, and then by becoming involved as a Freemason from 1960 onwards, in the fight for equal rights for all. She is today honoured not only for her action in favour of universal fraternity, as exemplified by the brotherhood resulting from the many children she adopted in the four corners of the world, but also for her true fight for the freedom of France.

Joséphine Baker – Studio Harcourt Photo (1948)

Former Special Branch personnel are particularly proud to see one of their peers being paid tribute in this way, but many are unaware of what she actually did. That is why the authors of this article believed it useful to tell the story using memoirs and books that evoke the struggle of the woman in the shadows who took the light so well.

And she did not shy away from any risk for France.

When she was contacted in September 1939 by Captain Jacques Abtey of the German section of the French counter-espionage service headed by Captain Paul Paillole, she immediately agreed to make herself available to the service with these words: « It is thanks to France that I have become what I am. I will be eternally grateful to her. The Parisians have given me everything, especially their hearts, I give them mine. I am ready, Captain, to give them my life today. You may dispose of me as you wish.»

From misery to dance

A dancer at the Folies Bergères, the artist was 33 years old at the time and had become a mythical music hall figure.

The rise of the little girl from Missouri was prodigious. Her mother, of mixed black and Indian origin, and her father, a drummer of Hispanic origin from Saint Louis, had put together a song and dance act, performed in bars and music halls.

Her real name was Freda MacDonald and she was the eldest child in the family, but about a year after she was born her father left. Her mother, who held the little girl responsible, behaved with great brutality. Cold, stench and misery were the soil of her childhood. At the age of eight, she worked as a maid in a white woman’s house, sleeping with the dog by the coal pile. She eventually was taken out of this world after her boss scalded her to punish her, and the neighbours alarmed by the child’s screams. When she was eleven, she witnessed an event that would leave a lasting impression on her, the East Saint Louis ghetto race riot. People were burned in the fire, and she watched as fugitives were hunted down like animals. At the age of thirteen, after a violent break-up with her mother, she marries, for a short time, a sleeping car boy, Willie Wells.

Dancing was already her world. On the streets of St. Louis, she learned the typical moves of jazz dancers in the 1920s in the United States. Raised in the Baptist tradition, she loved religious ceremonies where music and rhythm drove the faithful to stomp their feet, clap their hands and sway in a hypnotic atmosphere. She is imbued with the idea that the soul can express itself through the body.

So, after working as a waitress, she joined a family band of street musicians, where she learned to play the trombone. There, at the age of fifteen, she married Willie Baker, whose name she kept, and realised her dream of joining a touring band’s corps de ballet. At first she was auxiliary, but eventually made a name for herself as a comic girl: she pulled faces and moved with irresistible gusto, capable of any posture without ever stopping to squint.

Scandal and enthusiasm: the Revue negre

At the same time in Paris, in 1925, a real craze erupted among artists for exoticism, particularly African. The painter Fernand Léger, who had just seen the Negro Art exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, suggested the administrator of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées to present a show entirely produced by black people.

The troupe to which Josephine belonged was approached. She was then nineteen years old, danced solo and had begun to make a name for herself. This was her first contact with France.

Josephine expected everything from this country, especially the opportunity to escape from the particularly heavy racial discrimination in her country. Paris will offer her more than a home, it will make her a star.

Paris will offer her more than a home, it will make her a star

But if this body stands as a work of art that exalts the world of the arts, if the name Josephine Baker is also synonymous with freedom and openness to the world, Eros, which is conducive to fantasy, is indignant to some. Catholics took offence, to the point that the Church became alarmed. Nevertheless, the star decided to stay in France.

She became the companion of Giuseppe Abatino, known as Pepito, who passed for a gigolo and turned out to be a remarkable impresario during their ten-year union. It was he who organised a world tour for her. The tour began in Vienna, where right-wing students wanted to prevent coloured artists from performing. The Church, offended by such tumultuous displays of sensuality, got involved. Josephine is horrified. In Argentina too, she says, « the Catholic parties hounded me from station to station, from town to town, from stage to stage. In 1929, the Munich police banned the show ».

