France’s Fatal Gifts – How Louis XIV and Voltaire Accidentally Build Prussia’s War Machine

Let’s explore a central irony of Franco-German history through two episodes that unfolded in Berlin.

The first act describes how the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685 caused a flight of Huguenot talent. Welcomed with open arms by a devastated Prussia, these French artisans, entrepreneurs, and military officers provided the human and technical capital necessary for its rise.

The second act analyzes how Frederick the Great, in the 18th century, imported the spirit of the French Enlightenment, notably through his relationship with Voltaire. He used this philosophy not to liberate his people, but to rationalize his administration and perfect his army.

Thus, through the exile of its blood and the export of its spirit, France paradoxically provided its future Prussian rival with the tools of its own power—a history lesson etched in the stones of Berlin.

Among the eminent figures of the French Huguenots in Berlin are Daniel Chodowiecki (a painter of Huguenot descent through his mother), Emil du Bois-Reymond (a physiologist of Huguenot origin and one of the founders of electrophysiology), Karl Ludwig Michelet (a philosopher of Huguenot descent), and Pierre Louis Ravené (an industrialist and art collector).

These figures contributed to the lasting influence of Berlin’s Huguenot community in various fields, reflecting the importance of their emigration following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685.

The Huguenot Paradox and the Mirror of the Enlightenment

Table of Contents

by Joël-François Dumont — Berlin, September 24, 2025 —

Introduction: Iron and Intellect – How France Unwittingly Armed Prussia

Berlin, in its very stones and collections, tells a Franco-German story more complex and ironic than it first appears. Far from the simple narratives of 20th-century wars, the German capital is the stage for two little-known chapters where France, at the height of its glory, unintentionally forged the power of its future rival.

This story of blood, intellect, and unforeseen consequences reveals a disquieting truth: a nation’s greatness and its misfortunes are often the fruit of its own contradictions. The account that follows is not one of aggression, but of transfer; not a story of conquest, but of an involuntary gift.

The first act of this historical drama is a transfer of “blood”: that of the Huguenots, driven from the kingdom of France by a quest for absolute religious unity.

In 1685, Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes caused a hemorrhage of talent, a flight of vitality that found refuge in an exhausted Brandenburg-Prussia. This exile was not a mere migration; it was a providential transfusion that brought the nascent Hohenzollern state the human, technical, and moral capital necessary for its reconstruction and ascent. France, in seeking to purify itself, offered its neighbor the builders of its future strength.

The second act is a transfer of “intellect”: that of the French Enlightenment, which fascinated the courts of Europe. In the 18th century, Frederick II of Prussia, the “Philosopher-King,” imported French genius to polish his court, shape his state, and sharpen his political intelligence.

His tumultuous relationship with Voltaire at Potsdam symbolizes this appropriation. But here again, the paradox is cruel. France exported a philosophy of reason, efficiency, and criticism that it struggled to apply to its own aging monarchy. Frederick II seized upon it not to liberate his people, but to rationalize his army, modernize his administration, and conduct an aggressive foreign policy. He adopted the methods of the Enlightenment while rejecting its moral purpose, transforming philosophy into a weapon in the service of raison d’État.

These two episodes, omnipresent for those who know how to see them in Berlin’s museums, from the Gendarmenmarkt to Charlottenburg Palace, demonstrate how France, through its own decisions, provided Germany with the tools of its own power. Berlin thus stands as a mirror of French history—a broken mirror reflecting a distorted and ironic image of its own genius.

Act I: The New Blood of Prussia – The Hemorrhage of French Talent (1685-1713)

Chapter 1: “One Faith, One Law, One King”: France at its Apex and on the Eve of a Monumental Error

The decision to revoke the Edict of Nantes in October 1685 was not a whim but the logical and relentless culmination of the absolutist conception of power embodied by Louis XIV.

For the Sun King, the monarchy was of divine right, and the king, as “God’s lieutenant on Earth,” was duty-bound to ensure the unity of his kingdom in all matters.[01] The formula “one faith, one law, one king” summarized this vision, where religious plurality—tolerated by his grandfather Henry IV as a necessary evil to end the Wars of Religion—appeared as an intolerable anomaly, a flaw in the perfect edifice of the state.[02]

This quest for ideological homogeneity took precedence over all other consi-derations, including the economic and social stability of an already fragile kingdom.

