Global instability is one of the defining issues of our time, and its implications are hard to overstate. As instability spreads, extremists and terrorists are finding sanctuary in ungoverned spaces. Energy supplies are being disrupted. Political reform is suffering as too many governments opt for authoritarian measures at the expense of democratic principles and respect for human rights.

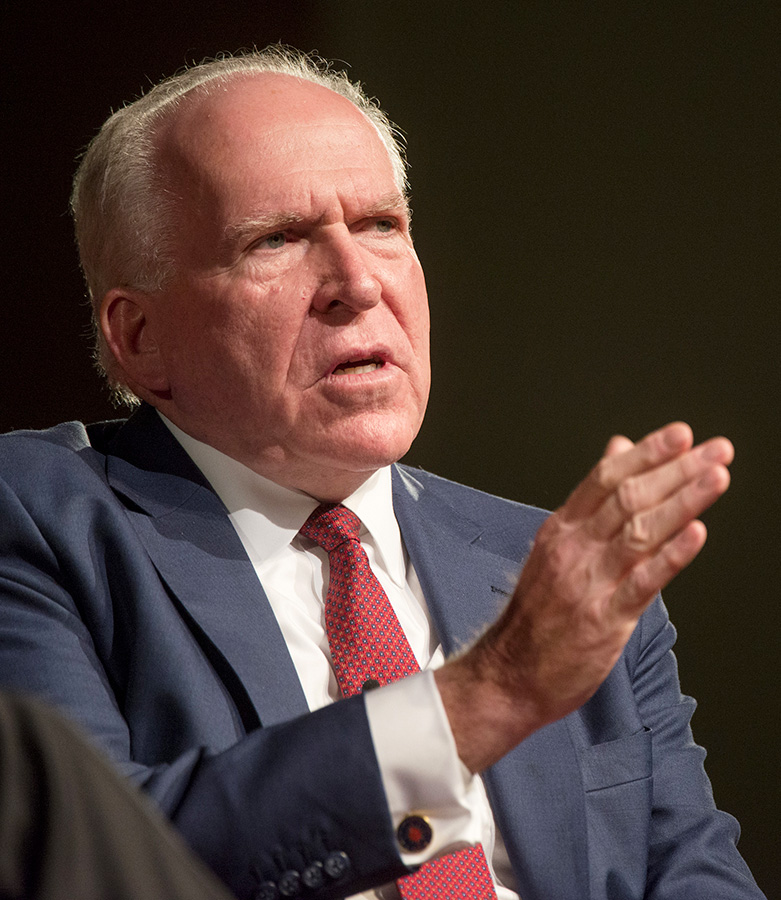

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery by Central Intelligence Agency Director John O. Brennan at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington, DC, 29 June 2016. Source : CIA.

It is indeed a pleasure to be back at the Council to compare notes on a remarkably complex and dynamic international scene. I very much look forward to talking with Judy and Council membership on the many topics that are in the headlines, but I will first offer some brief opening remarks to kick off our conversation.

Whenever I administer the oath of office to new officers at our Headquarters in Langley, Virginia, I tell them that they are coming aboard at a critical moment in our Agency’s history. In the 36 years since I first entered government, I have never seen a time with such a daunting array of challenges to our Nation’s security. Notable among those challenges is that some of the institutions and relationships that have been pillars of the post-Cold War international system are under serious stress.

As you well know, the United Kingdom voted last week to leave the European Union. Of all the crises the EU has faced in recent years, the UK vote to leave the EU may well be its greatest challenge. BREXIT is pushing the EU into a period of introspection that will pervade virtually everything the EU does in the coming weeks, months, and even years. Euroskeptics around Europe—including in Denmark, France, Italy, and the Netherlands—are demanding their own referendums on multiple EU issues; this will surely make decision making and forging consensus in the EU much harder.

No member state has ever left the Union, so Europe is entering a period of uncertainty as the UK and EU take stock of the situation and begin staking out their negotiating positions. Discussions about how an exit will work will dominate the EU agenda in the months ahead. Negotiations for the exit agreement will not begin until the Prime Minister formally notifies the EU of the UK’s intention to leave, which Prime Minister David Cameron has said will occur under his successor. EU and member-state leaders—excluding the UK—will be meeting in the coming days and weeks to begin laying the groundwork for negotiations.