The 1930s arrived. She returned to France, the only country for her « where one can live easily ». She was a dancer at the Casino de Paris, which had become a respectable music hall. Josephine was transformed: she dressed simply and started to sing. La petite Tonkinoise and J’ai deux amours are on everyone’s lips. In 1934, she tried her hand at operetta and had a real success in Offenbach’s La Créole.

However, her desire to return to her country to make a name for herself on Broadway ended in failure. Realising that she definitely did not belong there, she returned to Paris to lead a new revue at the Folies Bergères. Pepito died suddenly in the spring of 1936. In 1937, by marrying Jean Lion, a rich sugar broker, she obtained French nationality. The same year she passed her pilot’s licence.

The star and counter-espionage

When war broke out in 1939, the black star was caught up in racism. The overtones of Nazism and the cruelties of the Aryan ideal could already be heard. A theatre agent put her in touch with Captain Jacques Abtey, an energetic and athletic 33-year-old from Alsace, a blond with a high forehead and pale blue eyes.

Even before the war, the head of the secret service section working against Germany had had the idea of using French actors when travelling abroad.

« When the young Captain Abtey spoke to me for the first time about Josephine Baker, » Colonel Paillole said, « I was reluctant. We were wary in the 2nd Bureau of Mata Hari-like enthusiasm. I was afraid that she was one of those brilliant personalities of the entertainment world who, when put to the test of a real danger, quite different from their usual afflictions, break like glass; he told me that Josephine was steel.» Under Jacques Abtey, Josephine Baker became an honourable correspondent.

She « knew nothing of the intelligence service and soon became an H.C. of the first order,» says Abtey. « This universally known woman could not be a spook. Nor could anyone suspect her of covert operations. It was her figure as Josephine Baker that drew attention, masking her secret activity. (…) Better still, I myself managed on certain occasions to go completely unnoticed by travelling with her on a false passport as a secretary or artist.»

« Mission accomplished!

A long road of adventures began for Josephine and her ‘case officer’. The star’s world of intelligence quickly encompassed that of ministers, embassies and even kings.

In 1940, Jacques Abtey was asked to set up a liaison with the Intelligence Service for the French Special Services, in order to ensure a permanent exchange of information and to receive instructions for joint action. It was decided that he would accompany the star on his tour of Portugal and South America; he would blend in with the troupe with a passport in the name of Jacques-François Hébert. Joséphine began her job as a cover, which involved enormous risks, especially since she had had her partner’s passport marked « assistant to Madame Josephine Baker ».

For this first trip, they set off with a summary of the information gathered so far by Paul Paillole’s department, reproduced in cipher and sympathetic ink (location of the main German divisions, personnel, equipment, airfields and even a photo of a barge that the Germans were planning to use for an invasion of England).

As everyone rushed to see the star, Abtey went unnoticed, he was part of the baggage so to speak. At the Lisbon embassy, through the British air attaché, he came into contact with a member of the Intelligence Service. Josephine, who returned to Paris alone, could tell Paillole: « Mission accomplished!»

As she needed to replenish her finances, damaged by the expedition to Lisbon, which she was keen on taking on, she took over La Créole in Marseilles. From then on, she would never accept any financial help for anything she did for the Resistance or the soldiers of the Alliance.

Abtey remained in Lisbon to work out the arrangements for collaboration with the British. The French service would be based in Casablanca and mail would be routed through Portugal. When he returned to Marseilles for the premiere of a show by Josephine, he told her that he needed her for the rest of his missions and that they were going to settle in Morocco. Not hesitating for a moment, she interrupts the performances on the ground of flailing heath and had her luggage transferred to her Dordogne castle. But as fond as she was of her animals, her Great Dane, female chimp, lion monkey, marmoset, and two white were seen arriving in her cabin on the boat headed for North Africa.

They also embark with the latest intelligence summary. Upon arrival at Casablanca however, Abtey has such difficulty obtaining a visa for Lisbon that Joséphine decides to go in his place. « In a suitcase,» he said, « she carried Paillole’s synthesis that I had transcribed for her in sympathetic ink on a musical score. She was amused to see me writing with water. It was the first mission she was going to carry out alone abroad. To justify her presence in Lisbon, she gave a few performances there and returned radiant.»

