We just created the Directorate of Digital Innovation to accelerate the integration of our digital and cyber capabilities across all CIA mission areas—espionage, all-source analysis, open-source intelligence, liaison engagement and covert action says John Brennan..

Remarks as Prepared for Delivery by Central Intelligence Agency Director John O. Brennan at the Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, 13 July 2016. Source : CIA.

Thank you, General Allen, and thank you all very much.

It is a pleasure to visit Brookings and to be among good friends and colleagues.

Bruce Riedel and I have known each other for over 35 years, so I very much look forward to our conversation and to addressing your questions.

First, though, I want to start off with some brief remarks. I have spoken recently in public settings about the many overseas threats that we face as a Nation, and the importance and challenges associated with dealing with countries like Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, and I will be happy to address your questions about such issues.

But for now, I would like to focus on how CIA is working to meet these challenges—specifically, the challenges of ungoverned spaces and of the digital revolution, two defining features of global instability that keep us quite busy at Langley.

* * * *

Clearly, the world in 2016 is witnessing a significant amount of instability, and has been for some time. Instability is a vague and antiseptic term, but we all know that it carries some very real costs—especially in terms of humanitarian suffering, rising extremist violence, and diminishing freedom throughout the community of nations.

For instance, Freedom House this year reported an acceleration in a decade-long slide in democracy around the world. The number of countries showing a decline in freedom for the year—72—was the largest since the downward trend began.

The challenges we face today are unprecedented in both their variety and complexity. They are highly fluid, constantly shifting and taking on new dimensions. And they are increasingly interconnected, testing our ability to anticipate how developments in one realm will shape events in another.

When CIA analysts consider the trends that are shaping the coming decade, they look at dynamics such as rapid population growth and urbanization in the developing world. They look at technological advances that vastly outpace the ability of governments to manage them, as well as at low economic growth globally.

If these trends hold, we could see greater volatility and increased demands on nation-states, which are already under the greatest stress we have seen in many years, perhaps going back to the period after the First World War. Governments worldwide have found that handling the daunting array of 21st century challenges on their own—those related to economics, security, technology, demographics, climate change, and so on—is increasingly difficult, if not impossible.

The United States and other nations are lending assistance to many of these countries so that they can better deal with these pressures and maintain cohesion. And just as the various departments of our government provide aid and expertise to their counterparts in weakened states, the Agency plays a role as well. In many cases, CIA helps to enhance the capability of foreign security and intelligence services so they can increase the quality and quantity of intelligence they provide us to help address threats of mutual interest, such as violent extremism, within and from across their borders. But our assistance and partnership come with conditions–these intelligence and security services must adhere to standards of professional conduct and respect for human rights.

And nowhere do we find greater challenges to effective governance than in the region that stretches from the Maghreb to South Asia. Faced with rapidly growing and youthful populations, North Africa and the Middle East have some of the world’s highest unemployment among 12 to 24-year-olds. These trends foster the appeal of militant ideas in states that are already struggling to govern territory and meet the basic needs of their people.

Not surprisingly, this is the region where we have seen a dangerous rise in ungoverned spaces—the kind of places where the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant was able to establish its reign of terror.

And these are precisely the kind of places in which CIA must operate.

To provide the President and his senior advisers with the insights they need, the Agency collects critical intelligence wherever there is a need. And when we must acquire ground truth in austere and difficult locations—where there is no US Government presence or established liaison partner—the conventional approach of operating out of a Station is not an option.

Given this imperative, one of the things we are looking at is how we enhance our expeditionary capabilities, which depend on the ability to operate with agility and a light footprint. And because many of our greatest national security challenges have emerged from ungoverned spaces—and are likely to do so in coming years—CIA must be expeditionary in both spirit and action.

This is a tradition that stretches back to the Second World War, when the Agency’s predecessors in the Office of Strategic Services parachuted behind enemy lines in occupied Europe. And only 15 days after the September 11th attacks, teams of CIA officers were the first Americans on Afghan soil, leading our Nation’s response by taking the fight to al-Qa‘ida.

And whether in expeditionary missions or our day-to-day operations, we have seen since 9/11 that the power of integration is the single most decisive factor in optimizing our intelligence capabilities across the board. To that end, the Agency last year launched a Modernization program, a strategic effort to better integrate and leverage CIA’s unique as well as many strengths.

The centerpiece of our Modernization initiative was the creation of 10 Mission Centers, the line organizations that now bring together our operational, analytic, technical, digital, and support disciplines. Six of these centers focus on regions, such as Africa and the Near East. And four focus on functional areas, such as Counterterrorism and Counterproliferation.

We needed to create an architecture that would best position the Agency to respond quickly and effectively to current and future challenges. Today, our analysts, our case officers, and our technical, digital, and support officers work together within these Centers—in much the same way they have learned to collaborate in the field. And that means we can come up to speed far more quickly on any breaking issue that might emerge somewhere on the globe.

* * * *

Beyond the challenge of ungoverned spaces, the digital revolution is perhaps the defining feature of our unstable world, in both the most positive and negative ways.

The cyber realm and information technology have fundamentally transformed the most prevalent means of human interaction. These technologies have given rise to new information-based industries that have displaced older ones, sometimes deepening gaps within societies and between the developed and underdeveloped worlds. They enable social interaction that can be swift and destabilizing, as we saw with the so-called Arab Spring. And they invest individuals with unprecedented influence and even power—for better or worse.

