Ukrainian journalists, fact-checkers and civil society play a crucial role in analysing and debunking Russian disinformation and war propaganda. This analysis written by Inna Polianska is reproduced with the courtesy of the UCMC (Ukraine Crisis Media Center).

Sources: EUvsDiSiNFO & Ukraine Crisis Media Center — September 02, 2022 —

by Inna Polianska [1]

Russia’s tradition of dehumanising and inciting hatred toward Ukrainians started long before the country’s 2014 military aggression against Ukraine. In fact, Russia’s imperial past and its more recent foreign policy have never accepted a sovereign Ukraine’s existence.

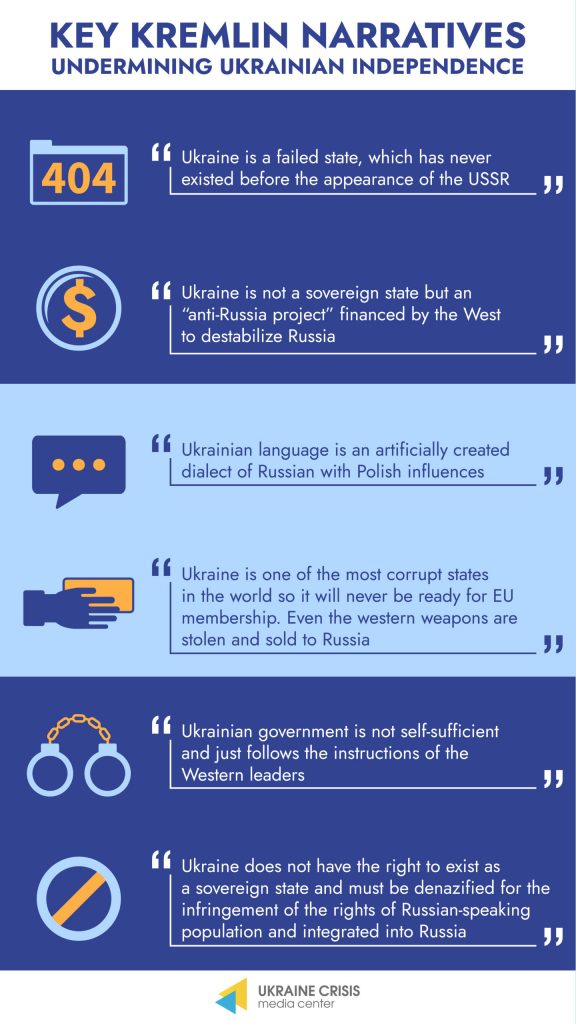

Since Ukraine gained its independence in 1991, the Russian propaganda machine has systematically devalued it, mocked it, marginalised it, and imposed historical myths upon it. Here are six key Kremlin narratives undermining Ukrainian independence and attempting to justify the military invasion of Ukraine.

Narrative #1: ‘Ukraine is a failed state which never existed before the USSR’s creation.’

One example of this narrative is the article, ‘What Russia should do with Ukraine’, by Timofey Sergeytsev, published by the Russian state-owned news agency RIA-Novosti. The text tries to prove that Ukraine has no right to exist as a sovereign state and must therefore be integrated into Russia. The same narrative appears in Vladimir Putin’s article, ‘On the historic unity of Russians and Ukrainians’, where Ukraine and Russia are portrayed as ‘one nation, a single whole’ and Vladimir Lenin is portrayed as a ‘founder of Ukraine’.

By calling itself ‘the USSR’s successor’ and emphasising the messianic role of the Soviet Union which ‘gave Ukrainians their statehood’, Russia avoids taking responsibility for the Soviet regime’s crimes against Ukraine. Such crimes included the Holodomor (1932-1933), the deportation of the Crimean Tatars (1944), and the repressions against Ukrainian intelligentsia, which led to the phenomenon of the “executed renaissance.’

Narrative #2: ‘Ukraine is not a sovereign state but an “anti-Russia project” financed by the West to destabilise Russia.’

Here is an example of how Russian propaganda delivers this narrative: ‘By 2014, Ukraine had evolved to the “Ukraine is an anti-Russia” stage. That is, everything that is happening now in Ukraine should be applied to Russia with the prefix “anti”. That is, exactly the opposite. And what is happening in Ukraine could happen in Russia as well, if we followed the same path as them.’ (Komsomolskaya Pravda, 2021.09.11)

This claim implies that Russia views the democratic processes in Ukraine as a direct threat to its own autocratic regime: ‘Ukraine is a warning for Russia, a danger. First of all, the danger that we have inside the country, and then, to some extent, the external threat, not so much for Russia as for Russians’.