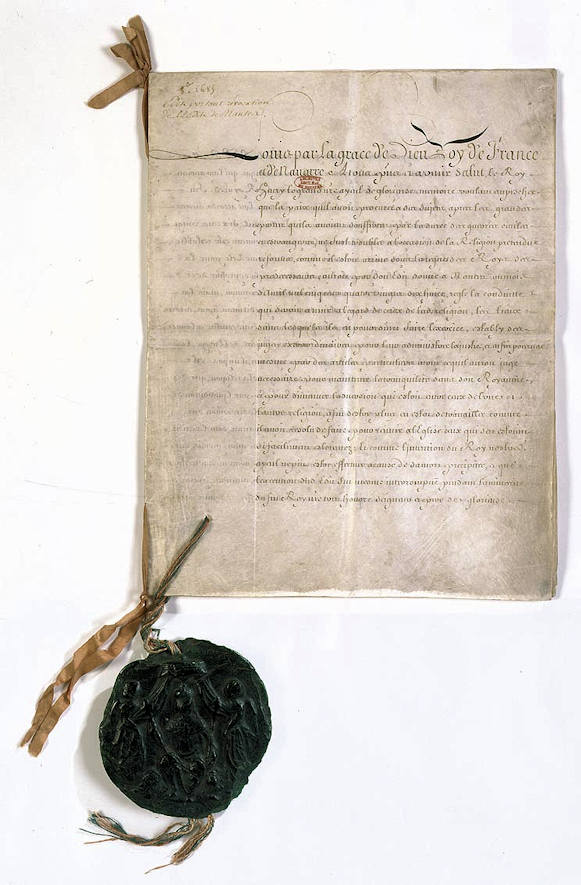

Edict of Louis XIV revoking the Edict of Nantes (page 1) Archives Nationales

From the beginning of his personal rule in 1661, Louis XIV initiated a policy of “slow strangulation” against the “Pretended Reformed Religion” (R.P.R.).[03]

The process was methodical. It began with a “strict” application of the Edict of Nantes, meaning a legal interpretation so restrictive that anything not explicitly permitted became forbidden.[04]

This was followed by a wave of repressive measures aimed at marginalizing Protes-tants: gradual exclusion from municipal and judicial offices, denial of access to many guilds and liberal professions (lawyers, doctors, printers), and the suppression of the bi-partisan courts.[05] At the same time, the state attacked the community’s structures: churches built without formal authorization were systematically demo-lished, national synods were banned, and theological academies were closed one after another.[05] To encourage conversions, a “Conversion Fund” (Caisse des conversions) was established, offering financial rewards to those who renounced their faith.[03]

« Dragonnade »: illustration by Maurice Leloir, Photo Gustave Toudouze (1931)

When these legal and financial pressures proved insufficient, the crown resorted to physical violence. Starting in 1681, the intendant of Poitou, Marillac, inaugurated the infamous “dragonnades.” This policy consisted of forcibly quartering soldiers—the dragoons, known for their brutality—in Protestant homes, with the implicit authorization to commit any excess to obtain conversions.[06] Ruined and terrorized, families renounced their faith in droves under duress.

This policy of religious eradication was carried out in a disastrous economic context. The reign of Louis XIV, particularly after 1685, was marked by incessant wars, a crushing tax burden, and devastating subsistence crises, such as those of 1693-1694 and 1709-1710, which led to famine and epidemics.[07] Yet the Huguenots, estimated at around 850,000 people, constituted a disproportionate share of the economy’s driving forces. As artisans, merchants, and entrepreneurs, they dominated key sectors and held a significant share of the kingdom’s business.[08] In persecuting them, the monarchy was not only violating consciences; it was sawing off the branch on which a significant part of its own prosperity rested.

