The quality of the comments and questions raised during the hearing of Major General Aymeric Bonnemaison, COMCYBER, by the National Defence and Armed Forces Committee on 7 December 2022 and then during his press conference on 12 January 2022, illustrate the interest mixed with concern that an increasingly digitalised and cyber-dependent society has for a field that is both rich in promises and threats.

by Major General Jean-Marc Wasielewski (FR-Army retd) [*] — 15 February 2023 —

Table of Contents

The article « Until when can we avoid a cyber disaster? » published in Le Figaro on 7 February is reminiscent of the warning issued by the US Secretary of State for Defence Leon Panetta in 2012 when he spoke of « Cyber Pearl Harbor »[1] and listed similar scenarios.

Following Russia’s cyber » achievements « , especially against Estonia and Georgia, many thought that Ukraine would succumb to the attacks of Russian hackers, be they privateers or pirates. It turns out that the “cyber blitzkrieg” did not happen because of a particularly efficient Ukrainian defence in depth. However, it is possible that Russia has not deployed its full cyber arsenal and that it may have some strategic surprises in store for Ukraine, but also for its allies.

In 1992, General Monchal, then Chief of Staff of the French Army, declared « in the future, the master of the electron will prevail over the master of fire ». It is clear that in Ukraine, the master of fire does not give way to the master of the electron and that, if in war 2.0 information – in all its forms – is a weapon, it is most often fire that is decisive.

The fact remains that kinetic actions are supported by cyber-electronic actions to achieve strategic, operational or tactical objectives; that there is a real complementarity between cyber and electronic warfare; that the massive use of mobile phones equipped with innovative applications, drones and « intelligent » munitions could, if not reshape the digital battlefield, at least modify the doctrines of command, control and intelligence.

The information disseminated by the COMCYBER, in particular that contained in the minutes of his hearing, describes the context and the operations carried out by the belligerents with sufficient precision and concision. The purpose of this document is not to comment on his statements but, based on the use of open information – mostly Anglo-Saxon – to propose some additional avenues for reflection on the use of cyber-electronics in Ukraine.

1. About cyber-electronics

« For the past decade, the return of a major war has structured the thinking of the leading military powers. In order to win, it will be necessary in a classical strategic logic to produce decisive effects through manoeuvre. However, the latter will have to accommodate two variables: operational mastery of the second age of digital technologies (AI, robotics, etc.) and the ability to overcome the new forms of attrition resulting from the multiplication of adversary capabilities of denial of access and indirect action in depth. A doctrinal overhaul among the major powers is therefore underway, led by the United States and Russia, to determine the ways and means necessary to restore freedom of action. (…)

Russian and American doctrines of future operations converge on the nature of the manoeuvre envisioned, which should be a synergy of domains. In order to overcome the Anti-Access/Area Denial capabilities, which are constantly reinforced by technological progress, it is necessary to create operational dilemmas for the adversary, saturating his reaction capabilities by integrating the areas of combat in depth. However, in a strategic context of major confrontation, the nuclear factor remains critical, which means that in reality these synergistic operations lead to a return to « limited warfare », since it is a question of obtaining effects while containing the risks of escalation so as not to reach the nuclear threshold. (…)

This doctrinal vision is matched by a similar capability plan for these two states in the use of second-generation digital technologies. Within this framework, a general cybernetisation of action is envisaged (AI, autonomous systems, global communications) as well as a development of the means of in-depth action (extension of the ranges of indirect fire, hardening of the means of projection). »[2]

Russia had successfully put some or all of these principles into practice in Georgia in 2008 and in the Donbas in 2014. From the application of these principles, we shall retain in particular the convergence between actions in cyberspace and those conducted in the electromagnetic spectrum, which the US Army expresses in its concept of « cyber-electronic activities ».

« Cyber electromagnetic activities (CEMA) are activities leveraged to seize, retain, and exploit an advantage over adversaries and enemies in both cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum, while simultaneously denying and degrading adversary and enemy use of the same and protecting the mission command system. CEMA consist of cyberspace operations, electronic warfare, and spectrum management operations »[3]

This definition can be applied to both current belligerents because, while the Soviet armies had a wide range of electronic warfare capabilities down to the lowest tactical level, it appears that today’s forces have just as many.

« Starting in 2014, while NATO countries had abandoned́ their electronic warfare (EW) capabilities, they became aware, that other countries like Russia had developed́ theirs. Moscow has made it a major asset in a new form of warfare for which our countries no longer seem prepared (…) The use of Russian EW in support of separatist forces has surprised not only the Ukrainian military but also Western observers. The Russian EW has made the following contributions:

- Protection of friendly forces by decoying missiles, jamming guidance systems or causing premature detonation of munitions;

- Target acquisition by locating enemy command posts;

- Jamming enemy communications to fix them before artillery strikes;

- Disrupting navigation systems such as GPS;

- Jamming drone links to prevent their use; – supporting information operations, in particular by broadcasting personalised SMS messages in order to destabilise their adversaries or encourage them to broadcast to reveal their position.[4]

« From mid-2014 to early 2015, Russian and Ukrainian troops clashed in the Donbas, and the latter suffered several severe defeats. One of the keys to Russia’s success was the initial superiority of its ‘reconnaissance-firepower’ combination of reconnaissance drones, electronic warfare and communications equipment and artillery batteries. This combination allowed them to drown enemy positions or units in a deluge of fire within fifteen minutes of their detection, with the consequence that 80 per cent of Ukrainian losses during the period were caused by Russian artillery.»[5]

These observations are relevant today.

