The Epstein case now resembles a faulty GPS that takes you around the world – from New York to Saint Petersburg via Florida – only to finally tell you, ‘you have reached your destination’. Western intelligence agencies have apparently discovered that Putin was playing chess while everyone else thought they were playing checkers, turning a few powerful figures into pawns on a shifting geopolitical chessboard… Apparently, when the Russian bear takes out its honey pot, even the world’s leaders forget that it might be an oversized fly trap.

The current Russian regime is a delibe-rately designed kleptocracy. The system is based on a symbiotic nexus between three entities: the FSB security service, organised crime and the SPIEF (Saint Petersburg International Economic Forum). Within this structure, the FSB provides state protection (krysha), the mafia provides the operational force and illicit funds, while the SPIEF, the annual showcase for this ‘mafia state’, provides a facade of international legitimacy. This model was forged through collabo-ration between civil servants, led by Vladimir Putin and surrounded by figures from the criminal world, to take control of strategic assets such as the city’s port.

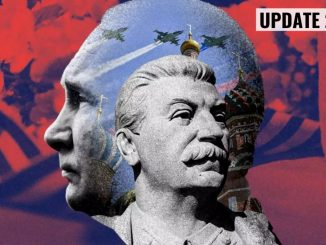

Illustration © European-Security

Once extended nationwide, the system was formalised, transforming the FSB into an economic predator that manages crime rather than combats it. The presence of senior FSB officials on the SPIEF organising committee demonstrates this fusion between security and the economy. The network uses control mechanisms such as kompromat, sometimes obtained through escort networks, to ensure the loyalty of the elite, whether Russian or foreign.

Table of Contents

The St. Petersburg Nexus: The Structural Links between the FSB, SPIEF, and Organized Crime

I. Introduction: The Crucible of the Modern Russian State

The power system of the contemporary Russian state was forged in the crucible of what has been called the “bandit St. Petersburg” of the 1990s. The relationships that formed between the security services, the city’s criminal underworld, and high-level economic forums are not tangential interactions, but constitute the foundation of a system that researcher Karen Dawisha has described as a “kleptocracy.”[01]

Far from being a failed democracy, this system was, from the outset, an “intelligent design” aimed at creating an authoritarian regime led by a close-knit cabal.[01][02]

This report demonstrates that the Federal Security Service (FSB), the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF), and the city’s organized crime syndicates are not distinct entities interacting on an ad hoc basis, but are structurally and symbiotically integrated. In this configuration, the FSB provides the krysha (protection), the mafia provides the operational force and illicit capital flows, and the SPIEF offers a platform for international legitimization, high-level contract negotiation, and networking. This analysis dissects this tripartite structure, showing how it emerged, how it was formalized, and how it operates today, including through informal control mechanisms such as the use of escort networks for kompromat purposes.

The entire system is based on a deliberate blurring of the lines between the legal and the illegal, the state and the private sector, security and crime.

This is not a flaw in the system, but its main feature. Investigations reveal a consistent pattern: state officials, such as Vladimir Putin, collaborate with organized crime figures, such as Vladimir Kumarin and Ilya Traber, on state-sanctioned commercial projects, like the Petersburg Fuel Company (PTK) or the control of the port.[03][04] The security services, whose official mandate is to fight crime,[05][06] have their highest officials deeply linked to this same criminal underworld.[07] A leading economic forum like the SPIEF, organized by the state and its security apparatus,[08] is also described as a venue for illicit networking.[09] This consistency across the three pillars of the investigation indicates that the ambiguity is intentional. It allows for plausible deniability while enabling the network to simultaneously use the tools of the state (legal authority, diplomatic cover) and those of the underworld (violence, illicit finance). The strength of the system lies in its ability to operate in this gray area, making it resistant to conventional pressures, whether judicial or diplomatic.