The final act, the Edict of Fontainebleau signed on October 18, 1685, was presented not as an act of persecution, but as a simple observation: since “the best and largest part of our subjects of the R.P.R. have embraced the Catholic faith,” the Edict of Nantes had become “useless.” The new text ordered the demolition of all remaining churches, forbade all Protestant worship, and banished all pastors.[09] But it contained a clause of unprecedented cruelty: it forbade laypeople from leaving the kingdom, under penalty of the galleys for men and confiscation of body and property for women.[09] Louis XIV intended not only to eradicate a faith but also to imprison the faithful in a kingdom that had become a prison for them. It was a monumental error, a self-inflicted wound from which his future rival would draw its strength.

Chapter 2: A Brandenburg Wasteland and the Call from Potsdam

Compared to the France of the Sun King, the embodiment of power and glory, the Brandenburg-Prussia of 1685 was a poor relation. Having emerged drained from the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), the electorate was nothing but a field of ruins. The conflict had wiped out nearly half its population, leaving behind fallow lands, depopulated cities, and a shattered economy.[10] Berlin, its capital, was a modest town of 6,000 souls, a far cry from the great European metropolises.[11] The state itself was a mosaic of scattered, disjointed territories.[10] It was in this context of desolation that Frederick William of Hohenzollern, known as the “Great Elector,” reigned.

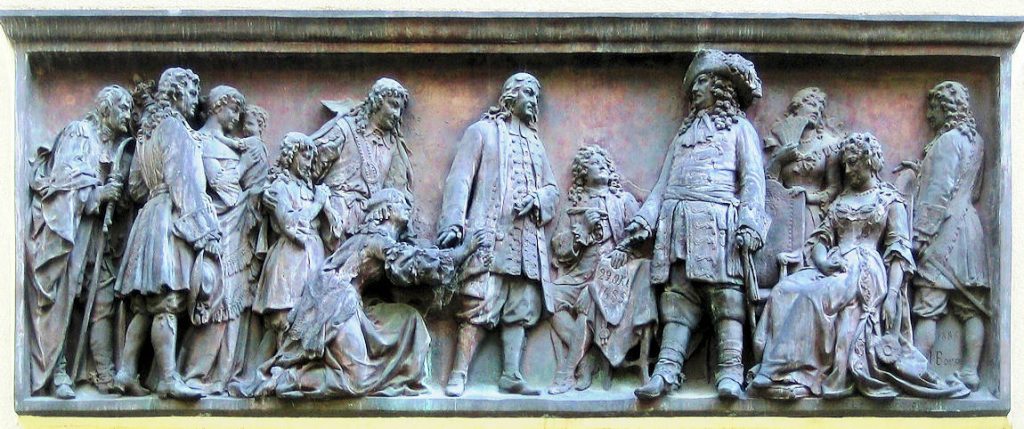

Two men would play a prominent role in shaping the future king: Jacques Rousseau, a Huguenot pastor and teacher who was the tutor of Frederick II, “Frederick the Great,” during his youth in Rheinsberg, and Jacques Duhan de Jandun, a Huguenot of French origin and a learned librarian.

A Calvinist prince ruling over a predomi-nantly Lutheran population, he was a pragmatic statesman whose policy was guided by a clear vision: the reconstruc-tion of his state depended on attracting human capital.[12] Louis XIV’s decision to expel his Protestant subjects was, for him, a historic opportunity. He saw it as a chance to heal the wounds of war by welcoming an educa-ted, skilled, and industrious population that, moreover, shared his own Reformed faith.[13]

Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg, the Great Elector in armor and electoral robe. (1620-1688) — Portrait by Govert Flinck