Mosaics, orange trees and marble columns

She then retreated to Marrakech where two personalities opened their arms to her: a first cousin of the Sultan, H.H. Moulay Larbi el-Alaouï, and the pasha of Marrakech, H.E. Si Thami el-Glaoui. Seduced by this city, she settled with her retinue, including Abtey, in a dream residence at the end of a cul-de-sac in the Medina: a mosaic-covered vestibule, an interior garden with marble columns, orange trees and a babbling fountain. She is struck by the spirituality that emanates from this enchantment. But the work continues.

Despite the dangers of going to Spain, then under the occult control of the Germans, she decided to perform there, as this trip was favourable to their mission. She returned with the notes she had taken on embassies established in Spain and political circles, attached to her underwear by a safety pin.

But suddenly her health stopped her momentum: she had peritonitis and her case was very serious. A camp bed was set up next to her for Abtey to watch over her. But because he often had to meet people for the needs of his mission, she still helped him in her own way as under the pretext of assisting « his » patient, he could hold most of his clandestine meetings in her room.

However, from relapse to relapse, and for nineteen months Josephine led an unceasing struggle for life.

One day, a tall, open-faced man, the American vice-consul Bartlett, arrived at her bedside: « Miss Baker being of American origin,» he said, « no one will find it surprising that I should pay her visits.» Abtey had indeed made new contacts with the Americans, who had entered the war. It was the same Bartlett who would one day tell them that serious events were afoot.

In mid-October 1942, Abtey was offered to head the 2nd Bureau of the military staff of a France Combattante movement that had just been formed in Casablanca. And Paillole’s agents were approached to neutralise, under the direction of General Béthouart, the higher command of the troops in Morocco which were under the direction of the Vichy government.

On 8 November 1942, the flak was unleashed against the first allied planes. It was the beginning of the landing in North Africa. Josephine exults, Abtey saw her « leaping from her metal bed, launching herself onto the terrace, her skinny body clad in pyjama trousers and a nasty knitwear, her feet bare » and, raising a fist to the sky: « I always told you! That’s what the Americans are ! » She followed the battle from the clinic’s roof.

On the second day of the fighting, and despite her weakness, she insisted on accompanying the representatives of France Combattante that were going to make themselves available to the American staff: a stretcher would allow them to move under the protection of a Red Cross ambulance.

Thousands of soldiers listen to her sing

Finally, on 1 December, Joséphine left the clinic. In Marrakech, Si Mohamed Menebhi puts a pavilion in his palace at Finally, on 1 December, Josephine left the clinic. In Marrakech, Si Mohamed Menebhi puts a pavilion in his palace at her disposal. But paratyphoid struck her again and she was furious at not being able to join her treating officer. However, on 1 February, barely recovered and with the scars from her long stay in the clinic not fully healed, she took to the stage at a black American soldiers’ home (the whites had their own club) to help people of her colour. General Clark, who attended the show, came to congratulate her at a reception attended by the highest ranking officers of the Allied Forces. She was reborn as a star and made herself available to the high command of the troops involved, to give free shows to support the morale of the soldiers. And when she was penniless and had to give a series of performances at the Rialto in Casablanca to bail herself out, the first was a gala for the French Red Cross. It was a huge success. J’ai deux amours, mon pays et Paris (I have two loves, my country and Paris) unleashed a sometimes heartbreaking emotions.

And while Abtey, who had left the Corps franc headed by Giraud, waited for the opportunity to fly out to join de Gaulle, she toured the camps (nearly 300,000 men were in tents or shacks). She hit the stage several times a day; her dressing room is a tent. Near Oran, the stage was set up in the middle of a field, with several thousand soldiers surrounding it. In Mostaganem, she was asked to sing in the public square because the soldiers were facing hostility from the population, which was mainly Italian and Spanish, and the chief of staff had decided to mix them with the crowd, hoping to arouse the rallying power of the artist.

While singing, she descended among the spectators, taking babies in her arms and handing them to the soldiers. This is how she managed to create the atmosphere of brotherhood that she longed for.

Thousands of kilometres across the desert

When she returned, exhausted, Paillole and many members of the 2nd Bureau had arrived in Algiers, as well as General Catroux, representing de Gaulle. Abtey went to work for the BCRA, while Josephine accepted a tour of the British camps in Libya and Egypt. One might think that her activity in the Resistance would end there, especially as there was no question of her returning to France where, since 1941, the Nazis had forbidden the entry of any person of colour into the occupied zone.

