Berlin before the Wall was a city wide open for espionage. It was the Golden Age of Intelligence, when American and British officers dueled with their Soviet counterparts across a divided Europe and beyond.

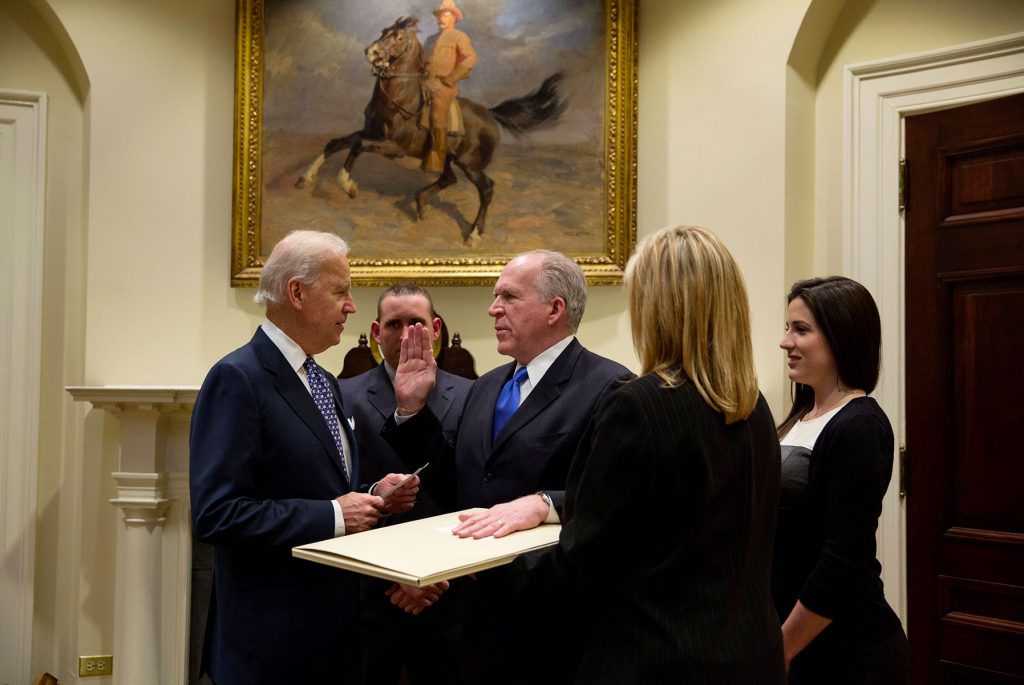

Opening remarks for CIA Director John O. Brennan as Prepared for Delivery at the OSS Society Donovan Award Dinner in Honor of Amb. Hugh Montgomery. Washington DC, November 7, 2015. Source : CIA.

Good evening everyone. Thank you, General Hugo, for your kind words. And I speak for everyone here in expressing our gratitude not only for your distinguished service to our country, but for your dedicated work on behalf of the women and men of the Office of Strategic Services.

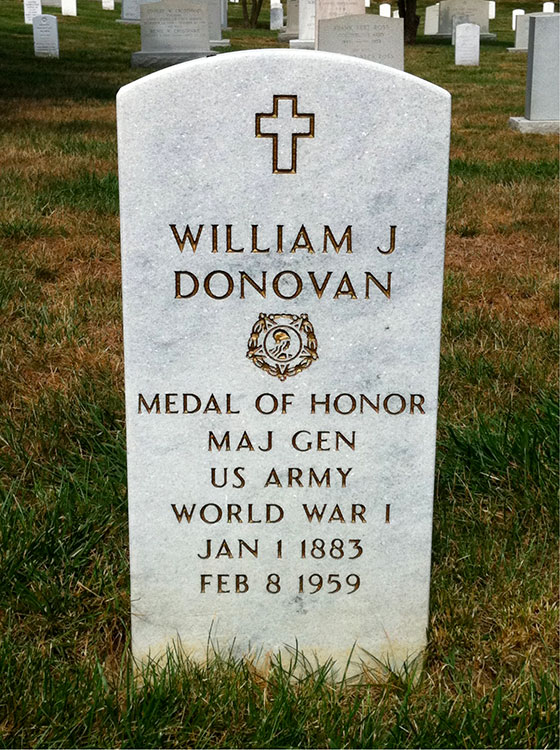

I also want to thank Charles Pinck and everyone at the Society for helping to keep alive the bold, intrepid spirit of the OSS. You do that by honoring and preserving the history of that legendary organization, and by paying tribute to extraordinary individuals with an award that carries the name of a great American hero, General William Donovan.

For all of us in the US Special Operations and Intelligence communities, General Donovan will forever be our lodestar. His courage, creativity, compassion, and resolve set the high standards for which we shall always strive.

