Secretary Kendall, Airlift participants recognize 75th anniversary of greatest humanitarian airlift in history By Edward Goldstein, Secretary of the Air Force Public Affairs — Published June 26, 2023 —

Table of Contents

Arlington, Virginia (AFNS) — Seventy-five years ago, midway through a century marred by bloody conflict, the world faced a grave new crisis.

Alarmed by the efforts of their former allies — the United States, Great Britain and France — to support the development of a free economy in a democratic West Germany, on June 24, 1948, the Soviet Union blockaded all road, rail and canal traffic of essential food, medicine and coal supplies to the free people of West Berlin and cut off electricity.

“The situation was extremely dangerous,” wrote historian David McCullough. “Clearly Stalin was attempting to force the Western Allies to withdraw from the city. Except by air, the Allied sectors were entirely cut off. Nothing could come in our out. Two and a half million people faced starvation. As it was, stocks of food would last no more than a month. Coal supplies would be gone in six weeks.”

President Harry Truman had limited options. With Allied forces vastly outnumbered by Soviet combat forces near Berlin, confronting the blockade with an armed convey didn’t look promising. Yet the thought of capitulation — giving up Berlin and allowing the Soviets to dominated western Europe — was a non-starter. “We stay in Berlin, period,” Truman told his key advisors.

That left one audacious option. By agreement with the Soviets, the Allies maintained three 20-mile-wide air corridors into Berlin. This provided the opportunity to mount an aerial supply effort. Yet the odds were high. “It hardly seemed realistic to expect a major city to be supplied entirely by air for any but a very limited time,” McCullough wrote. Indeed, many of Truman’s aides considered an airlift a stopgap measure to buy time for diplomacy. The Air Force’s first Chief of Staff, Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg, however, insisted the Air Force “go in wholeheartedly.” He added, “If we do, Berlin can be supplied.”

Two days after the blockade began, on June 26, 1948, the U.S. chose the airlift option. What followed was the infant U.S. Air Force’s first great triumph, the greatest humanitarian airlift in history. It not only kept the citizens of West Berlin from starving, it gave them hope.

“The Berlin Airlift established a tremendous legacy for the U.S. Air Force »…

Our Air Force demonstrated sustained global air mobility in an operation that may have prevented World War III,” remarked Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall. “The airlift demonstrated how the United States stands by our Allies and partners and serves as an example of America’s values at our best — our country’s commitment to humanitarian relief and our enduring opposition to authoritarianism.”

When the operation began, the airlift’s first commander, Brig. Gen. Joseph Smith, gave it a unique code name. “Hell’s fire — we’re hauling grub,” Smith told aides. “Call it ‘Operation Vittles.’” The airlift — the largest non-combat military operation of the 20th century — was largely run by the U.S. Air Force through the Military Air Transport Service, the forerunner of the Air Mobility Command, with a big assist from the Army, Navy and Marine Corps. British Allies mounted the complimentary “Operation Plane Fare” with help from Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South African air crews and with support from France.

By the airlift’s end on Sept. 30, 1949, in round-the-clock flights in difficult flying conditions, the U.S. Air Force had delivered 1.8 million tons of supplies and the Royal Air Force over half a million tons. U.S. and British pilots flew 92 million miles on 278,228 flights mostly from four primary air bases in the western sector of Germany (Rhein-Main, Wiesbaden, Celle and Fassberg) into three airfields in Berlin: Tempelhof, where pilots had to skirt over apartment buildings on final approach, Gatow, and Tegel, which was built from scratch, with brick rubble from bombed-out buildings used to build runways.

The beasts of burden for the American airlift effort were the two-engine C-47 Skytrain and four-engine C-54 Skymaster transport aircraft. U.S. aircrews worked non-stop, and due to hazardous flight operations, including dense fog that blanketed the Berlin area for most of the winter of 1948-1949, 31 American Airmen perished. American Airmen also faced harassment by the Russians, including 103 cases where searchlights were used to blind pilots, 173 incidents in which Russian airplanes either buzzed transports or flew too close, and 123 cases in which transports were subjected to flak, air-to-air fire, or ground artillery fire — but the Airmen persisted.

When the airlift concluded, Vandenberg said it enabled the fledgling Air Force to demonstrate the ability to make airpower “a true force for peace.” In an editorial, the New York Times wrote, “We were proud of our Air Force during the war. We’re prouder of it today.”