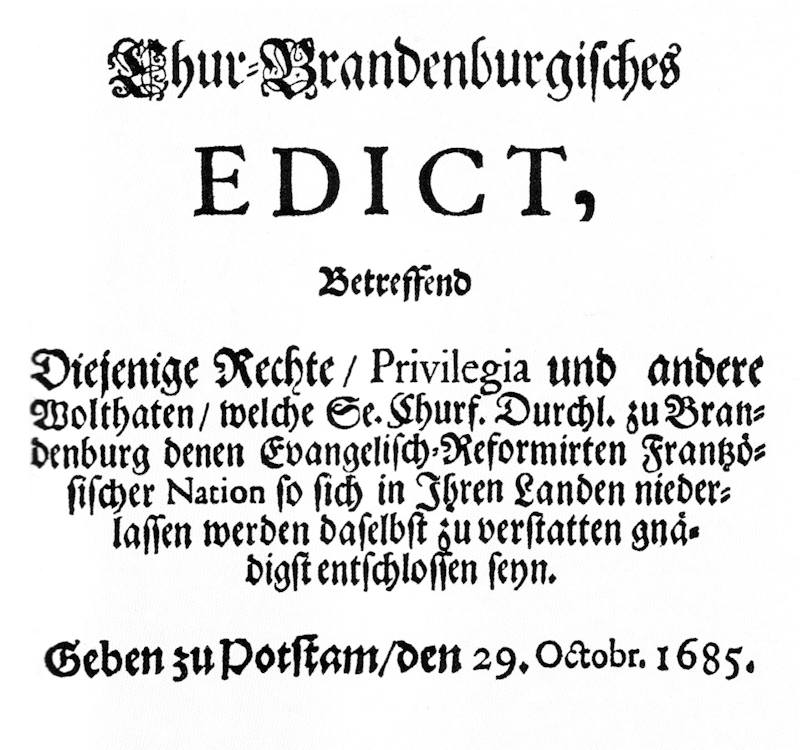

Just eleven days after the signing of the Edict of Fontainebleau, on October 29, 1685, the Great Elector promulgated the Edict of Potsdam. This document is a masterpiece of political marketing. Written in French and German for wide distribution, it did not merely offer vague asylum; it rolled out a veritable red carpet, detailing with almost contractual precision the benefits offered to refugees.[14]

The Edict of Potsdam was a firm and enticing promise. It guaranteed full logistical support, exceptional tax advantages, access to property and housing, immediate economic integration, and legal and religious autonomy. Crucially, it guaranteed freedom of worship in the French language, with their own pastors, and the right to settle disputes before their own judges.[14]

In short, where France offered forced conversion or the galleys, Brandenburg offered freedom, property, and citizenship. It was a direct and irresistible appeal to a persecuted elite.

Chapter 3: The Builders of Berlin: The Impact of the Huguenot Refuge

The call from Potsdam was heard. It is estimated that of the approximately 200,000 Huguenots who managed to flee France, around 20,000 chose Brandenburg-Prussia.[08] These refugees were, for the most part, from the most productive classes of French society: artisans, merchants, entrepreneurs, intellectuals, and military officers.[13] They arrived from a country that was economically and culturally more advanced, bringing with them invaluable know-how.

Their impact on the Prussian economy was immediate and revolutionary. They established and developed industries that had been non-existent, particularly in luxury textiles, watchmaking, jewelry, and tanning.[15] They introduced new agricultural crops and helped drain the marshes.

The most visible transformation was that of Berlin. The city experienced a population explosion, growing from 6,000 to nearly 30,000 inhabitants in a few decades. Around 1700, one-third of Berlin’s population was of French origin.[11] The Huguenots were not simply absorbed; they formed a veritable “colony” with its own institutions. They built their churches, the most emblematic being the impressive French Cathedral (Französischer Dom) on the Gendarmenmarkt square, erected from 1705.[16] They founded their schools, like the prestigious Collège Français in 1689, their hospitals, their courts,[11] and also their cemetery.