Finally, as General Bonnemaison points out, « the Russians have for a long time integrated the cyber manoeuvre and the informational manoeuvre, by strongly linking the two in their action. They cover both the content and the container in their approach.»[6]

British academic Keir Giles gives a much more comprehensive definition of the concept of « information warfare » :

« For Russia, “information confrontation” or “information war” is a broad and inclusive concept covering a wide range of different activities. It covers hostile activities using information as a tool, or a target, or a domain of operations. Consequently, the concept carries within it computer network operations alongside disciplines such as psychological operations, strategic communications, influence, along with intelligence, counterintelligence, “maskirovka”, disinformation, electronic warfare, debilitation of communications, degradation of navigation support, psychological pressure, and destruction of enemy computer capabilities. Taken together, this forms a whole of systems, methods, and tasks to influence the perception and behavior of the enemy, population, and international community on all levels.»[7]

2. About the use of Cyberwarfare

However, if the use of cyber-electronic weapons has increased the fog of the hybrid war that the Russian armies have been waging in Ukraine for a year, it has not been as thick as they would have liked. Indeed, while it is possible to analyze the consequences of the various cyber-actions carried out before the outbreak of hostilities, it is difficult to measure their real effectiveness since the beginning of the offensive – both in terms of the destruction of targets and the quality of their overall support.

« Though cyberwarfare has been a hard-fought and important part of a conflict that has acted as a testing ground for this still-novel form of battle, it does not seem to have been the killer app, as it were, that some expected.»[8]

« We in the military tend to attribute to cyber warfare a major role in the conflicts of the future. However, in this particular conflict, cyber did not do everything, despite the initial Russian domination. When gunpowder talks, offensive cyber warfare finds its limits. In the preliminary phase of the war as in its intensive phase, cyber sabotage actions were attenuated in favour of a classic war that was much more lethal, kinetic and brutal. It is tempting to develop a somewhat romantic view that everything will be done in the future in a virtual world, but the reality is that it is necessary to take into account all aspects of a conflict.»[9]

There are several explanations for what appears to be the underperformance of the Russian armed forces.[10]

a. Overestimation of the capabilities of the Russian armed forces and underestimation of the difficulty of waging war in the aether

In 2017, Nicolas Mazzuchi already questioned the real potential of Russia in the cyber domain:

« How could this country which seemed, not long ago, far from the level of the United States and China have become in a few years the main global cyber aggressor? This vision of an awakening of the Russian cyber bear, using the Net to carry out actions with a geopolitical aim, must be weighed against the realitý of the national technical and economic potentials as much as with the strategic aims of a country whose priorities remain oriented towards its ‘near abroad (…) »

and further

« Before 2013-2014, Russian hackers appeared to be of a good standard, but unable to achieve the critical mass necessary to form a unified and organised body, the building block of a respectable cyber force. So what happened in the course of a few years to bring about such a dramatic change, giving rise to sometimes exaggerated fears during the US and French presidential elections or the British Brexit referendum? »[11]

« Before 2013-2014, Russian hackers appeared to be of a good standard, but unable to achieve the critical mass necessary to form a unified and organised body, the building block of a respectable cyber force. So what happened in the course of a few years to bring about such a dramatic change, giving rise to sometimes exaggerated fears during the US and French presidential elections or the British Brexit referendum? »

« Most of the attacks (2022) have been attributed by Ukrainian and Western sources to Russian government entities— chiefly the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence service, which has a history of using disruptive cyberattacks. In a few cases, proxy groups (such as the leading ransomware group Conti) were also involved, and in one reported instance, a Brazilian hacker group supportive of Russia attacked Ukrainian universities. All these hacking efforts, whether by the GRU or not, seem to have been poorly coordinated with Russian military actions in Ukraine.»[12]

« Some Western spies thus say the war shows a gulf between American and Russian proficiency in high-end cyber-operations against military hardware. But others warn that it is too early to draw sweeping conclusions. Russia’s cyber-campaign may have been constrained less by incapacity than by the hubris that also afflicted its conventional armed forces. »[13]

Hence, Russia is said to have sinned both by pride and by excessive optimism in its skills, which led it to underestimate the resistance capabilities of its adversary and, consequently, to neglect the preparation of an elaborate plan for large-scale cyber-attacks, voracious in terms of both time and resource mobilisation.