On this 75th anniversary, the number of Berlin airlift veterans has dwindled to a few

Those who can still bear witness about the Air Force’s herculean efforts to save the people of Berlin are still young in spirit. They are honored to share vivid memories of the time when the fate of an entire city, and the course of the Cold War, hung in the balance. Their stories, and those of whose lives were touched by the airlift in other ways, are reminders of a time when ordinary men and women, proud to be among the first to wear the Air Force uniform, did extraordinary things.

The general’s son: Dr. William Tunner, Jr.

Dr. William Tunner, Jr. was a teenager living stateside in late July 1948 when Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenburg appointed his father, Brig. General William Tunner, the architect of the World War II “Over the Hump” supply effort for our Chinese allies, to lead the Berlin Airlift. Dr. Tunner didn’t get to see his father in Wiesbaden until the summer of 1949, when he took advantage of the Air Force offer to dependents of one free round trip a year. “My father took some well-deserved time off in June of that year,” recalls Dr. Tunner. “For him, it had been almost a full year of work, seven days a week with long hours every day. His quarters were a small walk-up, cold-water flat on a side street in downtown Wiesbaden, arranged by Gen. [Curtis] LeMay, at that time [U.S. Air Forces in Europe Commander in Chief].” Dr. Tunner adds, “Aside from any ‘mission’, General Tunner’s concern was always for his men, ‘the team’ — large or small: their housing, families and facilities. You take care of the men; they will take care of the mission.”

Dr. William Tunner, Jr. was a teenager living stateside in late July 1948 when Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenburg appointed his father, Brig. General William Tunner, the architect of the World War II “Over the Hump” supply effort for our Chinese allies, to lead the Berlin Airlift. Dr. Tunner didn’t get to see his father in Wiesbaden until the summer of 1949, when he took advantage of the Air Force offer to dependents of one free round trip a year. “My father took some well-deserved time off in June of that year,” recalls Dr. Tunner. “For him, it had been almost a full year of work, seven days a week with long hours every day. His quarters were a small walk-up, cold-water flat on a side street in downtown Wiesbaden, arranged by Gen. [Curtis] LeMay, at that time [U.S. Air Forces in Europe Commander in Chief].” Dr. Tunner adds, “Aside from any ‘mission’, General Tunner’s concern was always for his men, ‘the team’ — large or small: their housing, families and facilities. You take care of the men; they will take care of the mission.”

Dr. Tunner also noted how his father was determined to get firsthand knowledge of how the operation was going from his aircrews: “He put on his flight suit without any insignia on it and hitched a ride to Berlin. While he was in flight, he would ask ‘What’s going on? ‘What problems do you have?’ And he would see that they were taken care of. He was a workaholic.”

Indeed, Gen. Tunner brought technical innovation and precision to the operation, demonstrating the importance of air mobility, logistics and global reach. Tunner transformed the airlift from a haphazard and dangerous operation into one in which cargo laden aircraft landed in Berlin every three minutes 24 hours a day, in all weather, with unloading times cut from 17 minutes to five, turnaround times cut from 60 minutes to 30 and refueling times at bases in West Germany slashed from 33 minutes to eight. Gen. Tunner insisted that his aircrews always used instrument flight rules to reduce the possibility of mid-air collisions in patchy weather, organized each western Ally-controlled air corridor into an efficient one-way path, and drastically reduced times crews spent on the ground in Berlin. He famously had Red Cross trucks filled with coffee and donuts pull up right next to arriving aircraft, so pilots would not waste time lounging in airfield buildings. In his memoir, « Over the Hump,” Gen. Tunner described his philosophy of operations: “The actual operation of a successful airlift is about as glamorous as drops of water on stone. There’s no frenzy, no flap, just the inexorable process of getting the job done.”

The bottom line to Dr. Tunner was that his father was proud of the group of people that he had working with him. He felt it was they don’t work for him, they worked with him. He was one of them.

The Candy Bomber’s daughter: Denise Williams

Of all the airmen associated with the Berlin airlift, perhaps the best known and most beloved is Col. Gail Halvorsen. Halvorsen, then a 28-year-old First Lieutenant flying C-54 transport aircraft into Berlin, had a chance meeting with Berlin children outside the gates of Tempelhof Airfield. His hour-long conversation with the children led to his initiating Operation “Little Vittles,” the dropping of candy and gum with handkerchief parachutes. The operation spurred smiles and hope throughout the beleaguered city.