Narrative #3: ‘The Ukrainian language is an artificially created dialect of Russian with Polish influences.’

The supposed ‘inferiority of the Ukrainian language’ is a classic claim found both in the works of the 18th-century Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov (who theorised that, due to Poland’s domination of western Ukraine, the ‘Little Russian dialect’ mixed with the Polish language and ‘got spoiled’) and in Russian imperial decrees prohibiting the Ukrainian language.

According to Ukrainian linguist Kostiantyn Tyshchenko, Ukraine shares 84% of its common vocabulary with the Belarusian language, 70% with Polish, 68% with Slovak, and only 62% with Russian. So Ukraine has more in common with Western Slavic languages than with Russian, which belongs to the Eastern Slavic languages group.

The politics of linguicide started in the Russian Empire. They were transformed into the politics of marginalisation in the Soviet Union where Ukrainian was commonly portrayed as the language of illiterate peasants. Soviet propaganda also accented the ‘rustic’ and ‘naïve’ nature of Ukrainian while describing Russian as a language of ruling elites and intellectuals. As a result, Russian propagandists called the Ukrainian language ‘fake’ and ‘artificial’ and blamed the Ukrainian government for ‘forcible Ukrainisation.’

At the Kremlin’s instigation, pro-Russian politicians in Ukraine have for years defended the manipulative claim that Ukraine is a ‘bilingual country’, the language issue being ‘off the agenda’ which ‘distracts from real economic and political problems.’

Inna Polianska – UCMC Photo

However, this did not prevent the Kremlin from using the Russian language and the so-called ‘oppression of the Russian-speaking population’ as a formal excuse for the war against Ukraine.

Narrative #4: ‘Ukraine is one of the most corrupt states in the world so it will never be ready for EU membership. Even Western weapons are stolen and sold to Russia.’

Despite the fact that, according to Transparency International data, as of 2021, Russia’s place on the corruption perception index (29) is worse than Ukraine’s (32), Russian propaganda pushes the narrative that Ukraine is ‘too poor and corrupt’ to join the EU. This ‘corrupt Ukraine’ narrative is tightly connected to our fifth narrative…Narrative #5: ‘The Ukrainian government is not self-sufficient and is just following the instructions of Western leaders.’

Here, the demonic West is controlling Ukraine like a ‘puppet’ and using it as a staging ground to weaken and defeat Russia.

This narrative is a logical continuation of Ukraine’s ‘external governance narrative’. Putin’s article illustrated this idea, portraying the Ukrainian state as a ‘fiction’ without ‘any historical basis’ which was created ‘for political purposes, as an instrument of rivalry between European states’. This is a classic example of how the Kremlin has tried to shape the international community’s perception of Ukraine as an object and not as a subjective and sovereign actor in international relations which therefore has to be ‘liberated’ and returned to Russian control. And finally…

Narrative #6: ‘Ukraine must be de-Nazified for infringing the rights of the Russian-speaking population and then integrated into Russia’.

According to the RIA news agency article, ‘What Russia should do with Ukraine’, Russia ‘does not need a Nazi, Banderite Ukraine, the enemy of Russia and a tool for the West to destroy Russia’.

Instead, the text proposes to ‘de-Nazify’ Ukraine and deprive it of sovereignty: ‘The de-Nazifier state, Russia, cannot take a liberal approach towards de-Nazification. The de-Nazifier ideology cannot be challenged by the guilty party that is being de-Nazified.’ The implication is that every Ukrainian government will be seen by Russia as ‘Nazi’ and the only acceptable path for Ukraine is the liquidation of its independence.

All these narratives have been used systematically since 2014. They are still used to incite hatred toward Ukraine and Ukrainians in Russian society, increasing domestic tolerance for the war and for violence. The effect is to create an alternative reality where Russia is defending itself from Western aggression and not committing genocide against the Ukrainian people.

To justify its invasion, the Kremlin tried to substitute a real Ukraine with a simulacrum made of cartoonish images, national stereotypes, and fakes. Many Russians believe it and accept the idea that the war with Ukraine was ‘unavoidable.’

As a result, Russian mainstream discourse condemns Ukraine for ‘provoking Russia’ and views the Russian war against Ukraine as a ‘correction of history’, a claim echoed by the brutal and autocratic Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad, one of Putin’s most ardent allies.

[1] Inna Polianska is an analyst in the Hybrid Warfare Analytical Group (Ukrainian Crisis Media Center) exploring Russian propaganda as part of its information war against Ukraine. A philologist by education, she is also currently working on a linguistic project, focused on exploring Ukrainian dialects.