The conduct and coordination of combined tactical actions on land and in cyberspace is particularly complex, especially when there is friction. « Matching the speed of cyberspace operations with the speed on the battlefield is a challenge. However, in the Russian plan, the lightning speed of conventional action – a few days to bring down Kiev – was to allow ground forces to capitalise on the effects generated in cyberspace. Thus, by 24 February, Russia’s main geographic targets were losing connectivity. It was also at this time that the AcidRain malware/wiper paralysed the modems of the Viasat satellite communication network, which was used by the Ukrainian armies in particular. Yet the slow pace of the ground advance will not allow this advantage to be properly capitalised upon and will allow the Ukrainian forces to find workarounds, restore sufficient connectivity and prevent the blackout.»[14]

« American, European and Ukrainian officials all say that there are many examples of Russian cyber-attacks synchronised with physical attacks, suggesting a degree of co-ordination between the two branches. But there have also been clumsy errors. In some cases, Russian military strikes took down the same networks that Russian cyber-forces were attempting to infect—ironically forcing the Ukrainians to revert to more secure means of communication.»[15]

« The failure (so far) to disrupt Ukrainian operations, logistics, and communications probably reflects the haphazard nature of Russian planning, flawed assumptions about the reception Russian forces would receive, and the strength of the Ukrainian cyber defenses.»[16]

The same applies to offensive electronic warfare, which is certainly effective against Ukrainian drones and smartphones, but for which there have been many cases of fratricide jamming (on both sides) due to the intermingling of highly digitised units, whether with military or civilian equipment, and dependent on the same electromagnetic spectrum.

« While Russian troops also have been reportedly using cell phones and even stealing SIM cards which means the Russians are probably reliant on the local Ukrainian communication infrastructure suggesting a lack of their own resilient or redundant communications.

Therefore, another possible explanation is that Russians are not using jammers to not disrupt their battlefield communications because even if jamming can be effective at blocking enemy communications, it can also interfere with friendly communications if not done properly indicating that Russian forces lack proper tactics for warfare in EMS (Electro Magnetic Spectrum) domain that needs good electromagnetic management.

This has been observed not just for communication networks but also in the case of satellite navigation signals where the Russian Armed Forces have experienced “electronic fratricide” because of their jamming actions.»[17]

This observation applies to EW equipment on some aircraft.

« (…) Fratricide is a systemic issue between Russian systems. For example, the Khibiny EW pod, mounted to a number of Russian aircraft, automatically detects radars and disrupts them. Unfortunately for the Russians, it tends to also do this to other Russian aircraft. Pairs of Russian strike aircraft mounting this system have therefore had to choose between having a functional radar or EW protection. They have often been ordered to prioritise their radar. (…)»[18]

Furthermore, eavesdropping and tracking pose a permanent threat.

« Electronic eavesdropping pervaded the frontline of the War in Donbas, and the relevant equipment was used by both the Ukrainian and separatist/Russian units. Walkie-talkies, mobile phones and even radio stations were monitored, and commanding officers tended to discuss issues that matter in person whenever possible.»[19]

« Russian communications were inadequately secured (…) While Russia’s special operations forces have access to sophisticated tactical communications gear using strong encryption (judging from earlier operations in Ukraine), these were in short supply for other units in this invasion. Some Russian units relied on inadequately secured mass-market Chinese equipment. Others relied on Ukraine’s commercial telecommunication infrastructure. This reliance creates two major difficulties. First, when the Russians destroyed Ukrainian telecommunications infrastructure, whether inadvertently or intentionally, this hampered their own communications. Second, relying on an opponent’s communications system creates numerous possibilities for exploitation. Many speculate that one reason for the high casualty rate among Russian senior officers was that their vulnerable communications allowed their location to be pinpointed.»[20]

Finally, major cyber-attacks could have had the effect of neutralising infrastructure or destroying databases that the Russians thought they could use in the near future.

« Western officials say that Russia failed to plan and launch highly destructive cyber-attacks on power, energy and transport not because it was unable to do so, but because it assumed it would soon occupy Ukraine and inherit that infrastructure. Why destroy what you will soon need? When the war dragged on instead, it had to adapt. But cyber-weapons are not like physical ones that can simply be wheeled around to point at another target and replenished with ammunition. Rather, they have to be tailored specifically to particular targets.»[21]

In December 2022, Jon Bateman drew the following lessons from Russian cyberwarfare operations:

- « Russian cyber “fires” (disruptive or destructive attacks) may have contributed modestly to Moscow’s initial invasion, but since then they have inflicted negligible damage on Ukrainian targets.

- Cyber fires have neither added meaningfully to Russia’s kinetic firepower nor performed special functions distinct from those of kinetic weapons. Rather than serving in a niche role, many Russian cyber fires have targeted the same categories of Ukrainian systems also prosecuted by kinetic weapons—such as communications, electricity, and transportation infrastructure. For almost all these target categories, kinetic fires seem to have caused multiple orders of magnitude more damage.

- Intelligence collection—not fires—has likely been the main focus of Russia’s wartime cyber operations in Ukraine, yet this too has yielded little military benefit.

While many factors have constrained Moscow’s cyber effectiveness, perhaps the most important are inadequate Russian cyber capacity, weaknesses in Russia’s non-cyber institutions, and exceptional defensive efforts by Ukraine and its partners.»[22]

b. The effectiveness of Ukrainian cyber defence

« Renowned for its engineering training, Ukraine had become one of the world’s leading offshore IT centres in recent decades. Some saw it as the European capital of the profession, renamed « near-shore » because of its cultural and time proximity to the end clients.(…) The country employs tens of thousands of IT specialists on behalf of service companies that are themselves commissioned by groups such as Deutsche Bank, IBM or the international telecommunications operator Lebara.»[23]

The 2014 invasion and the quality of Russian cyber-attacks had led Ukraine to strengthen the protection of its IT systems, to develop data backup plans by extending cloud computing and to generalise the dispersion of sensitive data, especially across borders.

