The appeal of the Russian market, perceived as an El Dorado by Westerners, stems from a historical strategic blindness. For centuries, the West has deluded itself into believing that trade can integrate Russia as a rational and peaceful player in the global economy.

However, this vision is fundamentally flawed. For the Kremlin, from the Tsarist era to the present day, trade is not an end in itself, but a pure instrument of power. It is a means of acquiring technology and capital to strengthen its military apparatus and consolidate its regime, while weakening its adversaries.

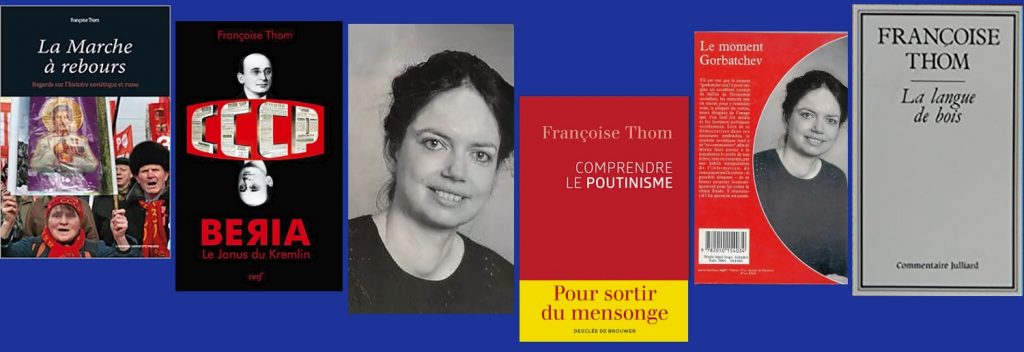

As historian Françoise Thom demonstrates, Russia tirelessly repeats a “cycle of predation”: it attracts foreign investors to modernize, then plunders or expels them once its objectives have been achieved.

The West, confusing its own hopes with Russian reality, has thus continually financed its own adversary. It has never understood the Kremlin’s strategy of disguising its quest for power as economic cooperation. Lenin cynically summed it up: “The capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.” Editor’s note

In a masterful essay, Françoise Thom dissects a little-known weapon in the Kremlin’s hybrid war against the West: economic exchanges. She demonstrates that, from the founding of the Bolshevik state, Lenin and the communist leaders who followed him deliberately exploited the greed and stupidity of Westerners to strengthen the power of the communist regime, while sooner or later depriving them of their expected profits. Will it be any different for the Trump administration and American businessmen? (DeskRussie)

I. The Leninist Imprint

Table of Contents

by Françoise Thom in Desk Russia — Paris, September 11, 2025 —

In early March 2022, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio raved about the “extraordinary opportunities,” both economic and geopolitical, that would be available to the United States and Russia once the war in Ukraine was over. In a significant move, on August 15, 2025, during the meeting in Alaska, President Putin signed a decree paving the way for the return of the American company ExxonMobil to the strategic Sakhalin-1 gas and oil project. The post-war Russian-American economic projects under discussion focus on two strategic sectors: energy and rare minerals. Joint oil and gas exploration projects in the Arctic region are at the forefront. There is talk of potential US participation in Gazprom PJSC projects, which could revive stalled initiatives such as Nord Stream 2.

U.S. involvement in Russian natural gas deliveries to Europe would represent a major turning point in energy diplomacy. Perhaps the most controversial project is a proposed U.S. control of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, currently under Russian occupation. This facility, which produced 20% of Ukraine’s electricity before the war, would be managed by the U.S. and its electricity output distributed to both Russia and Ukraine.

The second pillar of potential cooperation focuses on rare earths and critical metals, resources that are essential for clean energy transition and advanced manufacturing. China currently dominates this sector, accounting for 60% of global rare earth production, while Russia has significant untapped reserves. U.S. investment in Russia’s Tomtor deposit in Yakutia is seen as a strategic opportunity to counter China’s stranglehold on the market.