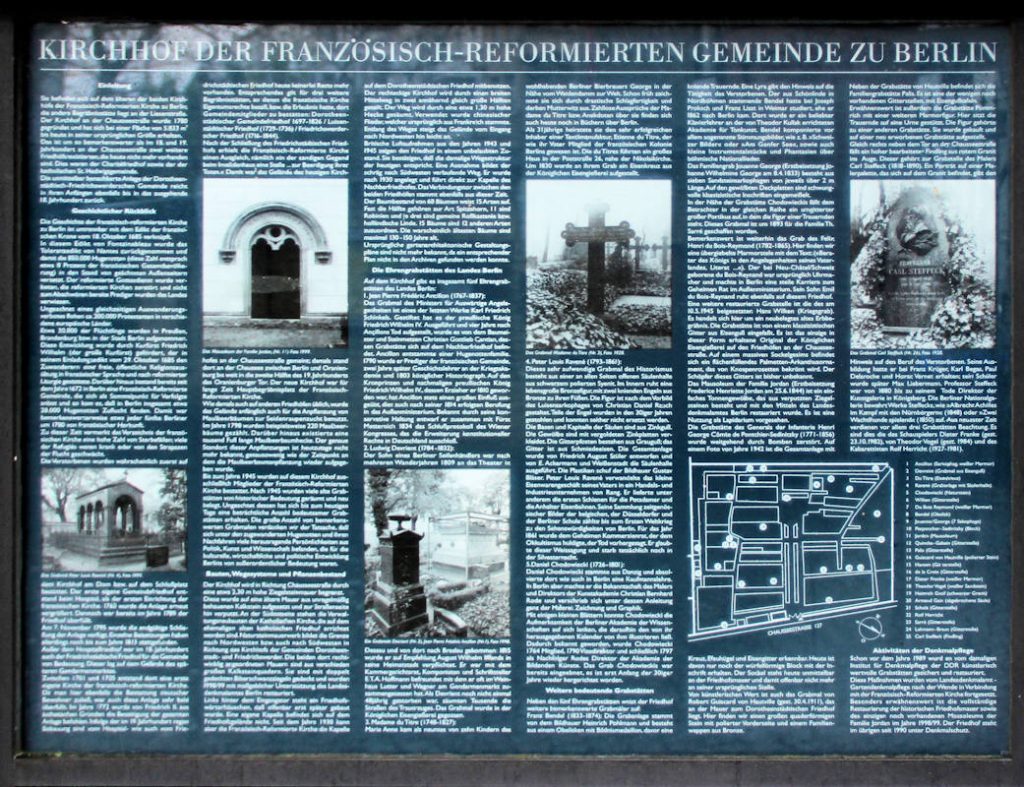

The first cemetery for the Reformed community was opened in Berlin in 1780 for the descendants of Huguenots and Protestants of French origin. This French cemetery in Berlin (division I) (Französischer Friedhof I) is located in the Oranienburg suburb of Berlin-Mitte. It is a unique example of the neoclassical style that was in vogue at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. On the column are two inscriptions: “To its members who died for the King and the Fatherland, the French Church of Refuge in Berlin” inaugurated “on September 2, 1876” and “I am faithful until death and will give you the crown of life.”

A second French cemetery, the French Cemetery in Berlin (Division II). (Französischer Friedhof II) was opened in 1835. Theodor Fontane is buried there. There are several monuments commemorating those who died in wars:

- 1864: The War of the Duchies, also known as the Second Schleswig War or the Second Prussian-Danish War;

- 1866: The Austro-Prussian War, a conflict in 1866 between Prussia, supported by Italy, and Austria, backed by the main states of the German Confederation (Baden, Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony, Hanover, Hesse), which ended in victory for Prussia and Italy. Essentially political, this conflict, desired by Bismarck, was intended to force Austria to relinquish its position of dominance (Machtstellung) in Germany to Prussia. The war was triggered by a dispute between Vienna and Berlin over the administration of the Danish duchies. The Treaty of Prague (August 23, 1866) sanctioned the reorganization of Germany according to Prussian views. Through the Treaty of Vienna (October 3, 1866), Italy, thanks to the arbitration of Napoleon III, received Veneto.

- of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and

- of the Great War. The violent fighting in 1945 damaged much of the cemetery. In 1961, during the construction of the Berlin Wall by the GDR, the chapel and the pastor’s house were destroyed.

Cemetery I of the French Reformed Community, Chausseestraße 126, Berlin-Mitte

Beyond the economy, the Huguenots’ contribution was political. Raised in the ideolgy of an absolute monarchy, they showed unwavering loyalty to the Hohenzollern dynasty. Having no ties to the local landed aristocracy (the Junkers), they provided the central government with a body of devoted civil servants and military officers, an ideal instrument for forging a centralized and efficient administration.

Chapter 4: Irony in Uniform: From the Revocation to the War of 1870

The integration of the Huguenots into Prussia was a spectacular success. Within two centuries, their descendants became loyal Prussians, fully integrated into the army, the administration, and intellectual life.[17] The story of this assimilation culminates in the most tragic paradox of this saga: the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.