II. The Genesis of the Network: Power and Crime in 1990s St. Petersburg

A. The Rise of the Tambovskaya Bratva

The Tambov Gang (Tambovskaya Bratva) emerged from the chaos of the Soviet collapse. Founded in 1987-1988 by Vladimir Kumarin, it initially specialized in protection rackets.[10] Its activities quickly expanded to include contract killings, extortion, prostitution, and drug trafficking, all conducted with extreme violence, as evidenced by its bloody clashes with rival gangs, notably the Malyshevskaya gang.[3][10]

In the mid-1990s, the gang underwent a critical evolution, moving from a purely criminal organization to a criminal, commercial, and political enterprise. It shifted to semi-legal and legal activities, particularly the highly lucrative fuel trade, and established private security companies that often served as a front for its coercive activities.[10][11] The leadership of Vladimir Kumarin, also known as Barsukov, was central. His survival of an assassination attempt in 1994, his recovery in Germany, and his regaining control of the gang attest to his ruthlessness and influence.[3][10]

B. The Mayor’s Office as an Incubator for Kleptocracy

The St. Petersburg mayor’s office, under Mayor Anatoly Sobchak, served as an incubator for this new system. Vladimir Putin, then a key official responsible for foreign economic relations, played a central role in setting up schemes to embezzle state assets.[03][12]

Two emblematic cases illustrate this early modus operandi:

- The “Oil for Food” Scandal: An investigation by city councilor Marina Salye revealed that contracts signed by Putin to export raw materials, supposedly to finance food imports for a city on the brink of famine, resulted in the disappearance of over $100 million with no food ever arriving.[12][13] This case demonstrates the early use of front companies and the diversion of public resources for private enrichment.

- The “Twentieth Trust” Affair: A federal investigation led by Andrei Zykov focused on a construction company, Twentieth Trust, registered by Putin’s committee. The company received billions in public funds for projects that were never completed; the money was allegedly diverted to build holiday villas in Spain for Putin and his associates.[12][13][14]

The SPAG affair is a crucial example of the network’s early internationalization. The German real estate company SPAG (St. Peterburg Immobilien und Beteiligungs AG), founded in 1992 with the participation of the St. Petersburg mayor’s office, had Vladimir Putin on its advisory board.[02][3][15] German intelligence services (BND) and prosecutors later investigated SPAG for money laundering on behalf of the Tambov gang and the Colombian Cali drug cartel.[02][15][16] This case establishes a direct link between Putin, the St. Petersburg administration, and international organized crime in a money laundering scheme.

C. Case Study: The Symbiotic Conquest of the Port of St. Petersburg

The control of the St. Petersburg seaport, a strategic asset for both legal and illicit trade, is a perfect microcosm of this nexus.

Its takeover was made possible by an alliance between figures from the security services and organized crime. Viktor Ivanov, a KGB/FSB officer and colleague of Putin, is known for his close ties to the Tambov gang and for supporting Vladimir Kumarin’s war against the Malyshevskaya gang for control of the port.[10][17]

The port then became a hub for trafficking Colombian cocaine to Europe, with logistical support from former KGB officers and mafia groups.[18]

Viktor Petrovitch Ivanov — (Kremlin.ru)

Another key figure in this conquest is Ilya Traber, nicknamed “the Antiquarian,” a powerful associate of the Tambov gang and a personal friend of Putin.[04] Traber acted as an intermediary between the mafia and the political world. At Putin’s request, he appointed another of Putin’s protégés, Alexei Miller, as director of the port.[4] Traber and his associates, such as the Skigin family, took control of key port infrastructure, including the St. Petersburg Oil Terminal (PNT).[19][20]

The St. Petersburg model of the 1990s was not simply a matter of corruption; it was a laboratory for the development of a new form of governance. Rather than passively receiving bribes, officials like Putin and Ivanov actively used their authority to grant licenses, register companies, and direct state power to benefit their criminal partners.[04][10] The goal was not just personal enrichment, but the capture of strategic assets (the port, the fuel market) to build a sustainable economic base for the network. This model proved more effective than simple corruption: the state outsourced violence to its criminal partners, who in return received state protection (krysha) and access to lucrative monopolies. When these figures came to power in Moscow after 2000, they did not abandon this model; they expanded it nationwide.