While on a rare day off in July 1948, Halvorsen was filming planes landing at Tempelhof and went over to talk to the children he saw outside the airfield’s gates. « I met about thirty children at the barbed wire fence that protected Tempelhof’s huge area,” recalled Halvorsen. “They were excited and told me that ‘when the weather gets so bad that you can’t land, don’t worry about us. We can get by on a little food, but if we lose our freedom, we may never get it back.” Halvorsen reached into his pocket and took out two sticks of gum to give to the children. The kids broke them into little pieces and shared them; the ones who did not get any sniffed the wrappers.” Halvorsen, whose Mormon upbringing on the family farm in Garland, Utah, instilled in him a sense of service to others, was especially touched by the children’s selfless and uncomplaining attitude about the little gum he had to share. He told them the following day he would have enough gum for all of them, and he would drop it out of his plane. One child then asked, « How will we know it is your plane? » “When I come over the beacon, I’ll wiggle my wings,” Halvorsen responded. “Watch that plane and get ready.” On his next flight, Halvorsen pushed three tiny packs of candy and gum attached to handkerchief “parachutes” out the flare chute behind the pilot’s seat on his C-54 and established his legend as “Uncle Wiggly Wings.”

Soon, Halvorsen had the support of his fellow pilots, and then his entire squadron and base, upping the tempo of an operation that eventually dropped 23 tons of candy to welcoming arms. When word of “Little Vittles,” got to the airlift’s commander, Gen. William Tunner gave his full support. “I happily approved all such programs,” Tunner wrote in his memoir “Over the Hump.” “The people of Berlin were fighting for freedom in their own way, with subsistence on minimum diets in constant cold, and I was much in favor of these little extras on their behalf.” When the candy drops were publicized back in the United States by journalists covering the airlift, they became a national sensation. Halvorsen’s unit, the Seventeenth Air Transport Squadron, was daily flooded with candy and handkerchiefs for parachutes by supportive American citizens and candy manufacturers.

The legacy of the ‘Candy Bomber’ lives on in the hearts and minds of thousands of people affected by Halvorsen’s generous spirt and is well appreciated by his daughter Denise Williams. In 1970, Williams, then a high school senior, moved to Berlin when her father assumed Commander duties at Templehof Airfield. There she met “many people who knew about my dad and the airlift and told me many stories.” Her father, she said, “just told us about meeting the children at the fence. He never liked to make it seem like anything big. I didn’t learn until much later about how it had really changed the course of history. He never said anything like that ever. He always talked about Gen. Tunner. He talked about the maintenance people. He talked about the Berliners. He always talked about the children who were at the fence and how they taught him about freedom.”

Williams observed that her father’s simple act of spending time with those children was distinctive. “Even the fact that he would stop and talk to the children at the fence was mind blowing to the Berliners at the time,” she said. “One of the Berlin kids, Dagmar Snodgrass, wrote a book (“Uncle Wiggly Wings: My Love and Admiration for Berlin’s Candy Bomber”) and we’re in close communications. She said at the time, children were not really noticed. The parents were just struggling for survival and the children would listen in on these intense and serious conversations that the parents had, but they were just not really a part of them…She said that what is remarkable about this story that most people don’t pick up is that somebody noticed children and listened to them. Engaged with them. Wanted to talk with them. And wanted to help them. To do something to make them happy.”

Halvorsen and his wife Alta later spent two years in the country he faced off against during the Berlin Airlift, when they lived in St. Petersburg, Russia, from 1995-1997 while on a mission for the Mormon Church. Williams said he maintained the same open attitude toward the Russian people that he had developed over time toward the German people during the airlift. “He was a little worried because of his position before, and he did talk about how when he got on his first airplane there, a lot of Russian officers got on in uniform, and he had little prickles on his neck about it….I think he generally had a feeling of forgiveness for them,similar to the Germans. When he was just starting on the airlift, he had this idea in mind that the Germans were this certain kind of people. And immediately when they started working together that just melted away. He knew they were working for a common cause. A similar thing happened when they went to Russia. He had all these preconceived ideas, and he said, ‘We met all the individuals one by one, and they were just as good as can be.’

Col. Halvorsen, who well into his 90s enjoyed reenacting “Little Vittles” by dropping candy from a plane for Utah schoolkids, passed away in February, 2022, at age 101. One citizen wrote after his death, “Stiffening the resolve and cementing the friendship of the people of West Berlin with a couple of dozen handkerchief parachutes and a pocketful of PX candy bars was the greatest diplomatic investment in history. All honor to you on your last and highest flight, Colonel.”