Between 2014 and 2022, Ukraine has put in place a robust cyber defence policy. « Ukraine published a national cybersecurity strategy in 2016 and established a degree of redundancy and resilience for data and expanding the use of encryption before the invasion. It implemented some basic cyber “hygiene” measures after 2015. Cyber hygiene before an attack is important, but the most important element of defense is the ability to identify and react quickly.

Ukraine (with external assistance) undertook real-time monitoring of critical networks and systems to detect exploits early on and then act quickly to counter them (…) Ukraine reportedly used a third-party hosting arrangement to move some data and services outside of the geographic boundaries of the conflict. If nothing else, this complicated and constrained Russian planning.»[24]

Ukrainian services played the main role in the defence, but national resources alone would not have been able to contain the 4,500 cyber-attacks they suffered.[25] Ukraine had a network of government and corporate partners who were able to provide training and assistance, including remote monitoring and mitigation, before and after the invasion.

« The arrival of the American personnel tasked with detecting possible pre-positioned software was crucial in the weeks preceding the conflict. Within two weeks, their mission became one of the largest deployments of US Cyber Command, involving more than 40 US armed services personnel. They had a first-hand knowledge of Russia’s escalating cyberspace operations in January, putting Ukrainian systems under unprecedented strain. These teams engaged in a hunting-forward mission, surveying partners’ computer networks for signs of pre-positioning.»[26]

Tech companies have provided valuable assistance. Collective action involving domestic and foreign, governmental and private, gave Ukraine an advantage in monitoring and reacting quickly to block attacks and repair or eliminate vulnerabilities.

« Western assistance was also crucial. In the prelude to war, one way NATO enhanced its co-operation with Ukraine was by granting access to its cyberthreat library, a repository of known malware. Britain provided £6m ($7.3m) of support, including firewalls to block attacks and forensic capabilities to analyse intrusions. The co-operation was mutual. “It is likely that the Ukrainians taught the US and the UK more about Russian cyber-tactics than they learned from them,” notes Marcus Willett, a former head of cyber issues for Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) Ukrainian resilience was helped, paradoxically, by the primitive nature of many of its industrial-control systems—inherited from Soviet days and not yet upgraded.

Private cyber-security companies have also played a prominent role. Mr Zhora (head of Ukraine’s defensive cyber-security agency) singles out Microsoft and ESET, a Slovakian firm, as being particularly important for their large presence on Ukrainian networks and the “telemetry”, or network data, that they collect as a result. Microsoft says that artificial intelligence, which can scan through code more quickly than a human being, has made it easier to detect attacks. On November 3rd Brad Smith, Microsoft’s president, announced that his firm would extend tech support to Ukraine until the end of 2023 free of charge. The pledge brought the value of Microsoft’s support to Ukraine since February to more than $400m.»[27]

3. Information is a weapon, the smartphone is the vector

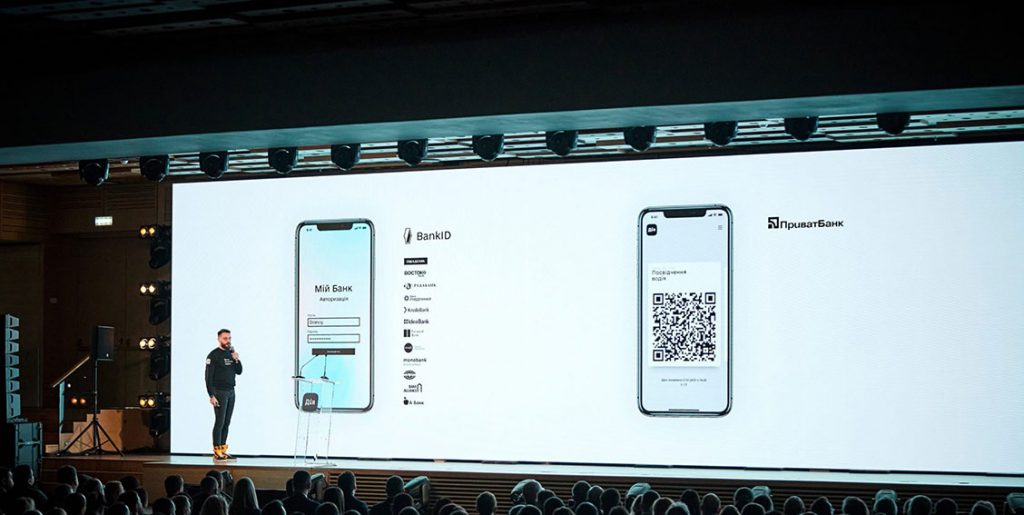

Since his appointment as Minister of Digital Transformation in 2019, Mykhailo Fedorov has had the ambition to make Ukraine a global digital champion (« a digital country »)[28] by launching an ambitious national digitisation plan through a digital offer of public services called Diia. The mobile application, which provides access to, among others, 14 digital documents (identity card, passport, permit, etc.) had been downloaded by more than 18 million Ukrainians by December 2022.