This deposit holds about 19% of the world’s reserves of niobium, an essential element for aerospace alloys and superconducting magnets. Development of the site was halted in 2022 when sanctions blocked access to Western extraction technologies. An estimated $2 billion in infrastructure investment is needed before large-scale operations can begin.

Entranced by these prospects, the Trump administration was led it to side with Russia in the Russian-Ukrainian war and to block any serious measures that might harm Moscow. However, before throwing themselves headlong into “the vast Russian market,” U.S. officials would do well to consider the repeated misfortunes of those who have been caught in the trap of economic cooperation with Russia. A historical retrospective presented here (and in Part II to follow) may serve as a warning to those who are listening to the siren song of the Kremlin.

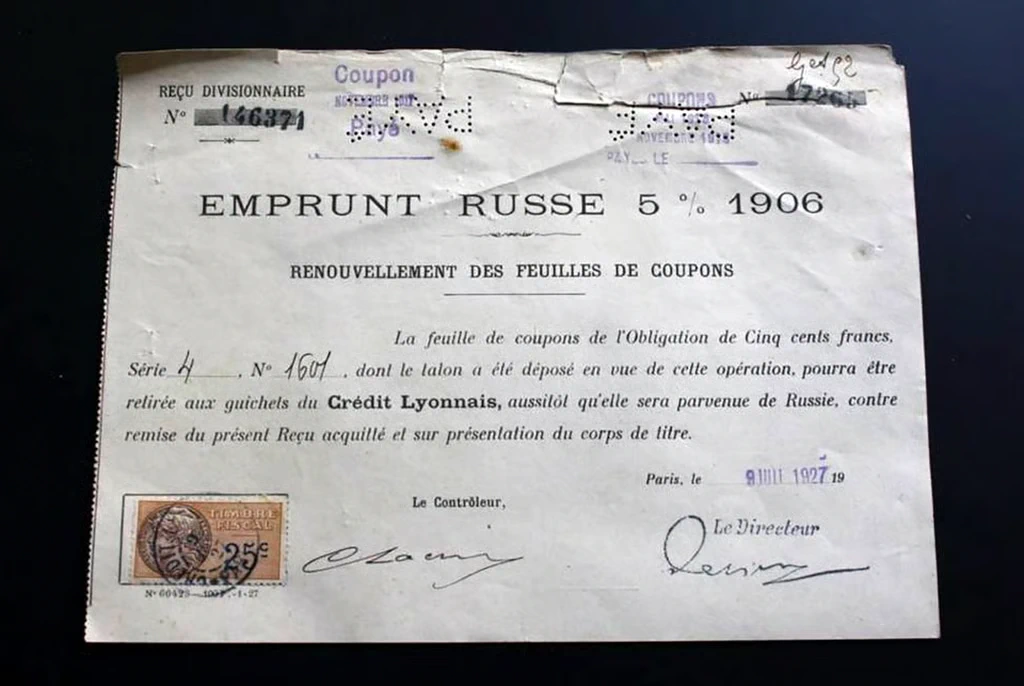

Prelude

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, in the euphoria of the Franco-Russian alliance, more than 1.5 million French savers, encouraged by French banks and the French government, invested heavily in the debt of the Tsarist Empire, amounting to a whopping 15 billion gold francs. These investments, promoted by major banks such as Crédit Lyonnais, offered attractive returns and were perceived as “safe and worry-free.” In the spring of 1906, following a disinformation campaign on the state of Russia led by a venal press generously financed by the Russian government, France had lent 2.2 million gold francs to Nicholas II to reward him for embarking on “democratic reforms.[01]

” Russian securities accounted for a quarter of French investments outside the country before the war, and four-fifths of Russia’s public debt was held in Paris. In total, French capital financed a substantial part of the modernization of the Russian Empire, notably its railways, its industrialization, and the development of its oil industry in Baku. In 1914, France was Russia’s largest creditor.

In January 1918, the Bolshevik government repudiated all foreign debts incurred by the tsarist regime. In one fell swoop, the savings of 1.6 million French bondholders, representing 15 billion gold francs, were wiped out.[02] This was a major financial and psychological trauma in France.