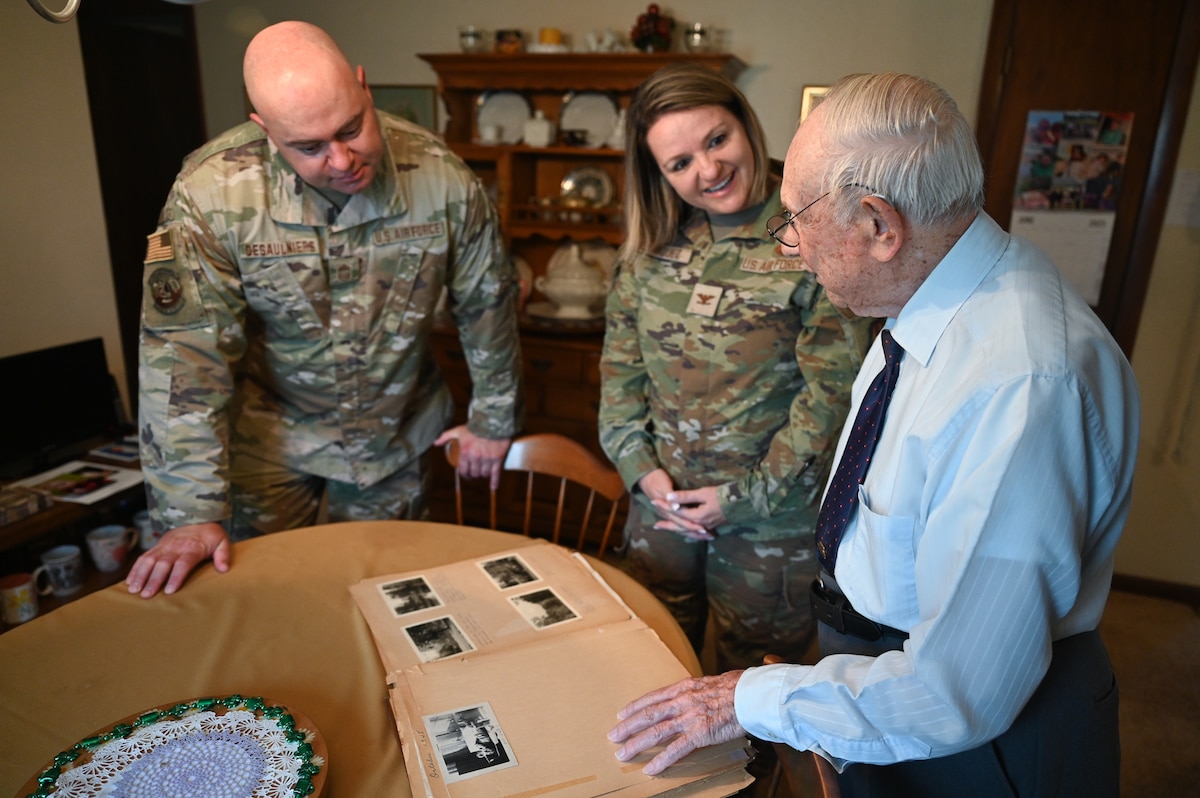

The mechanic/flight engineer: Sergeant Ralph Dionne

Ralph Dionne, the Berlin Airlift Veterans Association’s current president, joined the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1946, shortly after graduating from high school in Nashua, N.H. He hoped to be a pilot, but at 5’ 3” was deemed an inch too short. He trained as an aircraft mechanic instead and was sent to Rhein-Main Air Base near Frankfurt for the airlift. After three months in this role, he was asked to serve as a flight engineer on C-54 transport aircraft flying into Berlin. He participated in 74 supply missions for a total of 300 flight hours during the airlift. After leaving the service, Dionne achieved his goal of earning a pilot’s certificate and flew for 20 years.

The mechanic/flight engineer: Sergeant Ralph Dionne

“When we started working there, there was very little support for the mechanics,” Dionne recalls. “We had to use ladders and flashlights at night. I spent a lot of time on night duty. We were working 12 hours on and 12 hours off for quite a while.” He welcomed the opportunity to be a flight engineer. “It was a serious job, and we knew we were accomplishing big things,” he said.