Mykhailo Fedorov — Photo Dubetskyi-Ph

It would appear that this platform and its applications were able to withstand the Russian cyber-attacks and ensure the continuity of public services,[29] as connectivity was maintained thanks to Elon Musk’s provision (free of charge) of the Starlink satellite service, which is much more resistant to jamming than Viasat.

Since the 24th of February 2022, Diia has found a hybrid use by hosting the Delta application, which was quickly developed through the inventiveness and determination of Ukrainian civilian and military developers. In compliance with NATO technical standards,[30] Delta provides a detailed picture of the battle space and allows users to identify friends and enemies, the location and type of particular objects.

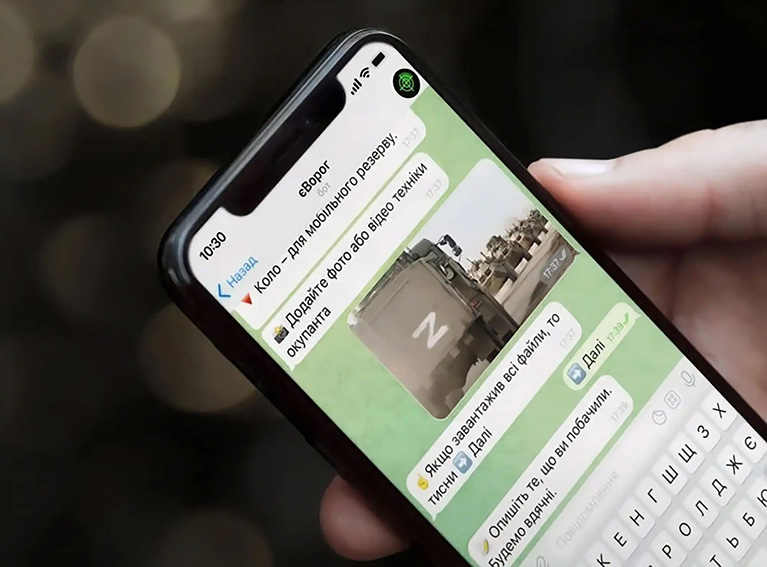

« You can report where the enemy is using the Diia application, » explains Mykhailo Fedorov, adding that « a chatbot, based on geolocalisation, has been created to help citizens know the position of enemy troops.[31]

Russian forces are seeking to seize these phones filled with personal information and are persecuting those who use the application.

Ukrainians are proud of their responsiveness and trust the « master of the electron » to help them win future battles.

« Russia’s current war against Ukraine is considered a network-centric war – the type of military conflict in which one side gains the advantage not because of superiority of its forces and combat assets, but because of more advanced intelligence.

As the NGO Aerorozvidka has pointed out, ‘one of the main concepts of such a war is to gain an information advantage by combining technical intelligence assets and other sources of information into a single network.‘»[32]

Currently, according to the website war.ukraine.ua, the Ukrainian military has a dozen of software and applications installed on smartphones or tablets, including Kropyva (Nettles) (fire support), MilChat (secure messaging), MyGun (ballistic calculator), ComBat Vision (intelligence).

« Ukrainian creativity and initiative are on full display. Training on US artillery, Ukrainians supplement instruction and then battlefield deployment with a smartphone app that assists with calculating targeting information. The app, created by a Ukrainian civilian working with the military, helps artillery units quickly compute firing information by inputting information such as environmental conditions, distances and charges – a game-changer in artillery duels with Russian forces. This is one of many examples that demonstrate a military organisation capable of incorporating human capital in ways that tap ingenuity and knowledge of the details of combat challenges while preserving chains of command – a stark contrast to Russian military culture and practice.»[33]

« The principle has already been used in previous conflicts. The Ukrainian genius lies in having changed scale by relying on the very high degree of digitisation of its population and by mobilising its ecosystem of developers. Every soldier, every citizen is now a « digital combatant ». Armed with their smartphone, each person becomes a link in an accelerated, reduced and fluid decision-making loop and an actor in the achievement of a central objective, that of « striking first » « The Ukrainians exploited all this perfectly », said a French soldier. And, above all, they quickly realised that Russia was lagging behind in this segment with « very classic military communications that did not work ». For want of anything better, the Russian soldiers fell back on unsecured equipment in an anarchic manner, making it extremely easy to target them.»[34]

4. Towards a transformation of the digitised battle space ?

The use of smartphones is not only changing the face of combat in Ukraine, but could revolutionise the concepts of computerisation in Western armies. « The omnipresence of mobiles on the battlefield creates a set of unique participatory media practices. A variety of personal purposes, such as private communication and entertainment, are combined in the same device with wiretapping, fire targeting, minefield mapping and combat communication. Mobiles supplant old or unavailable equipment and fill gaps in military infrastructure, becoming weaponized and contributing to the hybridization of the military and the intimate, and of war and peace. These results imply the role of mobiles as a mediated extension of battlefield and question the very definition of what constitutes weapon as tool of combat.»[35]

However, it has to be said that the smartphone can quickly show the drawbacks of its merits if it is used without rules or discipline, both in terms of its electromagnetic and light emissions or because it is not, as in most cases, encrypted. « A more routine situation is when artillery targets many mobile numbers that simultaneously become active in an unexpected place, such as in the middle of a field or wilderness. Tracing this requires access to base stations, which is often unproblematic at the digitally porous frontline. One informant told me it is even possible to calculate the unit’s strength by weighing the number of active phones (…)»[36]