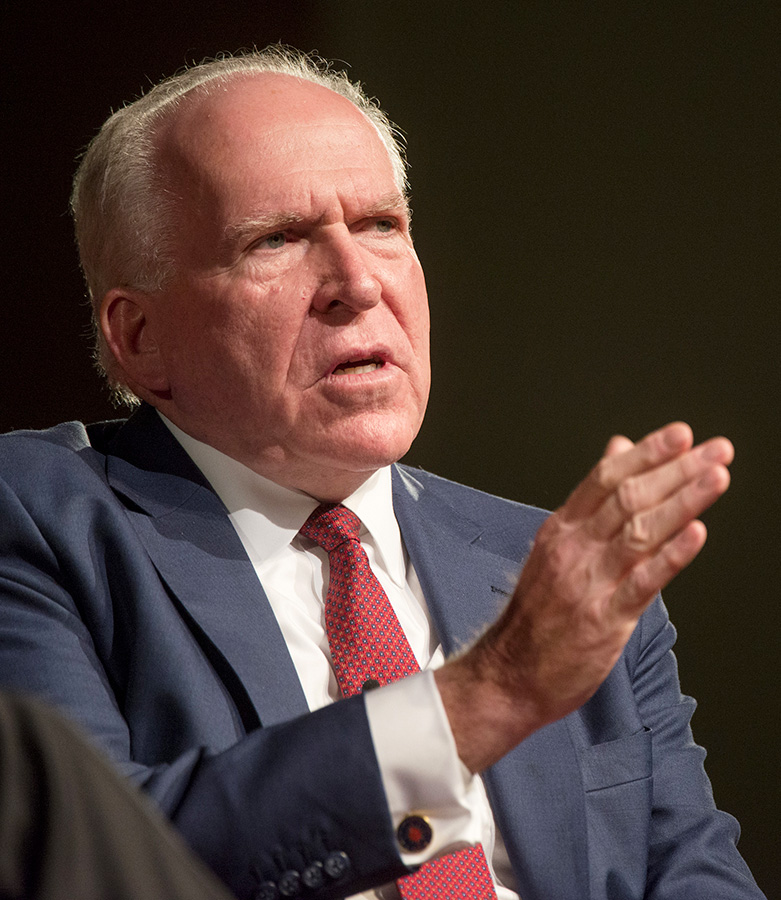

John O. Brennan – Photo Jay Godwin

We needed to create an architecture that would best position the Agency to respond quickly and effectively to current and future challenges. Today, our analysts, our case officers, and our technical, digital, and support officers work together within these Centers—in much the same way they have learned to collaborate in the field. And that means we can come up to speed far more quickly on any breaking issue that might emerge somewhere on the globe.

* * * *

Beyond the challenge of ungoverned spaces, the digital revolution is perhaps the defining feature of our unstable world, in both the most positive and negative ways.

The cyber realm and information technology have fundamentally transformed the most prevalent means of human interaction. These technologies have given rise to new information-based industries that have displaced older ones, sometimes deepening gaps within societies and between the developed and underdeveloped worlds. They enable social interaction that can be swift and destabilizing, as we saw with the so-called Arab Spring. And they invest individuals with unprecedented influence and even power—for better or worse.

Cyber makes it possible for our adversaries to sabotage vital infrastructure without ever landing an agent on our shores. And we have seen how our own citizens can be indoctrinated by terrorist groups online to commit terrible acts of violence here at home.

Moreover, these technologies are transforming how an intelligence service, which is a quintessential information-based enterprise, conducts business. And we at CIA fully understand that how we rise to the challenge of the digital age will determine the extent of our future success.

That’s why last year, as part of our Modernization program, we created a Directorate of Digital Innovation, the first new Agency Directorate in more than a half-century. This new Directorate is at the center of the Agency’s effort to hasten the adoption of digital solutions into every aspect of our work. It is accelerating the integration of our digital and cyber capabilities across all our mission areas—espionage, all-source analysis, open-source intelligence, liaison engagement and covert action.

The Directorate is deeply involved in our efforts to defend against foreign cyber attacks. It has an important role to play in human intelligence collection by helping safeguard the cover of our clandestine operatives in the Information Age. Equally important, the Directorate oversees our Open Source Enterprise, a unit dedicated to collecting, analyzing, and disseminating publicly available information of value to national security.

Multiple elements of the Agency in the past have responded to the challenges of the digital era. But if we are to excel in the wired world, the digital domain must be part of every aspect of our mission.

In practical terms, it means that our operations officers must be able to maintain their cover in a dynamic digital environment and collect in it as well. It means that our analysts must be able to quickly process and analyze enormous volumes of data. And it means that our IT experts must be able to harden our networks against intrusion and better protect our sources and methods.

We at CIA—and our colleagues throughout government—are doing what we can to meet the challenges of the digital revolution. But even “whole-of-government” solutions are simply not enough when it comes to cyber.

Some 85 percent of the internet is owned and operated by the private sector, which is why we need to have an honest, vigorous dialogue between public and private sector stakeholders about government’s proper role in the cyber domain.

In that vein, we need to have a more robust and comprehensive national discourse about how the government and the private sector must work together to safeguard the security, reliability, resilience, and prosperity of the digital domain. Such public-private dialogue and partnerships will be increasingly important as technologies advance and new fields of endeavor emerge as we move further into the 21st century.

* * * *

It is a tremendous honor every day for me to carry the title of Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. It is my privilege and pleasure to work with a team of patriots who put themselves on the front lines to keep their fellow Americans safe and secure. I could not be prouder of what they accomplish, day in and day out—not only for our country, but for our friends around the world.

Related Topic :