Seventy years after his “glorious amateurs” helped win the greatest war ever fought, our Nation’s current generation of silent warriors carry on the OSS ethos of consummate skill, remarkable bravery, and quiet humility. Like their predecessors, they are handed assignments that entail great risk and difficulty, and they follow through with the same ingenuity, audacity, and commitment.

I wish I could recount here in detail some of the tremendous things I have seen our officers accomplish, often under very difficult circumstances. Just as the OSS did in its day, CIA takes pride in being given the hard tasks that others lack the capability, agility, or authority to carry out.

This is the third year that I have had the great honor to deliver remarks at this most auspicious event, and each year I am humbled as well as energized by being in the presence of such remarkable American patriots and heroes. Similarly, I am also humbled and energized by being in the daily presence of the remarkable modern-day patriots and heroes with whom I have the great honor to work and to lead at the CIA. Therefore, everyone here should rest assured and be confident that the OSS legacy that is so palpably felt by all of us tonight is being proudly upheld today by the women and men of CIA.

And until last year, the CIA workforce still counted among its ranks a leader who had served under General Donovan—and 20 CIA Directors. He is a pioneering intelligence officer and a great American; one of the finest, most talented individuals who ever joined the Clandestine Service; and a dear friend and colleague to all of us fortunate enough to know him: Ambassador Hugh Montgomery.

Last year I had the high privilege of presenting Ambassador Montgomery with the Distinguished Career Intelligence Medal. I am quite sure that no recipient of that decoration has ever had a more storied or accomplished career.

Tonight, on behalf of CIA officers past and present, it is my honor and pleasure to present Ambassador Montgomery with the William J. Donovan Award. And there is no doubt that his old boss the General would strongly approve.

As we saw in that excellent video, Ambassador Montgomery made vital, enduring contributions to our Nation’s security and to the fight against fascism and communism over the course of many decades.

To achieve a record as impressive as Hugh’s requires courage, intellect, sophistication, creativity, and dedication, among many other qualities. But the greatest officers also have a strong grounding in the fundamental skills of our profession, and Hugh is no exception—especially, as we all know, when it comes to fluency in languages.

As noted in the video, he followed in his mother’s linguistic footsteps, and used his command of German and other languages to get him into the OSS, where he used it to great advantage in Germany and Austria by claiming to be the son of German parents who had emigrated to South America—a cover story supported by his fluent Spanish.

Once, when Hugh was hunting down war criminals, he was given the name and address of a German baron who was a senior Nazi official in Munich. A butler answered the door to find a couple of grungy GIs, and told them the baron was not receiving visitors.

“I hate to interfere with the baron’s schedule,” Hugh replied in perfect German, “but the baron will receive us now.” Moments later, the baron was in the back of Hugh’s Jeep, on his way to being locked up.

Responding to the entreaties of his OSS boss, Richard Helms, to join him at the CIA—the “Pickle Factory,” as Hugh’s generation called it—Hugh would spend 24 of his 28-years as an Agency staff officer overseas, serving as Deputy Chief of Station in Moscow, Rome, and Paris, and as Chief of Station in Vienna and Rome.

Hugh’s first six years as a CIA officer were in Berlin before the Wall went up—a city wide open for espionage and the perfect proving ground for a young case officer. It was the Golden Age of Intelligence, when American and British officers dueled with their Soviet counterparts across a divided Europe and beyond.

Along with legendary Base Chief Bill Harvey and maverick case officer Walter O’Brien, Hugh helped run the remarkable Berlin Tunnel operation for nearly a year before the Soviets shut it down in April 1956.

Hugh’s tremendous success in Berlin led to his appointment as Deputy Chief of Station in Moscow. And it was there, at the height of the Cold War, that Hugh was involved in handling the agent who many believe was the most valuable Russian asset ever run by our Agency—GRU Colonel Oleg Penkovsky.

Hugh quickly mastered “Moscow rules,” the elaborate tradecraft methods required in such a hostile operational environment. Personal contact with assets was virtually impossible. Dead drops were essential.

In one case, a drop was arranged to be made at Spaso House, the US Ambassador’s residence in Moscow, during a Fourth of July party. Penkovsky would leave a package in the flush tank of a toilet at the residence.

But when Hugh went in to pick up the package, he found that it had sunk to the bottom of the tank—an ancient fixture mounted on the wall high above the toilet. Using his best case-officer skills, Hugh hoisted himself onto the sink so that he could reach into the tank and recover the package. But, alas, Hugh’s weight—appropriate for his height but nevertheless formidable owing to his muscular frame and abundant intellect—tore the sink from the wall.

With one arm dripping wet, Hugh managed to slip out of the bathroom with the treasured secrets safely secured on his person without attracting attention. But at the next Embassy staff meeting, the Ambassador said he wanted to know the name of the Russian S.O.B. who trashed his wife’s powder room.

And we still haven’t paid the State Department for the broken sink.

Hugh’s mastery of clandestine tradecraft is certainly one of the elements that make him such an extraordinary officer, but it is only part of the story. Human intelligence is very much a social endeavor. Personality, character, charm, and charisma help forge lasting relationships. Hugh and Annemarie made many, many close friends over the years, including heads of state and other important figures whose personal ties could be of service to our country.

Of course, not everyone Hugh encountered on the job became a close friend. While serving in Rome, he received a phone call from Philip Agee, the notorious Agency turncoat who exposed the identities of hundreds of our officers. Agee demanded to meet with Hugh and threatened to “destroy” him if he refused.

Hugh’s response to Agee was direct, succinct, and quite fitting for someone with the capabilities of an OSS commando. “If I could get my hands on you,” he said, “I would gladly wring your neck, so I guess that makes us even.”

Hugh will always belong to CIA, even though we have not always been able to keep him to ourselves. In 1981—after serving as National Intelligence Officer for Western Europe and receiving the Distinguished Intelligence Medal from Director Bill Casey—President Regan appointed him to direct State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

Four years later, Hugh was given the rank of Ambassador—a rare honor for an Agency officer—and was asked by his friend and former Deputy Director of CIA, General Vernon Walters, to serve as his deputy at the United Nations.

Turtle Bay Neighborhood on the East Side of Midtown Manhattan was not exactly postwar Berlin, but Hugh was uniquely qualified to excel in a venue that had representatives from all the world’s nations crammed into five square blocks of New York City. Hugh vastly improved intelligence support to the US Mission, establishing the close relationship that endures to this day.

As Hugh’s UN tour was coming to an end in 1989, so too was the Cold War. In December 1991—the very month the Soviet Union ceased to exist—CIA Director Bob Gates appointed Ambassador Montgomery to be his Special Assistant for Foreign Intelligence Relationships.

An important legacy of Hugh’s pioneering work was to set precedents for the sharing of US intelligence with UN agencies, especially war crimes tribunals. Having brought Nazis to justice some fifty years earlier, Hugh ensured that the international community had the information needed to indict those who committed atrocities during the violent breakup of Yugoslavia. His efforts also laid the groundwork for the massive expansion of information sharing and joint operations with our foreign partners in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

By virtue of the major role he played in the story of our Agency, Hugh possesses a rare insight into its past, which former CIA Director Hayden recognized when he selected Hugh to be the Director of the DCIA History Project in 2007. In that capacity, Hugh made vital contributions to the historical record, drawing from his many years of experience.

Hugh Montgomery has come a long way since landing in the fields of Normandy. In clandestine service to our Nation, he faced risk and ambiguity with valor and purpose, always embodying the good faith, integrity, and decency of this great country. We are exceptionally fortunate to be heirs to the history that he made.

And every step of the way throughout his distinguished career, Hugh relied on the love and support of his wonderful family. As Judge Webster said, Annemarie is most certainly shining down on us tonight, and is looking upon her most precious Hugh with tremendous love, pride, and admiration.

And now, it is one of the greatest honors of my professional career to invite one of the legendary icons of the intelligence profession and one of the greatest American heroes of our time, Ambassador Hugh Montgomery to join me on stage for the presentation of the Donovan Award.

Related Topic :

« The Challenges of Ungoverned Spaces » by John O. Brennan (13-07-2016).

« The Overarching Challenge of Instability » by John O. Brennan (29-06-2016).

« ISIL IS a Formidable, Resilient, and Largely Cohesive Enemy » by John O. Brennan (16-06-2016).

« CIA : Between Transparency and Secrecy » » by David S. Cohen (21-04-2016).

« Instability Has Become a Hallmark of Our Time » by John O. Brennan (03-03-2016).

« Good Intelligence Is the Cornerstone of National Security Policy » by John O. Brennan (16-11-2015).

« CIA & The OSS Legacy » by John O. Brennan (07-11-2015).

« Addressing Challenging and Consequential Issues of Our Time » by John O. Brennan (05-11-2015).

« Intelligence : Between Policy Success and Intelligence Failure » by John O. Brennan (15-10-2015).

« The CIA of the Future » by David S. Cohen (15-09-2015).

« Democracy Does Not Keep Secrets Merely for Secrecy’s Sake » by John O. Brennan (15-09-2015). »U.S Intelligence in a Transforming World »by John O. Brennan (13-03-2015).