III. The Formalization of the Nexus: State Institutions as Instruments

A. The FSB: From Shield and Sword to Economic Predator

Officially, the FSB’s mandate is broad, including counterintelligence, counterterrorism, and combating organized crime and corruption.[05][06][21] However, numerous investigations reveal a “symbiosis” between the FSB, political power, and organized crime.[18] The FSB has become a “state within a state,”[18] whose activities largely escape the control of civil society.[05]

The case of Sergey Korolev is emblematic. As the First Deputy Director of the FSB, he is one of the most powerful men in Russia’s security apparatus. An in-depth investigation by OCCRP and iStories documented his deep and ongoing ties to major organized crime figures:[07]

- Gennady Petrov: A central figure in the Tambov gang’s international money laundering operations, arrested during “Operation Troika” in Spain. Spanish wiretaps recorded Korolev, codenamed “Shakefoot,” assisting Petrov.[07]

- Aslan Gagiev (“Big Brother”): A notorious gang leader responsible for at least 60 murders, who claimed that Korolev (then head of the FSB’s Internal Security Directorate) helped him flee Russia.07]

- Oleg Makovoz: A member of another powerful criminal group, with whom Korolev was in communication while his FSB unit was tasked with fighting organized crime.[07]

These elements show that the FSB’s role is not always to eliminate organized crime, but often to manage, control, or partner with it, a phenomenon described as the FSB “covering” for criminal enterprises.[18]

B. The Forum as a State Tool: The Purpose and Power of SPIEF

The St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) was established in 1997 and, since 2006, has been held under the direct patronage and with the participation of the President of the Russian Federation.[22][23][24] Its official purpose is to serve as a leading global platform for business leaders and political figures to discuss key economic issues.22][25] It is a major tool of Russian foreign policy, designed to project the image of a modern Russia open for business and to attract foreign investment.

The forum is organized by the Roscongress Foundation, a socially oriented non-financial development institution.[26][27] Despite this benign description, Roscongress functions as an arm of the state, organizing all major Russian economic forums and facilitating communication between the Russian state and international economic and political elites.[27][28][29]

C. The Organizing Committee: Where Worlds Collide

The composition of the SPIEF organizing committee provides the most direct and obvious structural link between the forum and the security services. The committee list for 2025 [08] includes not only high-ranking ministers (Maxim Oreshkin, Anton Kobyakov) and heads of state-owned corporations (Herman Gref of Sberbank), but also, crucially:

- Sergey Korolev, First Deputy Director of the Federal Security Service (FSB).

- Oleg Klimentiev, First Deputy Head of the Federal Protective Service (FSO).

- Lenar Gabdurakhmanov, Head of the Main Directorate for Public Order Protection of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD).

The presence of the FSB’s second-in-command on the organizing committee of Russia’s main economic forum is a striking illustration of the fusion between security and the economy.

Die Anwesenheit des zweiten Mannes des FSB im Organisationskomitee des wichtigsten russischen Wirtschaftsforums ist eine eindrucksvolle Illustration der Verschmelzung von Sicherheit und Wirtschaft.

| Name | Position on SPIEF Committee | Main Affiliation | Known Links to Security Services |

| Sergei Korolev | Organizing Committee Member | First Deputy Director, FSB | Documented by OCCRP and iStories investigations as having links to Tambov gang figure Gennady Petrov and gang leader Aslan Gagiev.[7][08] |

| Alexander Beglov | Deputy Chairman of the Organizing Committee | Governor of St. Petersburg | Represents the continuity of the St. Petersburg political elite, the cradle of the system.[08] |

| Anton Kobjakov | Executive Secretary of the Organizing Committee | Advisor to the President of the Russian Federation | A key Kremlin official overseeing the forum’s operations, embodying direct state control.[08][30] |

| Oleg Klimentjev | Organizing Committee Member | First Deputy Head, FSO | Represents the direct involvement of the presidential security service in the forum’s organization.[08] |

The presence of Sergey Korolev on the organizing committee cannot be explained by simple security needs, which could be handled by lower-ranking officials. His position is a strong signal to participants, both Russian and foreign, about who really holds power and whose interests are protected. The SPIEF is where multi-billion dollar contracts are signed.[23][31] For the sistema, it is crucial to ensure that these contracts benefit the right people.