Moreover, this multi-media combat tool, which can be used to call your children and then, without transition, to neutralise your enemies, has a purpose that turns every combatant into a war journalist, capable, among other things, of photographing prisoners and the killed, identifying them on social networks thanks to artificial intelligence (Clearview AI) and then sending the pictures to their families. We are entering a new and unprecedented dimension of information warfare.[37]

Major General Jean-Marc Wasielewski (FR-Army retd) — Photo © DR —

5. Comments

« (…) this war is being waged at a pace set by civilian digital technology. This has already been the case in the Sahel, where adversaries have little access to military-class technology and rely on civilian technologies to communicate and conduct information-based attacks.»[38]

Thanks to the hybridisation of civilian and military technologies, the complementarity of the public and private know-how of the computer and satellite communications giants, it did not take long for the Ukrainians to develop several applications equivalent to the « blue force tracking » and to set up an intelligence / OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) loop that was particularly effective and easy to use, whereas the western defence industries struggled to develop identical software on purely military equipment that was much less user-friendly.

The swiftness of the decision cycle, the accuracy and speed of transmission of intelligence – technical or man-made, coupled with the use of armed drones and « smart » munitions has devastating effects on command posts and logistics bases. As the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) wrote in its feedback to the UK Ministry of Defence: « There is no sanctuary ».

Survival is now linked to dispersion and an agile and reactive command and control organisation.

« The historical approach of the Allied Rapid Reaction Corps and 3 UK Division of erecting tented cities – command posts with a large physical footprint – is non-viable in wartime on the modern battlefield. These sites will be identified and struck. Moreover, as the Russians have found to their detriment, concentrated command posts inside requisitioned civilian buildings are similarly vulnerable to long-range precision fires unless all staff retain rigid communications discipline. Even here, the HUMINT threat means that locations should be moved frequently and key components of a staff dispersed. The capacity to access staff work remotely means that it is not strictly necessary to concentrate all headquarters components in close physical proximity to one another.»[39]

However, at present we have no information on:

- The techniques for verifying, merging and managing the large flows of data from countless sensors

- The organisation of collaborative, distributed and delocalised work

- The organisation and running of headquarters and command post (CP) systems;

- The planning of operations and the decision-making process;

- The dissemination of orders and the media used to do so – although Starlink offers a high quality internet service, reassuring redundancy and resilience.

Nor do we have any feedback on the frequency and quality of Ukrainian cyber actions carried out to complement or support operations, nor on the nature and volume of intelligence acquired on Russian forces, apart from the unenthusiastic comment by James A. Lewis of the Center for Strategic & International Studies, which, however, only refers to hackers:

« While celebrated in the media, the various cyber actions against Russian websites by private actors had no effect on Russian military operations, its military capabilities, or, as far as anyone can tell, Putin’s strategic calculations. The results of the activities of “hacktivists” and their efforts against Russia are exaggerated. Russia did not change course or alter plans as a result of these hacktivist efforts, nor was the Russian capability to engage in offensive operations, spotty as it may have been, degraded by hacktivist action. Russian public opinion, largely supportive of the war, seems unaffected by hacktivism. By these measures, hacktivism is irrelevant to the course of the war.»[40]

6. Conclusion

As early as 2014, when they were wondering whether cyberwar would take place, Colonels Bonnemaison and Dossé were already drawing the following conclusions: « Cyber-electronic warfare is therefore no more and no less than an additional means of action that interacts off and on the battlefield. It does not revolutionise strategy or operational art, whose principles remain. Cyberspace affects the tactical field with its own dynamics, but it can only be effective in the context of a joint, combined or global manoeuvre. In all cases, it contributes to the fundamentals of combat, i.e. to constrain an adversary, to control the environment and to influence perceptions. While its action is generally not decisive, any failure in this area will result in a defeat.»[41]

With the experience of the operations that have just taken place, James A. Lewis says it all:

« In conflicts involving modern militaries, cyberattacks are best used in combination with electronic warfare (EW), disinformation campaigns, antisatellite attacks, and precision-guided munitions. The objective is to degrade informational advantage and intangible assets (such as data), communications, intelligence assets, and weapons systems to produce operational advantage. The most damaging actions would combine precision-guided munitions and cyberattacks to disable or destroy critical targets. Cyber operations can also be used for political effect by disrupting finance, energy, transportation, and government services to overwhelm defenders’ decision-making and create social turmoil. Russia has been unable to achieve any of these objectives at meaningful scale. It takes real effort to make a cyberattack more than a dramatic annoyance. This requires planning, tool development, and reconnaissance, integrated with other offensive capabilities. The test of effectiveness lies in the results, measured by the extent of damage and whether the cyber operation forced an opponent to change plans or make concessions. Also, unlike a successful attack using a kinetic weapon, cyberattacks do not assure destruction (a radar hit by a missile can be seen to be a smoking ruin, but from the outside, a successful cyberattack on a radar may not look different from one that fails, and any damage may not be permanent).»[42]

His assessment of Russian shortcomings is unambiguous:

« Russia has shown how not to use cyber operations to gain advantage in armed conflict, but its efforts highlight best practices. The most obvious lesson is the need for adequate preparation to generate coordinated, simultaneous strikes on critical targets. The second is to achieve cyber superiority by crippling cyber defenders. The third is to prepare the battlefield politically and psychologically and to control the public narrative of the campaign as much as possible.»[43]

However, as James A. Lewis points out, the damage caused by cyber operations is difficult to assess. According to Jon Bateman,[44] the Ukrainians have an interest in minimising the scope and suppressing evidence of any cyber disruption of military equipment; the Russians seek to hide their shortcomings and put the effects of cyber disruptions on third parties into the shade; and allies have commercial interests in presenting their cyber support to Ukraine as highly successful and strategically essential.