When Napoleon III’s France declared war on William I’s Prussia, it faced an army whose officer corps had been partly shaped by its own exiled children. Prussian officers with French-sounding names led German troops to victory against their ancestors’ homeland. The French defeat at Sedan was, in a sense, the distant outcome of the Revocation of 1685.

An emblematic figure of this hybrid identity is Theodor Fontane (1819-1898), one of the greatest German realist novelists. A proud descendant of a Huguenot family, his life and work are a testament to the fusion of French heritage and Prussian identity.[18]

During the war of 1870, he served as a war correspondent and was even captured by French irregulars (francs-tireurs), a poignant confrontation between the descendant of exiles and the land of his forefathers.[19]

Theodor Fontane (1890) — Photo: J. C. Schaarwächter

Today in Berlin, the Huguenot Museum (Hugenottenmuseum), housed within the French Cathedral, preserves the memory of this history.[20] It tells the story of how one nation’s quest for absolute unity became the source of another’s strength.

Act II: The Spirit of the Enlightenment – The Weapon of Prussian Reason (1740-1789)

The Enlightenment was an era of culmination, recapitulation, and synthesis—not radical innovation. At its foundation were the notions of autonomy, the human purpose of actions, and universality. Three simple ideas whose countless consequences intertwine and weave the true spirit of the Enlightenment. (BNF)

Chapter 5: The Philosopher-King and the Patriarch of Ferney: The Potsdam Dialogue

If the blood of the Huguenots nourished Prussia’s body, the spirit of the French Enlightenment sharpened its mind. In the mid-18th century, Frederick II, known as “Frederick the Great,” ascended the Prussian throne with the ambition of transforming his kingdom. The son of Frederick William I—the “Soldier King”—and Sophia Dorothea of Hanover, he was born on January 24, 1712, during the reign of his grandfather, Frederick I.

A passionate Francophile, he preferred the French language and philosophy to those of his own country, which he considered barbaric.[21]

The leading figure of this movement was Voltaire. For Frederick, he was the incarnation of the genius of the Enlightenment.

Their correspondence, spanning more than forty years, is a monument of European intellectual history.[22] It began in 1736, when the young crown prince wrote to the philosopher to request his mentorship.

This relationship reached its zenith between 1750 and 1753, when Voltaire finally accepted the king’s invitation and moved to the Sans_Souci Palace in Potsdam.[23] It was a summit dialogue between power and intellect. There, Voltaire corrected the king-poet’s French verses and participated in philosophical debates.[23] However, the alliance was short-lived. Voltaire, a free spirit, quickly understood that he was more an instrument of the king’s glory than an advisor. The famous quote, attributed to Frederick, “You squeeze the orange and throw away the peel,” summarizes their relationship.[24]

François-Marie Arouet, known as Voltaire (1724 or 1725), after Nicolas de Largillierre, on display at the Palace of Versailles.

The break became inevitable, and Voltaire left Berlin in 1753, not without being humiliated by the king, who had him briefly arrested in Frankfurt.[25]

Chapter 6: Reason of State in the Service of Prussian Power

Frederick II was no naive disciple of the Enlightenment. He was a strategist who understood how to instrumentalize the new philosophy. He separated the methods of reason and efficiency from the morality of liberty and equality. He adopted the former to strengthen his state and rejected the latter.

By proclaiming himself the “first servant of the state” (erster Diener des Staates), he secularized power.[26] The monarch’s legitimacy no longer derived from God but from his usefulness to the collective, an idea laid out in his work Anti-Machiavel.[27] Guided by this principle, he reformed the judicial system, abolished torture (except for high treason), and rationalized the administration.[28] Economically, he pursued a mercantilist policy to maximize state revenue.[28]

But it was in the military sphere that the application of reason was most spectacular. Inheriting an already disciplined army, Frederick transformed it into a formidable war machine, innovating in tactics and logistics.[29] However, this “enlightenment” had its limits. While Frederick II promoted religious tolerance, declaring that in his kingdom, “everyone must find salvation in his own way,” this freedom ended where criticism of power began.[30] The rigid social structure, dominated by the Junkers, and the institution of serfdom were never challenged.[28] “Enlightenment” was a tool for perfecting the state machine, not a right granted to the people.