Korolev’s presence ensures that the network’s interests remain paramount. Furthermore, the gathering of CEOs, politicians, and journalists from around the world [25][32] makes it a prime environment for FSB intelligence, recruitment, and influence operations. The SPIEF is therefore not just a stage for Putin’s speeches; it is an operational environment where the sistema launders its reputation, closes its deals, and gathers intelligence, all under the watchful eye of its security chief.

IV. Control Mechanisms: Kompromat and the Escort Network

A. The Currency of Kompromat in the Russian System

Kompromat—compromising material—is a fundamental technology of power, inherited from the KGB and actively used by the FSB.[33][34] It is used to discredit opponents, ensure loyalty, and control political and business figures. Methods range from fabricating criminal cases, as shown in the film Kompromat based on a true story,[33][35] to the use of poison (Navalny, Skripal) followed by disinformation campaigns.[36]

A classic form of kompromat is the “honey trap,” which uses sexual encounters for blackmail. This KGB tactic remains relevant, as illustrated by the case of the video recordings used to oust Prosecutor General Yury Skuratov in the 1990s, an operation linked to Putin’s rise.[37]

B. Allegations of Escort Networks at SPIEF

Journalistic investigations, notably by The Insider, have reported on the highly organized presence of female escorts at SPIEF.[09] These are not isolated acts of prostitution (an illegal activity in Russia [38]), but a structured phenomenon. Escorts allegedly seek access to private parties and high-level participants, with demand and prices soaring during the forum.[09]

This phenomenon should be analyzed not as mere decadence, but as a potential intelligence gathering and influence operation. Such environments are ideal for identifying vulnerabilities, recording compromising encounters, and establishing informal channels of influence over powerful Russian and foreign participants.

C. Case Study: The Rybka-Deripaska Affair – Kompromat in Action

This case offers a perfectly documented example of how these networks operate. In 2018, opposition leader Alexei Navalny published an investigation based on the social media posts of a Belarusian “escort” and “sex coach,” Anastasia Vashukevich (aka Nastya Rybka).37][39] Her photos and videos documented a 2016 yacht trip with oligarch Oleg Deripaska (a figure with ties to Paul Manafort) and Sergei Prikhodko, a powerful deputy prime minister and senior foreign policy advisor.37][40] They were recorded discussing sensitive topics such as Russian-American relations.[40]

The repercussions were immediate and state-managed. Deripaska sued Rybka for invasion of privacy, and the Russian media censor, Roskomnadzor, immediately acted to block Navalny’s investigation and force Instagram and YouTube to remove the content.[37][41] Rybka was later arrested in Thailand, and then again in Moscow, where she publicly apologized to Deripaska, stating that she was “just a tool.”[42][43] This sequence of events strongly suggests a coordinated effort by the state and an oligarch to suppress damaging information revealed through an escort.

The organized presence of escorts at elite events like SPIEF is not simply a “service industry,” but a component of the sistema’s informal security architecture. It creates a controlled environment of temptation and vulnerability that the FSB can exploit for kompromat and intelligence purposes. The Rybka case shows what happens when this informal system is publicly exposed: the formal state apparatus (courts, censors) is immediately deployed to restore control. This escort network is an unofficial but vital tool for maintaining discipline and gathering intelligence within the elite.