Deciding on these debates and drawing lessons from them will take time and hindsight, as many intrusions may have gone unnoticed. Ultimately, a « fog of cyber war » continues to envelop even the most closely monitored cyber incidents.

That said, even if Ukraine and its allies have shown that in the cyber domain, well-organised defence in depth is superior to attack, this remark by James A. Lewis might seem excessive:

« It may offend the cyber community to say it, but cyberattacks are overrated. While invaluable for espionage and crime, they are far from decisive in armed conflict. A pure cyberattack, as most analysts note, is inadequate to compel any but the most fragile opponent to accept defeat. »

While his comment applies to armed conflict, so far the most sophisticated cyber-attacks take place in peacetime, as Stuxnet showed in 2010.

« The origin of this offensive is not officially known (…) Many analysts suppose that it was a joint operation. Whatever the case, its originality lies in the fact that it militarises a cyber-crime process to transform it into a strategic mode of action, in the depth of the enemy’s system. It thus adds to clandestine commando operations and air raids the possibility of a subtle strategy of sabotage through a discreet, effective and potentially unsigned action»…[45] Therefore without possible use of Article 5 or Article 42.7.

As a consequence, everything is still possible in terms of aggression, especially since we have certainly not experienced everything yet:

« Russia is almost certainly capable of cyber-attacks of greater scale and consequence than events in Ukraine would have one believe,” The war “has not yet involved both sides using top-end offensive cyber-capabilities against each other ».[46]

Last but not least, there is a potential top-ranking adversary that must not miss a beat in the ongoing operations, be they cyber or conventional: China. « The conflict in Ukraine can inform the United States and its allies on how to defend against offensive cyber operations directed against it by opponents, but China or even Iran may have also learned from the Russian experience. For cyber actions, Ukraine is probably not a safe precedent for conflict with any possible attack by China. China is better equipped and likely to have better planning. The United States may also not want to count on ineptitude among these opponents, even if they share authoritarian (and thus potentially idiosyncratic) decision-making.»[47]

Jean-Marc Wasielewski

————-

[1] « U.S. Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta warns of dire threat of cyberattack » on U.S. in New York Times, 11 October 2012. « The most destructive possibilities, Panetta said, involve « cyber actors launching multiple attacks on our critical infrastructure at the same time, in combination with a physical attack. « He described the collective outcome as a « cyber-Pearl Harbor that would cause physical destruction and loss of life, an attack that would cripple and shock the nation and create a profound new sense of vulnerability ».

[2] Thibault Fouillet in « La vision stratégique de l’Armée de terre », Les cahiers de la Revue de la Défense Nationale, 2020 —

[3] Field Manual 3-38 Cyberelectromagnetic activities, 2014 — Of the six branches of the U.S. armed forces only the U.S. Army uses CEMA as a doctrinal concept to distinctly merge its cyber and electronic warfare missions. Among NATO member states, CEMA was only replicated doctrinally by the British Ministry of Defense in 2016.

[4] Colonel Patrick Justel « La guerre électronique : question du passé ou d’avenir ? » in Les cahiers de la Revue Défense Nationale, 2018 —

[5] « Guerre en Ukraine : “Orties”; l’ App disruptive au service du dieu de la guerre » by Adrien Fontanellaz — 21 mai 2022 —

[6] General Bonnemaison’s Hearing — Compte rendu N° 27 de la Commission de la défense nationale et des forces armées & « La cyberguerre dans les conflits du futur » 7 December 2022 — « Cyber : champ de lutte informatique et d’influence » by Cmdr Loïc Salmon (R) — 19 January 2023 —

[7] Keir Giles « Handbook of Russian information warfare », NATO Defense College, 2016 —

[8] « Lessons from Russia’s cyber war in Ukraine », The Economist, 30 November 2022 —

[9] General Bonnemaison’s Hearing, op. citIn its

[10] « The surprising ineffectiveness of Russia’s cyber-war » — In its podcast on science and technology. The Economist examine why the cyber campaign against Ukraine seems to have fallen flat, and ask whether Russia’s digital prowess has been overestimated — 6 December 2022 —

[11] Nicolas Mazzuchi « La Russie et le cyberespace, mythes et réalités d’une stratégie d’Etat » in Revue Défense Nationale N° 802, Summer 2017 —

[12] James A. Lewis, « Cyber war and Ukraine » Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), June 2022 —

[13] The Economist, op. cit

[14] Aspirant Pierre Vallée, in La Note du Centre d’Études Stratégiques Aérospatiales (CESA), 06/2022 —