Regardless of what lies ahead, I would like to take this opportunity to say that the BREXIT vote will not adversely affect the intelligence partnership between the United States and the United Kingdom in the months and years ahead. Indeed, I spoke to my counterpart in London early Monday morning, and we reaffirmed to one another that the bonds of friendship and cooperation between our services are only destined to grow stronger in the years ahead. These ties are—and will always be—essential to our collective security.

I presume a few of you have questions about terrorism and the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, and I look forward to addressing them in the question and answer session. I know that our collective hearts go out to the families of the victims of the horrific terrorist attacks perpetrated as well as incited by ISIL; the despicable attack at Istanbul’s International Airport yesterday that killed dozens and injured many more certainly bears the hallmarks of ISIL’s depravity.

Let me take a few moments to say a few words about some less discussed but still very important issues that we at CIA and our colleagues throughout the Intelligence Community are watching closely.

I’ll start with the overarching challenge of instability, which continues to grip large sections of the globe.

Global instability is one of the defining issues of our time, and its implications are hard to overstate. As instability spreads, extremists and terrorists are finding sanctuary in ungoverned spaces. Energy supplies are being disrupted. Political reform is suffering as too many governments opt for authoritarian measures at the expense of democratic principles and respect for human rights.

Most devastating of all is the human toll attendant to instability. Last week, the United Nations reported that the number of people displaced by global instability and conflict had reached 65 million—the highest figure ever recorded.

In a host of countries, from East Asia to the Middle East to West Africa, governments are under stress, and civic institutions are struggling to provide basic services and to maintain law and order. As governments in these regions recede from the center of national life, more people are shifting their allegiances away from the nation state and toward sub-national groups, leading societies that once embraced a national identity to fracture along ethnic and sectarian lines.

Nowhere is this trend more evident than in the Middle East, a region I have studied closely for much of my professional life. When I lived there years ago, I liked to walk through neighborhoods and villages to observe the rhythms of everyday life. I remember seeing people of different backgrounds and beliefs living side by side, secular and devout.

Today, relations among these groups are too often marred by suspicion and distrust and even outright hostility. Extremist groups have played a key role in fueling these tensions, luring impressionable young men and women to join their cause, and spreading false narratives meant to divide and inflame.

In some areas, a whole generation is growing up in an environment of militarism, without a chance to develop the skills to contribute to or even to engage in modern-day society.

The underlying causes of these trends are complex and difficult to address and the long-term consequences of these developments are deeply troubling. Global instability is an issue that affects all countries, from Russia to China to the United States, and it must be met by a strong, collective response from the international community. I am certain it will loom large on the agenda of the next Administration.

Another strategic challenge is dealing with the tremendous power, potential, opportunities, and risks resident in the digital domain. No matter how many geopolitical crises are seizing the headlines, the reliability, security, vulnerability, and range of human activity taking place within cyber space are constantly on my mind.

On the cyber security front, organizations of all kinds are under constant attack from a range of actors…foreign governments, criminal gangs, extremist groups, “cyber activists,” and many others. In this new and relatively uncharted frontier, speed and agility are king. Malicious actors have shown they can penetrate a network and withdraw in very short order, plundering systems without anyone knowing they were there until maybe after the damage is done.

While I served at the White House, cyber was part of my portfolio, and it was always the subject that gave me the biggest headache. Cyber attackers are determined and adaptive. They often collaborate and share expertise. And they come at you in so many different ways, with an ever-changing array of tools, tactics, and techniques.

John O. Brennan – Photo Jay Godwin

Moreover, our laws have not yet adequately adapted to the emergence of this new digital frontier. Most worrisome, from my perspective, is that there is still no political or national consensus on the appropriate role of the government—law enforcement, homeland security, and intelligence agencies—in safeguarding the security, reliability, resiliency, and prosperity of the digital domain.