Chapter 7: Diverging Destinies: Versailles Declines, Prussia Is Forged

The second half of the 18th century saw the destinies of France and Prussia diverge. While Prussia consolidated itself, the French monarchy entered a period of decline, paralyzed by an unjust tax system and a society of privilege.[31] France went into debt for distant wars like the American War of Independence, while Prussia methodically perfected its state apparatus.

The French Revolution of 1789 had a paradoxical effect in Germany. The invasion by revolutionary and later Napoleonic armies, despite the Prussian defeat at Jena in 1806, delivered a salutary shock.[32] The French revolutionary universalism, perceived as a foreign occupation, fueled a nascent German nationalism in reaction.[17] This new nationalism found its champion in the Prussian state, which had already modernized itself, partly thanks to the lessons learned from the France of the Enlightenment.

Today, the architecture of Potsdam bears witness to this. The Sans-Souci Palace, with its intimate Rococo style, symbolizes Frederick’s fascination with the French spirit.[23] But at the other end of the park stands the Neues Palais (New Palace), a colossal edifice.[33] Frederick the Great had it built just after the Seven Years’ War, not to live in, but as a “fanfaronnade” (a boast) to prove to Europe that Prussian power was intact.[34] These two palaces are the two faces of Prussian enlightened despotism, monuments built in a French intellectual language.

Conclusion: The Broken Mirror of Berlin

The history of Berlin, seen through the prism of its ties to France, is that of a broken mirror. It reflects an image of France where its greatest strengths—its cultural unity and its intellectual genius—were turned against it. The two acts of this historical drama, the exile of Huguenot blood and the export of the Enlightenment spirit, reveal a disquieting truth: a nation can, through its own contradictions, become the unwitting architect of its rival’s power.

The act of the Revocation was a tragedy of certainty. In his quest for absolute unity, Louis XIV confused homogeneity with strength. The French Cathedral on Gendarmenmarkt is not just a place of worship; it is a monument to France’s miscalculation, a cornerstone of Berlin laid by Paris.

The act of the Enlightenment was an irony of influence. France exported a philosophy of reason that Frederick II brilliantly diverted to strengthen an authoritarian and militaristic state. The Sans-Souci Palace is not just a Rococo gem; it is the laboratory where French intelligence was distilled to fuel the Prussian war machine.

Thus, Berlin stands as the repository of a paradoxical French memory. Every street name of Huguenot origin, every palace room imbued with the spirit of Voltaire, tells the story of how France gave Germany, through exile and intellect, the instruments of its own greatness. It is a powerful lesson of history, engraved in the marble and bronze of the German capital: the consequences of a nation’s actions often escape its control, and history, in its cruelest twists, sometimes turns our greatest gifts into the weapons of our future adversaries.

Joël-François Dumont

Sources

[01] Bluche, François. Louis XIV. Fayard, 1986. This reference work provides an in-depth analysis of the concept of the monarch’s absolute and divine power..

[02] Garrisson, Janine. L’Édit de Nantes et sa révocation : Histoire d’une intolérance. Éditions du Seuil, 1985. The book explores the political logic leading from enforced tolerance to persecution.

[03] Musée Protestant. “La Révocation de l’édit de Nantes (1685)“. Musée Protestant.

[04] Fumaroli, Marc. Le Poète et le Roi : Jean de La Fontaine en son siècle. Éditions de Fallois, 1997. The author describes the “strict” interpretation of the edict as a legal tool for eroding Protestant rights..

[05] Laborie, E. “Les dragonnades et l’exil des protestants poitevins”. Société des Antiquaires de l’Ouest, 1913. Study on the measures of persecution preceding the Revocation.

[06] Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Dragonnades“. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

[07] Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel. L’Ancien Régime, tome 1 : 1610-1715. Hachette, 1991. The historian details the demographic and economic crises of Louis XIV’s reign.

[08] Magdelaine, Michelle et von Thadden, Rudolf (dir.). Le Refuge huguenot. Armand Colin, 1985. Une analyse de l’impact démographique et économique de l’exil huguenot.

[09] Gouvernement français. “Édit de Fontainebleau (1685)“. Archives de France. Transcription of the original text.