Yet the duo carried on with their fight, but their action took a different turn. Instead of focusing on German activities the job at stake consisted of observing the Muslim world where ancestral rivalries were resurfacing. Josephine had a great knowledge of the Arab world and, she put the interests of France above all else, she sincerely loves her Muslim friends. It is in this spirit that she worked.

Accompanied by Abtey, she leaves for the Middle East. Under the guise of a propaganda tour, under the high patronage of De Gaulle and for the benefit of the Resistance in metropolitan France, she held shows for the FFL troops.

Always benevolently and in order to finance the operation, Josephine threw a big party at the municipal theatre in Algiers. De Gaulle was among the spectators, he congratulated her and gave her a small gold cross of Lorraine. Worthy of notice, Josephine had a ten-metre long French flag decorated with a huge cross of Lorraine that she unfurled on the stage, something that she did throughout her tour.

She suggested taking with them one of her friends, Madani Glaoui, nephew of the pasha of Marrakech. A young man full of grace and energy and supporter of de Gaulle, his name was likely to open up doors for them. And here they are, off on an extraordinary journey, the three of them in a jeep, their luggage following in another vehicle, Josephine in military field dress. She will travel thousands of kilometres across the desert.

In Sfax, a destroyed city, she offers the proceeds to the victims. In Alexandria, the trio is invited by Prince Mohamed Ali, who is interested in their mission. In Cairo, a great Franco-Egyptian function and banquet presided by King Farouk is given in the star’s honour. In Beirut, she was host to the outgoing President of the Republic, the ambassador and the crowned heads of Greece. To raise money for the Resistance, Josephine auctioned the gold Cross of Lorraine given to her by de Gaulle, raising 350,000 francs.[1]

Damascus, Jerusalem, Tel-Aviv, Jaffa, Haiffa, then Cairo again; on every stage, Josephine flew her big flag, symbol of the resurrection of France. The outcome of the mission: a propaganda action and more than three million francs for the Resistance.

However, in Beirut, at the election of the new president of the Lebanese Republic, the French candidate was defeated and the Arab Union scored the first point. The information gathered by Abtey was all transmitted to Algiers and, with the revolt rumbling in Lebanon and the demonstrations in Cairo, he decided to return as soon as possible to the Algerian capital to report in person the suggestions made by the Lebanese personalities he had met.

France’s defeat in the Middle East is on everyone’s mind and is already changing opinions. For the duo things there clearly were turning sour. The nationalist movements were of high interest to French, American and British intelligence services.

But Josephine’s infernal treks through the desert came to a cost and she had to undergo emergency surgery for an intestinal obstruction. The Menebhi Palace, where she was convalescing, was a privileged place to observe the evolution of the Moroccan notables’ attitude towards France.

On the eve of the D-Day landings in France on the Normandy coast, she accepted a propaganda tour to the benefit of Free France in Corsica, which had just been liberated; the aim was a display of ability aimed at the Americans, whose attitude towards De Gaulle had been more than equivocal to the extent that one day, a member of the diplomatic corps advised the star never to board the General’s plane.

Her plane crashed at sea

Shortly after overflying Sardinia on their way to Corsica as a stepstone to set foot in France for the first time in four years, one of the plane’s engine broke down. The sky is criss-crossed by French planes, while theirs loses altitude and eventually descends towards the sea. The pilot shouted « brace yoursleves » and the large rolled-up flag serves as a protective cushion for Josephine. The plane crashed in a spray of water and with its wooden frame shattered, its occupants climbed onto the wing amidst the floating luggage. They had crashed in a cove where a group of black riflemen run to the beach. The gala evening is saved, Josephine will sing for the men who are going to liberate occupied France.

Lieutenant Josephine Baker enlisted on 23 May 1944 and landed in the southern zone with the Women’s Air Force complete with full field dress, besetting gear and helmet for a life as a soldier.