[15] The Economist, op. cit

[16] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[17]https://ww.businessinsider.com/russian-ew-campaign-in-ukraine-undermined-by-electronic- fratricide-2022-11?r=US&IR=T

[18] Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), Preliminary lessons in conventional warfighting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine : (February-July 2022) by Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi, Dr Jack Watling, Oleksandr V Danylyuk and Nick Reynolds — 30 November 2022 —

[19] Roman Horbyk, « The war phone mobile communication on the frontline in Eastern Ukraine », in Digital War — 21 octobre 2022 —

[20] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[21] The Economist, op. cit

[22] Jon Bateman, « Russia’s wartime cyber operations in Ukraine : military impacts, influences, and implications », Carnegie Endowment for International Peace — December 2022 —

[23] « L’étonnant flegme des développeurs informatiques ukrainiens » in Les Échos — 8 March 2022 —

[24] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[25] « Guerre en Ukraine : les cyber-attaquants, l’autre armée de Vladimir Poutine », La Tribune, 27 December 2022 —

[26] General Bonnemaison’s Hearing, op. cit

[27] The Economist, op. cit

[28] Ukraine Now: « Digital Country »: Digitalization has become Ukraine’s flagship topic » — « Digitalization has become Ukraine’s flagship topic and the state priority during the last two years. Taking the lead internally, the Ministry of Digital Transformation has the ambition to make Ukraine a world champion in being digital, and we are already the first ones who can use digital IDs with absolutely no internal restrictions. Here is how Ukraine moves forward with the concept of building a digital state and becoming the world’s leading country in terms of providing services for citizens and businesses.»

[29] « La transformation numérique à l’appui de la reprise en Ukraine note de l’OCDE » July 1, 2022 – In the face of the Russian offensive, the Ukrainian government’s digital response is built around three main pillars: « Digital infrastructure, internet restoration and development »; « Public services and registries »; and « Digital economy. » The planned actions are in the short term (from now until the end of 2022), the medium term (2023-25) and the long term (2026-32). (See pdf document)

[30] « The unique Ukrainian situational awareness system Delta was presented at the annual NATO event »: Oleg Danylov — 28 October 2022 —

[31] « La résistance ukrainienne passe aussi par le numérique » by Célia Seramour — 11 May 2022 — See also: « Y a ennemi » : quand un chatbot aide les forces armées ukrainiennes » by Marianna Perebenesiuk and Jérôme Poirot in DeskRussia: « On February 6, 2020, the Ukrainian Ministry of Digital Transformation launched a digital portal called « State and Me », better known by its acronym, « Diia », which also means « action » in Ukrainian. Designed as a system, Diia consists mainly of a web portal, an application for smartphones and a host of programs that are united by the same approach and whose functionalities complement each other. Many of the services offered have names that are as amusing as they are evocative: yaBaby, yaSupport, yaHousing, yaWork or even… yaEnemy! Thus, ieMaliatko (in English: ya Baby) aims to take into account all the formalities related to a birth. iePidtrymka (yaSupport) allows the delivery of a virtual card to benefit from various services. As for ieVorog (yaEnemy), unbelievable but true, it is the name of the chatbot proposed to Ukrainians to signal the presence of Russian soldiers or equipment. And the least we can say is that it is a hit – in the French and even Ukrainian sense of this expression. Arms depots and army headquarters, tanks, cannons, Russian troops and political collaborators: in the occupied territories, everything explodes, burns and smokes with singular precision and regularity. If these military successes owe part of their success to the information provided by the Ukrainian or Western intelligence apparatus, they also owe it to the information gathered by the population itself » — 1 December 2022 —

[32] « Armes de guerre numériques : applications et logiciels qui aident l’Ukraine à vaincre » by Kateryna Kistol — 13 December 2022 —

[33] « US-led Security Assistance to Ukraine is Working » in RUSI par Jahara Matisek, Will Reno and Sam Rosenberg — February 2023 —

[34] « La France entre surprises et lacunes sur le « combattant numérique » in FOB (Forces Operations Blog) — 25 January 2023 —

[35] Roman Horbyk, op.cit

[36] Roman Horbyk, op.cit

[37] « Ukraine is scanning faces of dead Russians, then contacting the mothers » in Washington Post — 15 April 2022 —

[38] « La France entre surprises et lacunes sur le « combattant numérique » par Nathan Gain in FOB (Forces Opérations Blog) — 25 janvier 2023 —

[39] Royal United Services Institute, op. cit

[40] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[41] Colonel Aymeric Bonnemaison, colonel Stéphane Dossé « Attention : Cyber ! vers le combat cyber électronique » — p189, Economica, 2014 —

[42] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[43] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[44] Jon Bateman, op. cit

[45] Colonel Aymeric Bonnemaison, colonel Stéphane Dossé, op. cit

[46] The Economist, op. cit

[47] James A. Lewis, op. cit

[*] Major General Jean-Marc Wasielewski (FR-Army retd) comes from the signal corps. After commanding the 54th Signal Regiment, then the Signal and Command Support Brigade, he served as a liaison officer at the US Army Signal School at Fort Gordon (Georgia) and as Defense Attaché to the French Embassy in Berlin.

Voir également (Version française) : « L’emploi de la Cyber-électronique en Ukraine » — 14 février 2023 —