[10] Clark, Christopher. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Penguin Books, 2007. A history of Prussia detailing the state of the electorate after the Thirty Years’ War.

[11] Ribbe, Wolfgang (dir.). Geschichte Berlins. C.H. Beck, 2002. Reference work on the history of Berlin, including its demographic evolution.

[12] Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg“. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

[13] Jersch-Wenzel, Stefi. “Die Einwanderung der Hugenotten in Preußen”. Francia, vol. 13, 1985, pp. 243-260. Analysis of the Grand Elector’s reception policy.

[14] Deutsches Historisches Museum. “Das Edikt von Potsdam (29. Oktober 1685)“. Deutsches Historisches Museum. Transcription and analysis of the edict.

[15] Muret, Eduard. Geschichte der Französischen Kolonie in Brandenburg-Preußen. Scherer, 1885. A classic study of the economic impact of the Huguenots.

[16] Französischer Dom Berlin. “Geschichte“. Französischer Dom Berlin.

[17] Gaxotte, Pierre. Frédéric II. Fayard, 1967. The book discusses how Prussia utilized the talents and loyalty of the descendants of Huguenots.

[18] Theodor Fontane Gesellschaft. “Biographie“. Theodor Fontane Gesellschaft.

[19] Fontane, Theodor. Kriegsgefangen. Erlebtes 1870. R. v. Decker, 1871. Account of his captivity during the Franco-Prussian War.

[20] Hugenottenmuseum Berlin. “Das Museum“. Hugenottenmuseum Berlin.

[21] Mitford, Nancy. Frederick the Great. Hamish Hamilton, 1970. A biography that abundantly illustrates the king’s Francophilia.

[22] Voltaire Foundation. “The Correspondence of Voltaire and Frederick the Great“. University of Oxford.

[23] Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg. “Sans-Souci Palace“. SPSG.

[24] Pomeau, René. Voltaire en son temps. Fayard, 1995. A monumental biography detailing the relationship between Voltaire and Frederick II.

[25] MacDonogh, Giles. Frederick the Great: A Life in Deed and Letters. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2001. Analyse la rupture entre le roi et le philosophe.

[26] Ritter, Gerhard. Frederick the Great: A Historical Profile. University of California Press, 1968. Analyze Frederick II’s conception of the state.

[27] Frederick II of Prussia. Anti-Machiavel ou Essai de critique sur le Prince de Machiavel. 1740. A work in which he sets out his vision of the enlightened ruler.

[28] Blanning, T. C. W. Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. Random House, 2016. Décrit en détail les réformes administratives, judiciaires et économiques.

[29] Duffy, Christopher. The Army of Frederick the Great. Hippocrene Books, 1974. Ouvrage de référence sur l’armée prussienne du XVIIIe siècle.

[30] Asprey, Robert B. Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma. Ticknor & Fields, 1986. Quotation and analysis of the famous phrase on religious tolerance.

[31] Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press, 2002. Analyzes the structural causes of the decline of the Ancien Régime.

[32] Forczyk, Robert. Iena 1806: The Apogee of Napoleon. Osprey Publishing, 2021. Study of the Prussian defeat and its consequences.

[33] Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg. “New Palace“. SPSG.

[34] Mielke, Friedrich. Das Neue Palais in Potsdam. Propyläen, 1980. Architectural and historical study of the palace as a symbol of Prussian power.

See Also:

- « Berlin, mémoire de France (1) » — (2025-0924)

- « Berlin, Gedächtnis Frankreichs (1) » — (2025-0924)

- « Berlin, Broken Mirror of France (1) » — (2025-0924)

In depth Analysis:

Let’s explore a central irony of Franco-German history through two key episodes centered in Berlin. The first act describes how Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 caused an exodus of Huguenot talent. Welcomed with open arms by a devastated Prussia, these French artisans, entrepreneurs, and soldiers provided the human and technical capital necessary for its rise. The second act analyzes how Frederick the Great, in the 18th century, imported the spirit of the French Enlightenment, notably through his relationship with Voltaire. He used this philosophy not to liberate his people, but to rationalize his administration and perfect his army.

Thus, through the exile of its blood and the export of its spirit, France paradoxically provided its future Prussian rival with the tools of its own power—a history lesson etched in the stones of Berlin.