Abtey eventually met her in Paris, at Les Halles, cap on her head, wearing large grey-blue RAF coat sporting French Air Force buttons and large woollen scarf wrapped around her neck; without the required food ration stamps thanks to her connections she had just bought wholesale supplies for the old suburbs folks. She was fully committed to her fight against poverty.

For a series of shows for the benefit of the disaster victims, she was recommended Jo Bouillon’s orchestra. Together they followed the progress of the 1st Army, travelling through the French zone in occupied Germany. In Berlin, she represented France in a grandiose show featuring the great allied nations. In liberated Buchenwald, she went to the bedside of non-transportable typhoid victims.

A new slice of life awaited the star, but with the return of peace and Jo Bouillon now her husband, she will never give up fighting with the astonishing generosity she always displayed, especially for her primary cause: the abolition of racial barriers. To prove that people can live together without discrimination, she adopted twelve children of different origins.

Josephine Baker’s activity as part of the special services got downplayed by some individuals claiming that she was not a true intelligence agent. Without her, however, recognised intelligence agent Jacques Abtey would have never ben able to carry out his missions. Throughout the Occupation, she took considerable risks to « cover » him and sometimes worked beyond her strength for the Resistance. Her decorations bear witness to this. In 1946, she was made the recipient of the Resistance medal in her bed at the Neuilly clinic (due to new health problems) and, in 1961, in her château in Les Milandes, in the Dordogne region, of the insignia of the Legion of Honour and the Croix de Guerre with palm.

Her state funeral in 1975 was unprecedented for an artist.