“We have failed to restore Russia to sanity by force. I believe we can save her by trade. Commerce has a sobering influence in its operations. (…) We must fight anarchy with abundance.[03] ”This is how British Prime Minister Lloyd George justified his decision to abandon the policy of armed intervention in Bolshevik Russia in March 1920, when the defeat of the White armies was no longer in doubt. This sentence sums up the huge misunderstanding between the Kremlin and Western democracies in their conception of trade and international cooperation. Westerners imagined that the Bolshevik leaders sought the prosperity of their subjects just as the leaders of democracies did. Whereas for Lenin and his successors in the Kremlin to this day, economic exchanges have only one purpose: to strengthen their power and paralyze their Western adversaries—in short, to improve the balance of power in favor of the camp led by Moscow.

“Exploit the greed of the capitalists” (Lenin)

“Foreigners are already buying off our officials with huge bribes and ‘exporting the remains of Russia’. And they will continue to do so. Our monopoly [on foreign trade] is a polite warning: ‘My dear friends, the time will come when I will hang you for this.’ Foreigners, knowing that the Bolsheviks are not joking, take this seriously. (…) We cannot trade freely: it would be the death of Russia.”Lenin, Letter to Kamenev, March 3, 1922

From the very first months of Lenin’s regime, manipulation of business circles was an important lever in Russian influence policy. Bolshevik Russia was then in an extremely precarious position, caught between the Central Powers, ready to resume the offensive, and the Entente, embittered by Russia’s defection. From the spring of 1918, after the Brest-Litovsk agreements, Lenin’s tactic was to get the “imperialists” on both sides interested in the survival of the Bolshevik government. The situation was more favorable to the Bolsheviks than the state of their economy would suggest.

Count Mirbach, the Reich’s ambassador, believed that Bolsheviks should be supported at any cost, because “if they fell, their successors would work with the Entente to retake the territories that had seceded, Ukraine in particular, and to revise the Treaty of Brest…[04] ”For his part, French Ambassador Joseph Noulens was of the opinion that Russia could only “emerge from nothingness under foreign influence [05] ”and therefore “despite the disappointments Russia has given us, we must not abandon our position, because it would be taken over permanently by others, without any hope of ever recovering the billions we have invested”{06] (April 3, 1918). The French were haunted by the fear that Bolshevik Russia would fall into the German sphere of influence. There were a few skeptics, such as Louis de Robien, a French diplomat in Petrograd, who wrote in his diary on May 14, 1918: ”The colonization of Russia by the Germans—as by us—seems impossible to me: it is shifting ground on which nothing lasting can be built[07],”but these were isolated voices.

— Photo Archives of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs —

Lenin decided to use foreign capitalists to save his regime (famine and shortages were already rampant after just a few months of Bolshevism) and to use economic bait to better divide the “imperialists.” Faced with a Germany bled dry by the Allied blockade, he hyped the vast Russian market as a carrot. On May 15, 1918, negotiations began for the restoration of German-Russian trade relations. The Bolsheviks explained that they would need credit to meet their obligations to the Central Powers and dangled concessions in Russia. On May 17, Mirbach asked his government for additional funds “to strengthen the Bolsheviks’ position.” A. Ioffe, the Soviet ambassador in Berlin, and Leonid Krasin, the Bolshevik expert on economic issues and future Commissar for Foreign Trade, inaugurated the Soviet (and post-Soviet) practice of organizing industrialists and bankers into a lobby in a “bourgeois” country in order to be able to block the initiatives of the party hostile to Moscow. With a keen understanding of the German business mentality, Ioffe and Krasin posed as “realists,” suggesting that they did not take the revolutionary slogans they proclaimed in public seriously. On July 7, they declared that the Bolshevik government was “prepared to renounce its utopian goals and pursue a pragmatic socialist policy.”[08]