V. Conclusion and Strategic Implications

A. Synthesis: The Architecture of a “Mafia State”

The body of evidence demonstrates that the St. Petersburg model—the fusion of officials, security agents, and criminals to seize and manage assets—was not an aberration of the 1990s, but the successful prototype of the national power structure built under Vladimir Putin.[18][44][45] The FSB, the underworld (embodied by the Tambov gang and its successors), and state-controlled platforms like SPIEF are the three pillars of a kleptocratic regime. This conclusion is consistent with the analyses of eminent scholars such as Karen Dawisha (Putin’s Kleptocracy),[01][46] Catherine Belton (Putin’s People),[47] and Mark Galeotti (The Vory).[48][49]

SPIEF is the annual general meeting and trade show of this system. It is where the network strengthens its ties, launders its reputation on the world stage, and conducts its most important business under the full protection and supervision of the state security apparatus.

B. Strategic Implications for Policy and Intelligence

The analysis of this nexus has direct implications for governments, intelligence agencies, and businesses interacting with Russia:

- Engagement is Compromise: Treating institutions like SPIEF as standard economic forums is a naive approach. The participation of Western companies and officials lends legitimacy to the kleptocratic system and exposes them to the sistema’s intelligence gathering and influence mechanisms.

- Targeting Sanctions: Sanctions should target not only top officials, but the entire network architecture, including mid-level officials, front companies (like those identified in the SPAG and “Troika” cases in Spain), and family members who hold assets.[18][50] The individuals on the SPIEF organizing committee are prime targets for further investigation.

- A Global Network: The money laundering schemes detailed in Germany [03][15] and Spain [10][50] show that the network’s financial operations are deeply integrated into the Western financial system. Combating this phenomenon requires robust international cooperation in anti-money laundering.

- Monitoring the Next Generation: The children of the original St. Petersburg cabal now hold senior positions in major state-owned banks and companies.[18] Tracking their activities is crucial to understanding the future evolution and resilience of the network, which is designed for dynastic succession.

Joël-François Dumont

See Also:

- « Der Honigtopf von Sankt Petersburg und der russische Mafia-Staat » — (2025-0722) —

- « The St. Petersburg Honey Trap and the Russian Mafia State » — (2025-0722) —

- « Медовий горщик Санкт-Петербурга і російська мафіозна держава » — (2025-0722) —

- « Le piège à miel de Saint-Pétersbourg : l’État-Mafia russe » — (2025-0722) —

Notes

- [01] Dawisha, Karen: Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? Simon & Schuster, 2014. Reference work analysing the formation of a kleptocratic regime by Putin’s circle in Saint Petersburg.

- [02] Belton, Catherine: ‘The SPAG Affair: The Case That Reveals Putin’s System’. Article analysing the case of the real estate company SPAG and its links to money laundering and organised crime. Often discussed in connection with her book Putin’s People.

- [03] The Insider: ‘The St. Petersburg Connection’. A series of investigations into the links between officials in the St Petersburg city administration, including Putin, and organised crime in the 1990s.

- [04] OCCRP (Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project): ‘The Antiquarian’. Investigation into Ilia Traber, his links to Putin and his role in the takeover of strategic assets.

- [05] Federal Law of the Russian Federation of 3 April 1995 No. 40-FZ: ‘On the Federal Security Service’: Legislative text defining the legal status, tasks and powers of the FSB.

- [06] Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of 11 August 2003 No. 960: ‘Issues relating to the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation’. Document specifying the structure and functions of the FSB.

- [07] iStories & OCCRP: ‘“Shakefoot” and “Big Brother”: How a Top FSB General Became a Point Man for Russia’s Criminal Underworld’. Major investigation documenting Sergei Korolev’s links with Russian mafia bosses.

- [08] Roscongress Foundation: ‘St. Petersburg International Economic Forum Organising Committee’. Official list of members of the SPIEF organising committee.

- [09] The Insider: ‘Girls are a must: How the St. Petersburg Economic Forum became a showcase for the elite escort market.’ Investigative article on the organised presence of escort networks at SPIEF.

- [10] Galeotti, Mark: The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia, Yale University Press, 2018. Detailed analysis of the Russian mafia, including the history and operations of the Tambov gang.