Alain Juillet and Marie Gatard

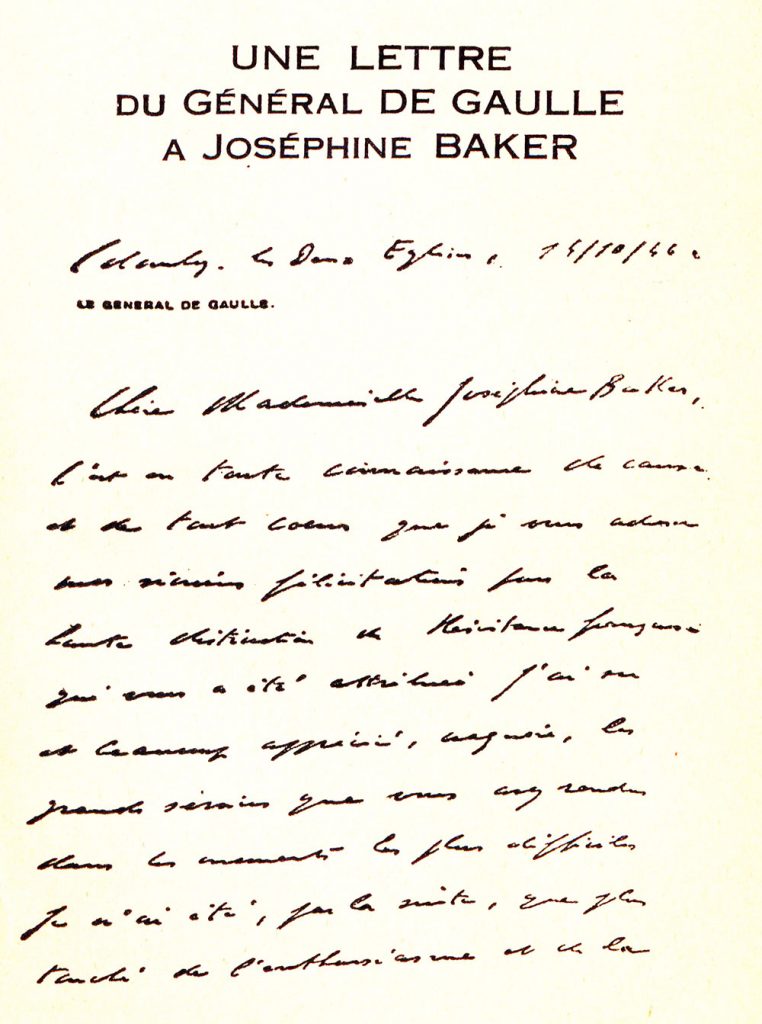

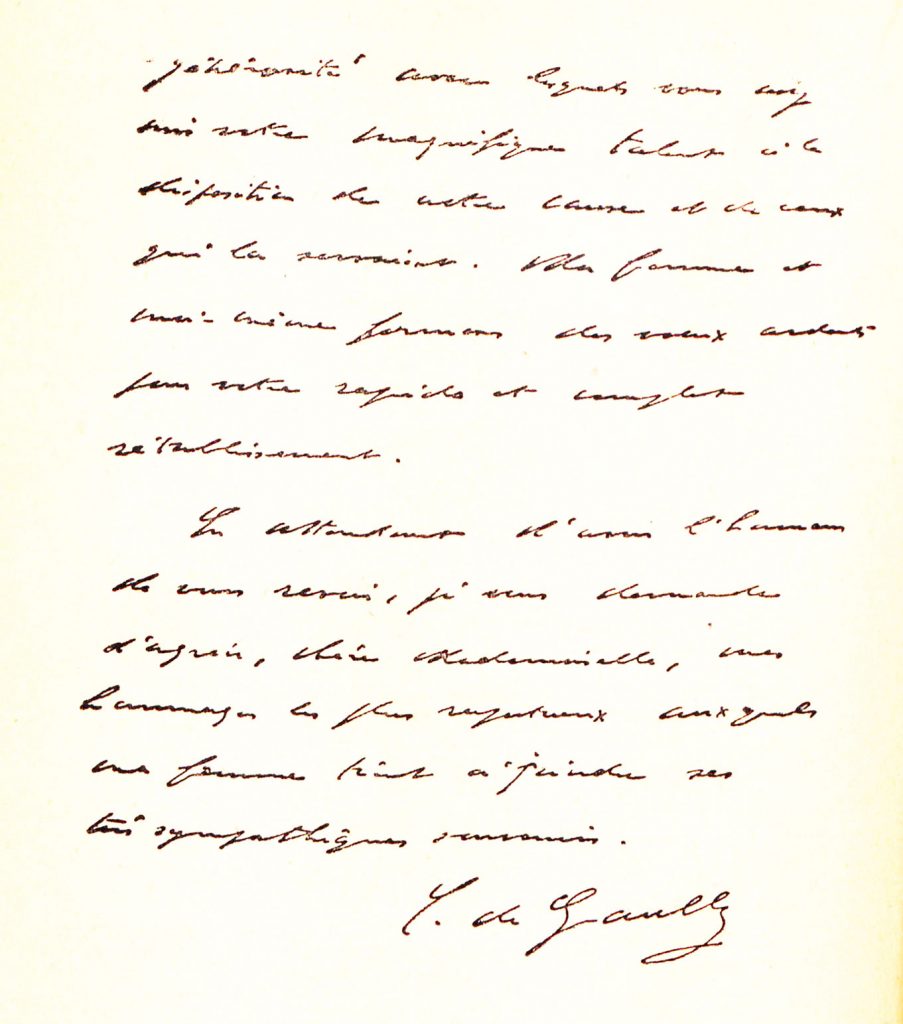

[1] Handwritten letter from General de Gaulle to Josephine Baker published in the book dedicated to her by Major Jacques Abtey: Josephine Baker’s Secret War published by Siboney Editions (1948) and La Lauze Editions (2013) 2nd edition.

Colombey-les Deux Églises, 14.10.1946

Chère Mademoiselle Joséphine Baker

In full awareness of the prevailing circumstances I wish to address you my wholehearted congratulations on your receipt of the High Distinction of the Resistance Française award.

I was in recent years able to see and fully appreciate the great services you rendered at some most critical moments. I was subsequently all the more moved to learn the enthusiasm and generosity you deployed to put your immense talent at the disposal of our cause and those who served it. My wife and I wish you a speedy and complete recovery.

In the hope of having the honour to soon see you again, please accept, Dear Madam, the expression of my most distinguished consideration, to which my wife wishes to add her very fondest memories.

C. de Gaulle

This article was published on September 19, 2021 in issue 256 of the bimonthly Bulletin of the AASSDN, the Amicale des Anciens des Services Spéciaux de la Défense Nationale. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the authors and the AASSDN.

French version : Josephine Baker au Panthéon – Source : AASSDN

Translated by Eric Herbert Bias