Dionne observed he rarely flew with the same pilot and crew but never worried “because you have such trust in every one of the pilots. They were great.” He said his ‘hairiest experience’ was landing in a heavy fog. “It’s traumatic when you see the headlights of the car [on the Autobahn along the perimeter of the airport] under the wing and you say, ‘That doesn’t belong here,’” he said. By the time Dionne shouted, “Holy cow, go around, go around!” to his pilot, he was told “Negative, we’re on the ground and rolling.” When assessing the airlift’s impact on the young Air Force, Dionne, said, “It’s great what the Air Force accomplished with the British. My God! This stopped communism in Europe. Stopped it in its tracks. I will always be proud of it, and I am today.”

The flight attendant: Maj. Raymond “Ray” Roberts

Inspired by seeing airplanes flying overhead as a child during World War II, Ray Roberts joined the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves when he was 14 years old. A year later, with his parent’s permission, he started training to be a pilot in the Army Air Corps. At age 16, Roberts flew as a flight attendant on C-54 transport aircraft. “We were making up to three trips a day into Berlin out of Fassberg, carrying nothing but coal, bags of coal,” he said.

On one of his missions Roberts experienced the Cold War up close and personal. “All of a sudden, this Russian fighter pilot came up right up to the side of us, the left side,” he said. “And we had no guns, and we were in the corridor as he sat there right on the wing for about five to seven minutes. He looked us over very closely and vice-versa. Finally, I waved at him a couple times and he waved back and went away. Yes, I did (give him the middle finger), not being smart enough.”

Roberts, a past Berlin Airlift Veterans Association president, said, “Flying in and out of Berlin was to me an outstanding thing. To go in and return and go back, you get to learn after a while how important it really was. You had to have that coal for pure survival along with the other things which were shipped in from Frankfurt. They [the Germans] treated us wonderful and they still do.” Roberts remained in the Air Force for 20 years and as a pilot flew the F-102 interceptor aircraft and T37 jet trainer. “I loved it,” he said.

The weather observer: Chief Master Sgt. Emedie “John” Mazzella

John Mazzella, son of Italian immigrants, was drafted in late 1946. After two days of service, he was discharged due to the official end of World War II (December 31, 1946),but he then enlisted for 18 months. He volunteered for an Army Air Corps weather observer program and found his calling. “I came out of West Virginia with a high school education,” he said. “I was a C student. But when I became a weather observer, the weather forecasters around me—some were master sergeants, some were lieutenants and captains—they oozed with intelligence. And man did I ever eat it, drink it, slept it. They made me the man I am today.”

“We had about 35 people in the Weather Center, and it was our job to plot weather maps,” Mazzella observed. “There were times when it was such a precarious weather situation that our forecasters insisted we plot the weather maps every hour, every three hours, for 24 hours a day. The weather patterns in some cases ended up over Iceland and then came crashing down on England, over France and Germany. We relied a lot on pilot reports.”

Today, Mazzella, still an active ballroom dancer at age 97, keeps a pocket card in his wallet with facts and figures about the Berlin Airlift to tell folks how important it was that we “kept our mission to keep two million Germans from starving.”

The German boy turned U.S. Air Force pilot: Col. Wolfgang Samuel

By age 13, Wolfgang Samuel had already experienced living in Berlin under heavy bombing by the U.S. 8th Air Force and British Royal Air Force during World War II and escaping to the west from the Russian zone of occupation following the war. By 1948, he was living in a displaced persons camp with no sanitation or water next to Fassberg Air Base with his mother Hedy and sister Ingrid. His incredible journey to becoming a decorated U.S. Air Force pilot was about to begin.

“In those days, I didn’t have any heroes,” Samuel said. “But when a C-54 crashed near our camp, a couple days later I went out there. It was a sad experience. I didn’t understand these Americans. Three years earlier in 1945 they bombed me when I was in Berlin, and now they were dying to save the city of Berlin. I very much understood what was being done in terms of delivering food and coal to the people of Berlin. And so, these Berlin airlift flyers really became my heroes. I wanted to be like them. Of course, I was a refugee. I knew that would never happen. Well, you can never anticipate what fate has in store for you. I ended up in the United States at age 16 [after his mother married an American Airman and immigrated]. I couldn’t speak a word of English and had maybe an eighth-grade education. Eleven years later I was conducting spying flights against the Soviet Union. Only in America!”