Ioffe was entrusted by Lenin with a fourfold task: to neutralize the military party (Hindenburg and Ludendorff) favorable to the elimination of the Bolsheviks, by appealing to industrialists and bankers interested in “the great Russian market”; to support the revolutionary forces in Germany with money and even arms deliveries; to inform the Kremlin about the situation in Germany; and to sow discord between Germany and Turkey. Thus, under the cover of developing economic cooperation, the Bolsheviks sought to:

- Neutralize the anti-Russian wing of the German government, the highly influential military high command in Berlin;

- Accelerate the subversion of the Reich government by financing revolutionary parties;

- Spy on the German government;

- Lay the groundwork for their future expansion in the Caucasus by sowing discord between Turkey and Germany. To achieve this last objective, the bait would be… the oil in Baku, the stronghold of Bolshevism in Transcaucasia, threatened by the Turks and the British.

On June 30, 1918, Lenin cabled Stalin: ”Ioffe informed us today that (…) the Germans (…] promise not to let the Turks enter Baku, but they want oil. Ioffe replied that we were in complete agreement with the principle of give and take. (…] Try to convey to Chaumian [the Bolshevik leader in Baku] as quickly as possible that we now have the best chance of keeping Baku...[09] ”On July 2, Ioffe promised Germany a quarter of the oil production if Baku remained in Bolshevik hands, in order to break its ties with its Turkish ally. It was a masterstroke: the Bolsheviks had persuaded Berlin to become an instrument of their imperial policy, to the point of compromising the German-Turkish alliance.

While enticing Germany with the promise of lucrative contracts, the Bolsheviks pitted the Central Powers against the Entente for the Russian market. In early May 1918, Lenin dangled concessions in eastern Siberia before the Americans, suggesting that the United States would replace the Reich as Russia’s economic partner and that Germany would be weakened by this economic expansion of the United States in Russia. At this time the Bolsheviks sought to encourage the Americans to neutralize the Japanese threat in the Far East and to break away from the Entente.

After the defeat of the Central Powers, Lenin stepped up his attempts to buy the Entente by tempting it with the prospects of the fabulous Russian market. On March 8, 1919, President Wilson sent William Bullitt on a confidential mission to Russia, who reported the proposals of Chicherin, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs: Russia’s recognition of its financial obligations (a reference to the debts of the Tsarist empire, repudiated by Lenin on January 21, 1918), the resumption of trade relations in exchange for the cessation of hostilities in Russia, and the abandonment of Western support for the anti-Bolshevik forces. The Bolsheviks continued to hold out the possibility of reaching an agreement on the question of the tsarist debts, on condition that the West recognized Bolshevik Russia and revived the Russian economy.

This is exactly the same policy being pursued now with the Trump administration: offering joint exploitation of Russian resources on condition that the United States drop Ukraine, exploiting the American fixation on the Chinese threat, with the Kremlin playing the same double game between Washington and Beijing (Putin has just offered Xi joint projects in the Arctic, the very same ones he had just proposed to Witkoff). The Kremlin imposed draconian conditions on ExxonMobil’s return to the Sakhalin 1 project: ExxonMobil had to not only supply foreign equipment essential to the project, but also actively work to lift Western sanctions against Russia. Moscow demanded that ExxonMobil become a lobbyist for Russia in Washington, using its influence to change U.S. foreign policy in exchange for the return of its assets. ExxonMobil’s efforts were to be supported by the American technology companies involved in the Arctic LNG 2 project, which would make them the direct beneficiaries of sanctions exemptions.

After the defeat of the White armies, the Entente turned to a policy of ”cordon sanitaire.” Clemenceau recommended erecting a “barbed wire fence around Russia” to prevent it from causing harm abroad.[10] The Bolsheviks’ goal then became to break “the united front of the imperialists.” In February 1920, Lenin, Trotsky, Ioffe, and Litvinov made numerous statements to the foreign press extolling the advantages of peace and trade with Russia, suggesting that the Bolsheviks would abandon their policy of subversion in the West (even though they were in the process of fomenting revolution in Germany) if the Entente countries stopped supporting the regime’s opponents in Soviet Russia. Karl Radek was already talking about “peaceful coexistence”: “We believe that capitalist countries can now coexist with a proletarian state.”[11] Lloyd George was eager to believe it. In May, Krasin was invited to London to negotiate a trade agreement, just as the Red Army was preparing its major offensive against Poland, which the Bolsheviks saw as a prelude to revolution throughout Europe.

In July 1920, the Bolsheviks, believing themselves to be on a roll, attacked Warsaw. On August 10, under the influence of Krasin and Kamenev, who had been sent to London on August 4, Lloyd George ruled out aid to Poland and recommended that it accept the armistice offered by the Bolsheviks, even though a few days earlier he had threatened the Soviets with sending the British fleet to the Baltic if they did not halt their advance.[12] Abandoned by England, Poland was saved by France.

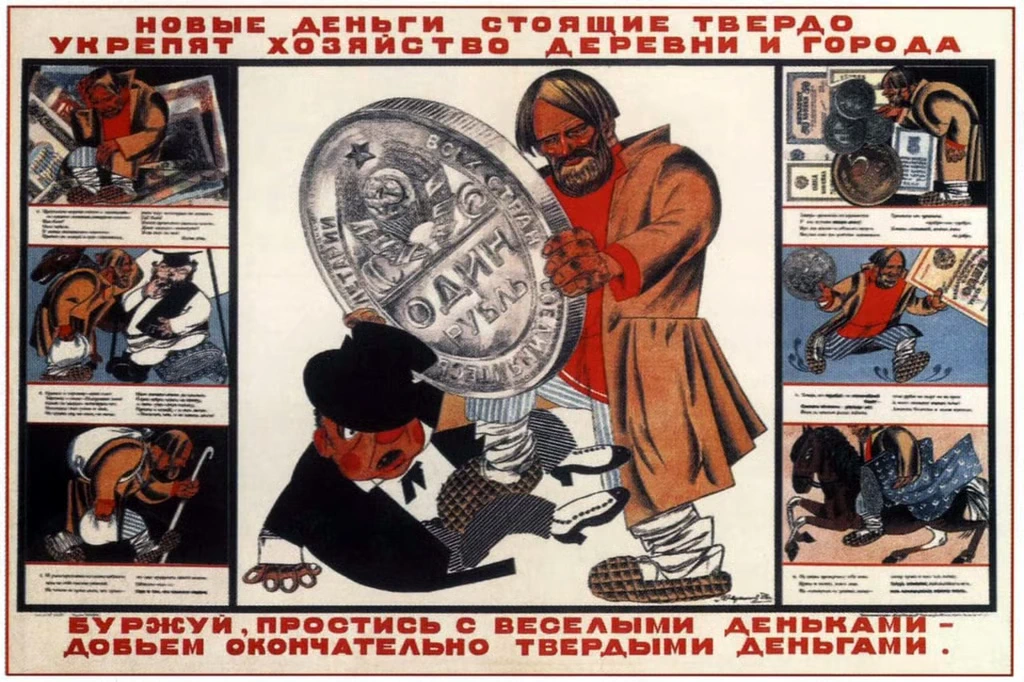

“Building communism with non-communist hands” (Lenin)

When the Anglo-Soviet trade treaty was signed on March 12, 1921, Chicherin was overjoyed. It was a ”turning point in Soviet foreign policy,” he boasted.[13] Moscow killed several birds with one stone. The Entente was undermined because the French took great offense at the Anglo-Soviet agreement, much to the Bolsheviks’ satisfaction. Competition began for the conquest of the Russian market. The Germans rushed into the breach, signing a trade agreement on May 6, 1921. The Reichswehr agreed to develop the Soviet military-industrial complex.

The Bolshevik regime had won, while the country was starving, ruined by requisitions. The capitalists would save Lenin’s Russia. Foreigners were happy to strengthen its power base. Thanks to “economic cooperation,” the bolsheviks were able to create an organized lobby within each capitalist country capable of blocking any initiative contrary to the interests of the Soviet state. Bolshevik Russia gave preference in its orders to countries inclined to support its foreign policy objectives and to ”friendly” firms, in order to motivate the pro-Soviet wing of the bourgeoisie. It placed these relations within a bilateral framework that ruled out concerted action by the Western powers against Moscow. “We must be intelligent, take into account the peculiarities of the capitalist world, exploit the capitalists’ greed for raw materials, and extort from them advantages that will strengthen our economic position among the capitalists themselves, however bizarre that may seem,” Lenin wrote.[14] Lenin had his favorite capitalist, Armand Hammer, who made his fortune in Bolshevik Russia and became the tireless lobbyist for the Soviet regime until Gorbachev. The shrewd man understood the rules of the game: he allowed the Cheka to take control of his first company.[15]

From the summer of 1921, in the midst of the NEP, the Bolsheviks’ main concern was to obtain credit. To this end, Krasin wrote to his deputy Lejava: “We will have to wash and dress presentably, and adopt a more European appearance. If we keep the same look as before, we will get nothing.”[16] But in his view Russia had no need to sacrifice its revolutionary principles to achieve its goals. On November 8, 1921, Krasin wrote to Lenin to dissuade him from going too far in making concessions to the West: “World capitalism will resign itself to the existence of the Soviet system if it is allowed to participate in the exploitation of Russia’s natural resources and labor force15”. The only concession offered by the Bolsheviks was to allow former owners to lease their nationalized businesses and operate them on behalf of the Soviet regime—and even then, in exchange for a large loan. From then on, the economic superiority of the West ceased to be an advantage; on the contrary, it could be turned against the Western camp and used to divide it. Chicherin saw this very clearly: ”The unprecedented originality of our policy lies in the fact that the proletariat is master of political power and offers itself the services of capital without allowing it to become the ruling class”[18] (November 22, 1921).

Returning to the present day, we can see that the Kremlin is splitting the solidarity of the “collective West” by using the instrument of confiscated assets, just as the Bolsheviks waved the vague promise of possible recognition of tsarist debts: those who show complacency toward Moscow are rewarded with the return of a few assets – in exchange, of course, for infinitely more serious concessions. Russia’s offer to allow the United States to use its fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers, the only one of its kind in the world, to support the development of American gas and LNG projects in Alaska would make the U.S. government a customer of a strategic Russian state entity. Since 2009, Russia has been increasing the number of its icebreakers in order to strengthen its position in the Far North, as it vies for dominance with its traditional rivals, Canada, the United States, and Norway, and more recently, China.

“We are going to Genoa not as communists but as merchants” (Lenin)

Toward the fall of 1921, a new project took shape in the West: to create an international corporation for the economic reconstruction of Europe. Among other things, the idea was to allow Germany to exploit Russia’s natural resources and thus pay its reparations. It was agreed to discuss this at the Genoa Conference, scheduled for April 1922. Bolshevik diplomats were immediately mobilized. For Lenin, there was no question of tolerating what looked like a “united front” of capitalists against socialist Russia. In the run-up to the conference, they launched a well-orchestrated campaign to divide Western industrialists. They lured the British with an agreement with Royal Dutch-Shell that would give the company exclusive rights to exploit Baku’s oil. This offer brought the British into conflict with the United States: Standard Oil also had oil interests in the Caucasus. In Germany, they appealed to the very pro-Soviet heavy industry lobby in order to neutralize those who, like Foreign Minister Rathenau, were leaning toward the West. To this end, they sent Radek and Krasin to Berlin, who used all their connections in military, industrial, and financial circles to marginalize the pro-Western wing of the German government. Radek dangled the possibility of the Reichswehr circumventing the disarmament clauses of the Treaty of Versailles by producing weapons and training its men on Soviet soil.

The Soviets attended the Genoa Conference, the first international forum to which they were invited, with very specific intentions formulated by Lenin: “We are going there as merchants because trade with capitalist countries (as long as they have not collapsed) is indispensable to us, and we are going there to formulate the political conditions of this trade to our advantage.” The Western countries were not to be feared because “they are afflicted with the disease of will.” The goal was to prevent the emergence of European solidarity by supporting countries hostile to the Treaty of Versailles, namely Germany and Italy. Lenin recommended misinforming Westerners by toning down ideological proclamations: “No terrible words,” he ordered Chicherin on March 23. ”We must exclude the formula that our historical conception considers world wars inevitable.”

The preliminary work to sabotage the conference bore fruit: on April 16, Germany and Russia signed the Treaty of Rapallo. This success emboldened the Bolshevik leaders (“We must not fear causing the conference to fail,” Lenin telegraphed Chicherin) and pushed them to derail the Genoa conference while seeking other bilateral agreements. The Treaty of Rapallo included secret military clauses: Germany was authorized to set up camps in Russia to test tanks, aircraft, and combat gases (prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles). In exchange, the Germans undertook to build arms industries, the production of which would be shared with Russia. The Soviet government wanted to attract German capital to increase the USSR’s defense capabilities and therefore authorized the creation of secret military bases on its territory.[19] Above all, the Bolsheviks hoped that the Treaty of Rapallo would prevent Germany from joining the League of Nations. This treaty and the Treaty of Berlin of April 1926, which succeeded it, were the levers by which Moscow hoped to prevent Germany from integrating into the Western bloc. By the end of 1923, Germany was already Russia’s leading trading partner. One-third of foreign concessions in the USSR were German, and more than $50 million had been invested in these companies. Not only did German dealers fail to make the expected profits in the USSR, but they even went bankrupt.

In total, more than 350 foreign concessions contributed to the recovery of the Soviet economy during the NEP. By the end of the 1920s, 80% of Soviet oil drilling was carried out using American rotary technology, and all refineries were built by foreign companies. Thanks to this infusion of Western capital and expertise, Soviet production rose from almost zero in 1922 to pre-World War I levels in 1928.

“The strengthening of Stalin’s position stimulated a spirit of tolerance.”[20]

Stalin broke with the NEP in 1928-9. His goal, he said, was the “economic independence” of the USSR.[21] Western investors who had ventured into the USSR were gradually expropriated. The eviction of foreigners was not achieved by a simple decree of general nationalization. Stalin implemented a strategy of gradual suffocation, combining bureaucratic pressure, intimidation, and ideological justifications. Foreign companies were subjected to constant administrative harassment. Exorbitant and retroactive taxes were imposed, import-export rules were changed without notice, and Party-controlled unions launched strikes and made unrealistic wage demands, making it impossible to operate profitably. Propaganda accused foreign specialists and engineers of being saboteurs and spies. The 1928 the Shakhty trial involving Soviet and German engineers created a climate of terror: any technical problem could be interpreted as a malicious counterrevolutionary act, making the position of foreigners untenable. With their backs against the wall, companies had no choice but to negotiate their departure under the worst conditions. The Soviet government offered to “buy back” the concession for a fraction of its real value, presenting this spoliation as a mutually agreed commercial transaction. Refusal meant losing everything and facing criminal prosecution.

These setbacks did nothing to educate Western industrialists. Aware of the USSR’s technological backwardness, Stalin orchestrated a vast program to import skills and capital goods when he launched his five-year plans for accelerated industrialization in order to build an army capable of conquering Europe. Westerners rushed to the USSR. Technical assistance contracts worth millions of dollars were signed with major American and European companies. The achievements of industrialization trumpeted by Stalinist propaganda were in fact the result of this large-scale co-opting of Western business circles.