- [11] Volkov, Vadim: Violent Entrepreneurs: The Use of Force in the Making of Russian Capitalism. Cornell University Press, 2002. Sociological study of the role of criminal groups and private security agencies in the post-Soviet Russian economy.

- [12] Salye, Marina: Report of the St. Petersburg City Council Investigation Commission, 1992. Discussed in detail by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- [13] Belton, Catherine: Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020. A book documenting in detail the patterns of corruption in Saint Petersburg.

- [14] Zykov, Andrei: Materials from the criminal investigation into the Twentieth Trust company. Saint Petersburg Times.

- [15] Der Spiegel: Investigative articles on the BND investigations. Example: ‘The Putin System’.

- [16] Prosecutor in Darmstadt, Germany. (The Times).

- [17] The Jamestown Foundation: Profile of Viktor Ivanov.

- [18] Galeotti, Mark: ‘The FSB and the Mafia: A Story of a Symbiotic Relationship’. Article analysing the merger between the security services and organised crime in Russia.

- [19] Novaya Gazeta: Investigations into the privatisation and control of the Saint Petersburg oil terminal (PNT).

- [20] Files from the Spanish criminal investigation ‘Operation Troika’. (El País).

- [21] Official website of the Federal Security Service (fsb.ru), describing the organisation’s missions.

- [22] Official website of the St Petersburg International Economic Forum (forumspb.com): ‘About the Forum’ section.

- [23] TASS, RIA Novosti. Annual reports on the results of the SPIEF. (TASS).

- [24] Official website of the President of Russia (kremlin.ru). Press releases on the SPIEF.

- [25] Roscongress Foundation: Annual reports on the SPIEF.

- [26] Official website of the Roscongress Foundation (roscongress.org): Presentation of the foundation.

- [27] RBC (RosBiznesKonsalting): Role and financing of the Roscongress Foundation.

- [28] Kommersant: Expansion of Roscongress’s role.

- [29] The Bell: Investigations into Roscongress’s governance structure.

- [30] Official website of the Kremlin (kremlin.ru). Official biography of Anton Kobiakov.

- [31] Reuters, Bloomberg.Numerous economic articles reporting on the main agreements. (Reuters).

- [32] Lists of participants and media partners published on the official SPIEF website.

- [33] Press service for the film Kompromat (2022): Press kit explaining the context of the film.

- [34] Soldatov, Andrei, and Irina Borogan: ‘The New Nobility’. PublicAffairs, 2010.

- [35] Le Figaro: ‘The incredible story of Yoann Barbereau, the Frenchman who inspired the film Kompromat’.

- [36] Bellingcat: Investigative reports on the poisoning of Alexei Navalny.

- [37] The Guardian: Articles covering the Skuratov case and the Rybka-Deripaska case.

- [38] Code of Administrative Offences of the Russian Federation: Article 6.11.

- [39] Navalny, Alexei. ‘Yacht, Oligarch, Girl: A Tale of Bribery for a Vice Premier’: Video investigation.

- [40] The Washington Post: ‘A Russian oligarch, a vice premier and a yacht trip: A new Navalny video rocks Moscow’.

- [41] Meduza: Reports on Roskomnadzor’s actions.

- [42] Reuters: ‘“I’m sorry for Oleg Deripaska”: Belarus model in Russia sex tape says.’

- [43] Associated Press: Media coverage of Rybka’s arrest.

- [44] Harding, Luke: Mafia State: How One Reporter Became an Enemy of the Brutal New Russia. Guardian Books, 2012.

- [45] Aslund, Anders: Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy. Yale University Press, 2019.

- [46] The Economist: Review and analysis of the book Putin’s Kleptocracy.

- [47] Financial Times: Review and analysis of the book Putin’s People.

- [48] Foreign Policy: Articles by Mark Galeotti on the concept of the ‘mafia state’ in Russia.

- [49] Raam op Rusland: Analyses and publications by Mark Galeotti on organised crime and the Russian security services.

- [50] El País: Articles detailing the findings of the Spanish investigation ‘Operation Troika’