Indeed, Samuel enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, and over a 30-year career, helped support U-2 reconnaissance flights during the Cuban Missile crisis, conducted intelligence gathering missions against the Soviets over the Barents and Baltic seas and received three Distinguished Flying Crosses for his gallantry in an EB-66 electronic warfare aircraft escorting strike forces over North Vietnam. “I was obviously an immigrant,” Samuel said. “I wanted to do more than just make money. I wanted to serve my country which had been very good to me. So those 30 years of service, including four years of enlisted service, I gladly gave.”

In reflecting on the airlift’s legacy, Samuel states, “I think it’s a very understated event, when in fact it was probably the most important confrontation between East and West. As a result of the Berlin Airlift, these flyers didn’t just save the city of Berlin; their actions resulted in the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and put a stop to further Soviet expansion. Too few Americans know about this, but that’s the legacy of those flyers.”

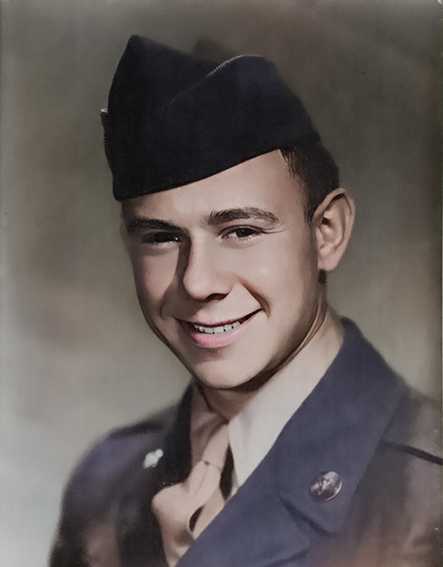

The telephone/teletype operator: Staff Sgt. Bruce Albertson

In his high school junior year in Brewton, Alabama, Bruce Albertson interviewed local businessmen and determined job opportunities in the community were not good. He made a decision. “I bugged my mother day and night until she signed the consent form for me to go into the military at age 17,” he said. Albertson joined the Air Force and was stationed with the Airways and Air Communications Squadron, working in communications handling teletype, facsimile and telephone operations at Fassberg and Rein-Main air bases. His days were long. “As the old saying goes, the day is done when the job is done,” he said. “I enjoyed my time in the military. I never had a bad assignment.” Albertson added, “It was the greatest humanitarian action taken by anybody anywhere. If we hadn’t stepped up with the Berlin Airlift and fed the people of Berlin and stood up against the Russians, the map of Europe would be completely different today. Like they say, ‘If you get in trouble, holler. Uncle Sam will come and help you.”

The chaplain’s assistant: Staff Sgt. Michael Doyle

Michael Doyle grew up in the hardscrabble Pennsylvania coal mining town of Mahonoy. With his parents supporting his desire not to end up working in the mines like his father, the day Doyle graduated from high school, he joined the Air Force. Doyle volunteered for what he thought would be six months duty in Germany, which turned into five years.

“I was an assistant to the Catholic priest and a Protestant chaplain,” said Doyle, who served at Erding Air Base near Munich. “And we also had the Rabbi who was chaplain up in Wiesbaden come down and see us all the time. It was all faiths.” One of his tasks, Doyle recalls, was dealing with mothers who would write complaining their sons weren’t writing them letters. “So, I would call the kids in and say, ‘Hey, you better write to your mom!’”

Doyle marveled at the busy pace of activity at Erding, prompted by the Air Base receiving transport aircraft to maintain the airlift. “There was never a day that didn’t go by that people came in from all over the world, because we needed the planes, and they’d send these big cargo planes from all over—Hawaii, Australia, New Zealand, Turkey…and a lot of them had to come to our base because there was only so much maintenance they could do up at Wiesbaden or Frankfurt,” Doyle said. “Our crew chiefs were working day and night. Everybody just assumed that’s what we had to do.”

Today, when you call Michael Doyle, his phone rings to the tune of the Air Force song,nd he still brims with pride about his time in Germany. “I loved the people over there,” he said. “They show their thankfulness and gratitude for our doing what we did. And they knew the Americans were there to stay. We flew food to them, flying in there day and night, even in the fog. I remember the statement ‘you can’t see your hand in front of your face,’ it was that bad. But our pilots never gave up. I will truly go to my grave thinking we really stopped World War III from happening. America stuck it out. I’m one proud SOB. I really, truly mean that.”

See also: