Major Creed Napier is a US Air Force officer and Combat Search and Rescue (CSAR) pilot who spent over three years in France with the 1/67 Escadron d’hélicoptères “Pyrénées.” He has deployed with the US in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and with the French in Support of Operation Barkhane.

As an American officer, I never expected to be a pilot on the first operational jump in the history of a French commando unit.[1] Nonetheless, I found myself in the dark skies of Sub-Saharan Africa on a warm winter night in 2016, as the copilot of a French HM-225 Caracal. Once in the air, the aircraft reached its physical altitude limit after a long, laborious climb. I was on the controls in the right seat and started a timer to make sure we limited the effects of hypoxia.

French HM-225 Caracal flying over the desert

On my left, the aircraft commander, a lieutenant, was orchestrating this historic jump. How exactly did a foreigner and a French lieutenant end up flying this important flight for the opening mission of an anti-terrorist campaign in Africa ?

System D

The answer has to do with the way of doing business in the French Air Force (FAF). System D is the somewhat vulgar name the French use to describe one aspect of their culture – the fact that everyone must fix their own situation in order to get their job done. It is especially characteristic of the helicopter community. The “D” stands for “démerde”. By way of example, System D goes into effect when an officer is sent to a base in Belgium for a conference, but is not allocated a rental car to get him from the hotel to the base.

French HM-225 Caracal landing flying over the desert

System D also goes into effect when a helicopter makes an emergency landing in the middle of the African desert and needs an engine swap in place. These both occurred in my unit, and in both cases, the people involved solved their own problems.

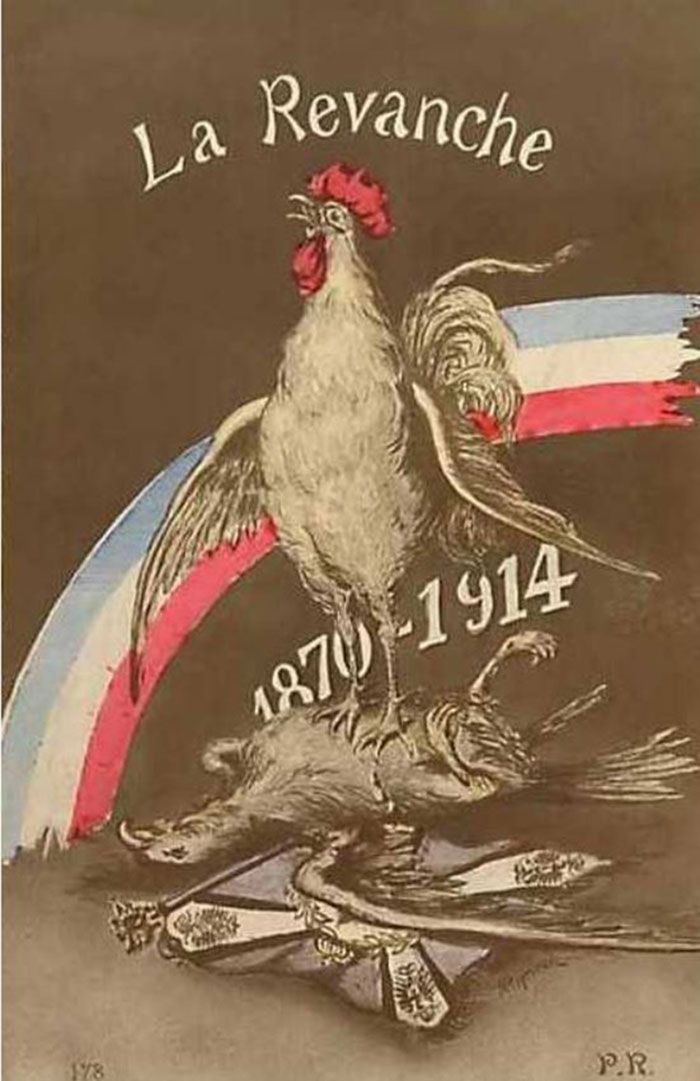

Gallic rooster ready to fight…

There seem to be two factors that create System D : means and culture. First, as compared with the United States, France has far fewer squadrons, aircraft, and money. The FAF is much smaller than the US Air Force (USAF) by orders of magnitude. French helicopters did not have satellite radios, and with only two aircraft deployed, there was often no two-ship formation because one was down for maintenance. Nevertheless, the FAF is engaged in operations around the world, fighting the same enemies as the US in the same places. There is a joke that perfectly captures this: “France has the ambitions of the United States with the budget of Portugal !”

The second contributing factor is culture. System D reflects a larger national culture where the first response to a request is often “no.” This is off-putting to those coming from outside cultures, but this initial “no” really functions as a filter. It really means, “tell me why this is important.”

Caracal flying over African desert

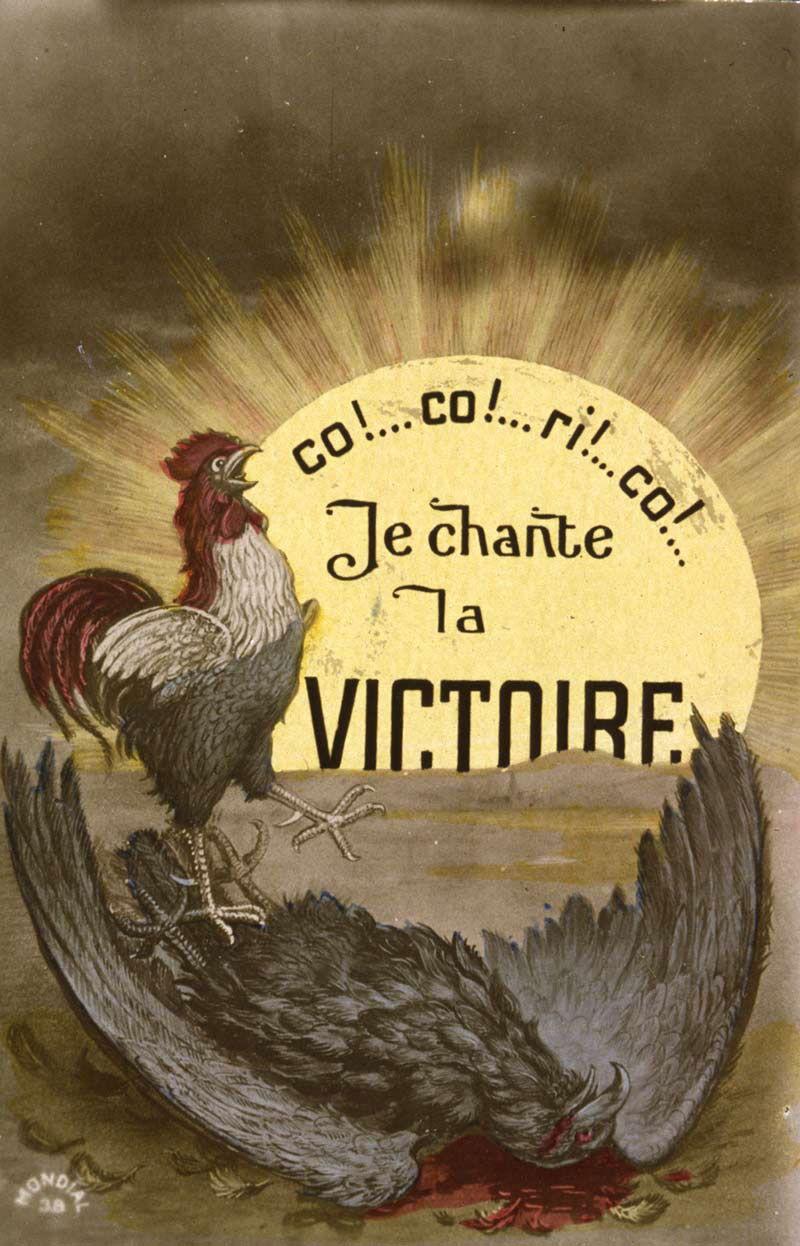

In the FAF, the “why” always matters and when you have a compelling reason, nearly anything can be accomplished. It just requires selling an idea and getting past limited of resources. Incredibly, the French do this on a daily basis ! A joke by the late comedian Coluche perfectly illustrates this. He quipped that the rooster is the French emblem “because it is the only bird that manages to sing with both feet in the ‘merde’.”

1914 : The battle between Gallic rooster vs. German eagle… By Ch. Renaud

It is easy to see the problems with System D. It means that people are often not supported or that they have to solve problems on their own. It means that the scale of operations and exercises might be limited because so much is “do it yourself.” It requires individuals who are strong-willed and can persist in getting important things done despite resistance. It is not for the faint of heart. Despite these obvious drawbacks, there is a positive side to System D if one looks deeper.

Vitamin D?

Perhaps System D is actually Vitamin D as there are several important benefits. First, it creates more responsible and rresilient individuals at lower levels, which ensures centralized control / decentralized execution. Second, it creates organizational agility and adaptability. Finally, although nothing is easy, almost anything is possible.

System D creates more responsible individuals because they learn early that if they are to be successful, they must take matters into their own hands. People who thrive in this way become trusted and creatively problem solve, since they cannot always rely on a big support system. They learn how other units function and develop relationships in order to accomplish the mission. Taken together, the characteristics of responsibility, trust, relationship building, and autonomous problem solving, help ensure a most hallowed command and control principle – centralized control and decentralized execution.

Caracal flying over the Pyrenees mountains

Next, System D allows units to adapt. This occurs because individuals are already accustomed to overcoming difficulties. The gap between overcoming difficulties to change something and for normal operations is small. So only a small difference in effort is required for adaptation. Moreover, if the reason for the change is compelling, it is normally accepted. French officers do not hesitate to do something that is non-standard because it will take into account current conditions. I was endlessly impressed with their ability to know the regulations and standards, but to deviate frequently, without putting flight safety at risk. These constant deviations would be disruptive in other cultures, but for the French, that is the standard. When smaller size is coupled with this culture, agility results. This creates organizational dynamism, which is the basic motor of the FAF.

Finally, although nothing is easy, anything is possible. It follows from the last line of logic that if one must overcome resistance, then that can go in any direction, which opens up the aperture of possibilities. While in France I planned the longest recorded Caracal flight, supported the initial operational capability of night Helicopter Air-to-Air Refueling, developed new tactics, and supported the procurement of a new weapon. In the USAF, most of this would be work for the weapons school or the test unit, but in the FAF, it is on the front line. Innovation is not just the purview of specified units, it occurs everywhere.

A NATO Hercules 130P refuels two FAF Special Operations Command HM-225 Caracal

My French helicopter pilots colleagues reading this may not feel the same awe that I do, because they probably feel that the results of their hard work feels small in comparison to the effort put in. My response ? That is exactly the source of strength and resilience of the FAF.

Conclusion

Napoleon did not care much for the rooster as a symbol of France because it had no strength, preferring instead the eagle. The rooster became a Gallic symbol during Christendom as a reminder of the Passion of Christ (the rooster crowed when Judas betrayed Jesus) and the rooster’s crow came to symbolize renewed victory at the start of each day. On that dark night in Africa as I pondered how a lieutenant and a foreigner could be flying such a symbolic flight, I realized that it was the rooster at work. In the US, we would have sent the bald eagle – our most experienced pilot or possibly the commander. American leaders want to show their combat mettle and willingness to do what they are asking their subordinates to do. In the FAF, however, sending the most experienced pilots might undermine the existing trust. The lieutenant was a product of System D, and our mission was executed flawlessly. Contrary to Napoleon, it turns out that the rooster has a strength of its own – resiliency.

Napoleon did not care much for the rooster as a symbol of France because it had no strength, preferring instead the eagle. The rooster became a Gallic symbol during Christendom as a reminder of the Passion of Christ (the rooster crowed when Judas betrayed Jesus) and the rooster’s crow came to symbolize renewed victory at the start of each day. On that dark night in Africa as I pondered how a lieutenant and a foreigner could be flying such a symbolic flight, I realized that it was the rooster at work. In the US, we would have sent the bald eagle – our most experienced pilot or possibly the commander. American leaders want to show their combat mettle and willingness to do what they are asking their subordinates to do. In the FAF, however, sending the most experienced pilots might undermine the existing trust. The lieutenant was a product of System D, and our mission was executed flawlessly. Contrary to Napoleon, it turns out that the rooster has a strength of its own – resiliency.

With military spending set to increase over the next eight years in France, the challenge will be to retain this resiliency, adaptability, and effectiveness, while the temptation will be to make things easier. Hopefully this helps illuminate some of the less obvious trade-offs.

Major Creed Napier and his wife before returning home – All rights reserved ©

Finally, to France’s allies. You may be uncomfortable because your French colleague does not think like you, speak like you, somehow has fresh croissants in combat, eats “foie gras”, drinks Ricard, and is concerned about tonight’s “apéro”. You may also think that things are not planned out in enough detail or the way you prefer, but I implore you to trust them. Remember that they are professionals at getting out of the shit to achieve the job.

[1] Major Creed Napier is a US Air Force officer and Combat Search and Rescue (CSAR) pilot who spent over three years in France with the 1/67 Escadron de Hélicoptères “Pyrénées.” He has deployed with the US in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and with the French in Support of Operation Barkhane.

Useful links :

L'EH "1/67" Pyrénées de nouveau à l'honneur : GDA Philippe Carpentier (2s) ─ Bordeaux, le 11 février 2014.

Charles Creed Napier honored P2 (Flying Cross recipient). Monterey, California, October 16, 2013.

L’escadron d'hélicoptères (EH) 01.67 « Pyrénées » de l'armée de l'Air : Entretien avec le LCL Fabien Gisbert, commandant l'EH 1/67. Cazaux, le 21 juin 2013.

Hélicoptères : un savoir-faire français de haut niveau : Allocution du GBA Philippe Gasnot, commandant la Brigade d’Appui et de Projection du Commandement des forces aériennes (CFA) lors des 50 ans de l'Escadron d'hélicoptères 1/67 Pyrénées sur la BA 120 "Commandant Marzac" de Cazaux, le 4 juillet 2012.