The Intelligence Community is making great strides in countering cyber threats, but much work remains to be done. As we move forward on this issue, one thing we know is that private industry will have a huge role to play, as the vast majority of the internet is in private hands. Protecting it is not something the government can do on its own.

Right up there with terrorism, global instability, and cyber security is nuclear proliferation and the accompanying development of delivery systems—both tactical and strategic—that make all too real the potential for a nuclear event. Unsurprisingly, top on my list of countries of concern is North Korea, whose authoritarian and brutal leader has wantonly pursued a nuclear weapons program to threaten regional states and the United States instead of taking care of the impoverished and politically repressed men, women, and children of North Korea.

* * * *

So what else is there besides terrorism, global instability, cyber security, and nuclear proliferation that worries the CIA Director and keeps CIA officers busy around the clock and around the globe?

Well, as a liberal arts guy from the baby boomer generation, the rapid pace of technological change during my lifetime has been simply dizzying. Moreover, as we have seen with just about every scientific leap forward, new technologies often carry substantial risks to the same degree that they hold tremendous promise.

Nowhere are the stakes higher for our national security than in the field of biotechnology. Recent advances in genome-editing that offer great potential for breakthroughs in public health are also cause for concern, because the same methods could be used to create genetically-engineered biological warfare agents. And though the overwhelming majority of nation states have tended to be rational enough to refrain from unleashing a menace with such unpredictable consequences, a subnational terrorist entity such as ISIL would have few compunctions in wielding such a weapon.

The scope of the bio threat—as well as potential measures to mitigate it—were laid out very clearly last October in the bipartisan report of the Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense, chaired by former Senator Joe Lieberman and former Homeland Defense Secretary Tom Ridge. As with the cyber threat, the international community’s response to this issue lags behind the technology driving it. Effectively countering this danger requires the development of national and international strategies, along with a consensus on the laws, standards, and authorities that will be needed.

And as CIA officers and their Intelligence Community colleagues work hard to protect our country from the darker side of technological change, we are mindful of how even beneficial advances can have destabilizing effects in the long run. Agency all-source analysts, drawing from academic studies and other elements of the ever-expanding pool of global open-source information, seek to offer our national leaders early warning of potential challenges that could arise from the advances we are seeing today across the spectrum of technological endeavors.

As former Defense Secretary and CIA Director Bob Gates is fond of saying, “When intelligence officers smell flowers, they look around for a coffin.” That remains a pretty good depiction of our intelligence mindset.

One example—again taking a page from the biotech and life-sciences sectors—is how a wide range of breakthroughs that potentially could extend life expectancy, such as new methods of fighting cancer and a greater understanding of the ageing process, could reinforce the trend toward older populations in advanced nations. Some of the world’s leading economies could face stronger headwinds from having significantly larger proportions of retired people relative to working-age citizens.

Another example is the array of technologies—often referred to collectively as geoengineering—that potentially could help reverse the warming effects of global climate change. One that has gained my personal attention is stratospheric aerosol injection, or SAI, a method of seeding the stratosphere with particles that can help reflect the sun’s heat, in much the same way that volcanic eruptions do.

An SAI program could limit global temperature increases, reducing some risks associated with higher temperatures and providing the world economy additional time to transition from fossil fuels. The process is also relatively inexpensive—the National Research Council estimates that a fully deployed SAI program would cost about $10 billion yearly.

As promising as it may be, moving forward on SAI would raise a number of challenges for our government and for the international community. On the technical side, greenhouse gas emission reductions would still have to accompany SAI to address other climate change effects, such as ocean acidification, because SAI alone would not remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

On the geopolitical side, the technology’s potential to alter weather patterns and benefit certain regions at the expense of others could trigger sharp opposition by some nations. Others might seize on SAI’s benefits and back away from their commitment to carbon dioxide reductions. And, as with other breakthrough technologies, global norms and standards are lacking to guide the deployment and implementation of SAI.

I could go on, and on, and on, but rather than talk about the things that I find fascinating, let me stop here so that Judy and I can have a conversation and then I can take some of your questions. Again, thank you for inviting me back to the Council and thank you for your continued interest in our country’s foreign relations and national security.

Related Topic :