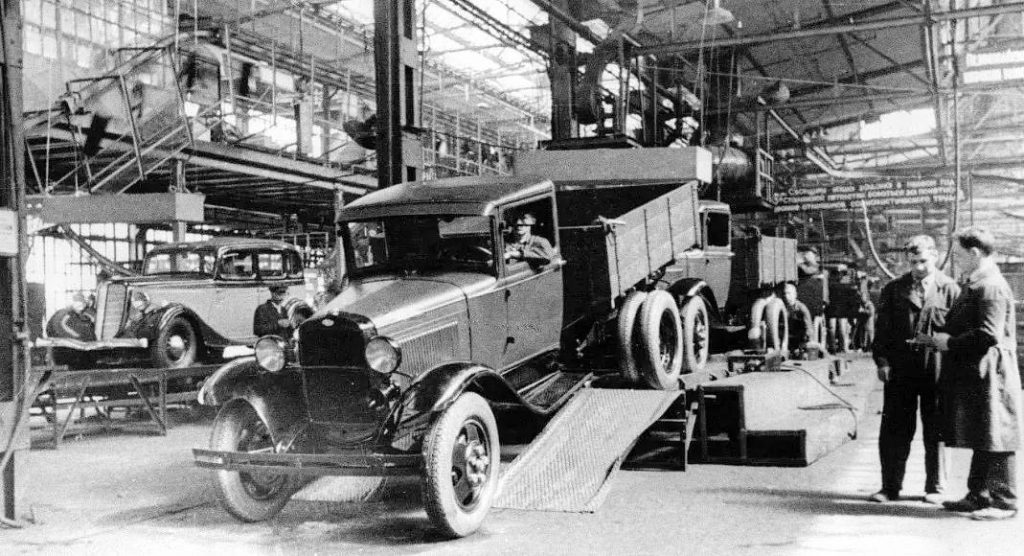

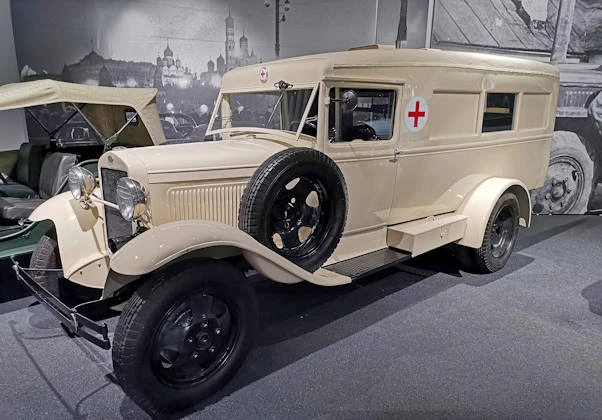

Giants such as Ford played a pioneering role in the creation of the Soviet automotive industry, notably by designing the factory in Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod). General Electric supplied turbines and generators for major hydroelectric projects, such as the Dnieprostroï. The engineering company Albert Kahn, Inc. designed and supervised the construction of more than 520 factories across the USSR between 1929 and 1932, including the tractor factories in Stalingrad and Chelyabinsk. Companies such as McKee Corporation contributed significantly to the construction of steel complexes, such as the Magnitogorsk combine, a symbol of Stalinist industrialization.

Uralvagonzavod embodies this accelerated industrialization: built between 1931 and 1936 in Nizhny Tagil, the factory initially produced tractor wagons, then tanks. Its organization follows American standards, with production lines inspired by Ford and structures designed in the spirit of Albert Kahn. The architecture reflects the spaciousness, modularity, and robustness characteristic of American factories. At the same time, the GAZ factory, which was the result of a contract signed with Ford in 1929, was initially supplied with assembly kits. It also produced the first Soviet vehicles, such as the GAZ-A car (a copy of the Ford Model A) and the GAZ-AA truck (a copy of the Ford AA).

Thousands of engineers, technicians, and skilled workers, mainly American but also German, British, and of other nationalities, were attracted to the USSR. Fleeing the Great Depression that was ravaging the West or motivated by communist convictions, they brought indispensable practical expertise to construction sites and factories, training a new generation of Soviet technical managers. Their fate was often tragic. Many of them were arrested by the NKVD. Their passports were confiscated on arrival, so they could not leave the country. Accused of “sabotage,” they were sentenced to long prison terms, deported to the Gulag camps, or simply executed.

Having squeezed the foreigners dry, Stalin decided he no longer needed them in the mid-1930s. In 1933, six British engineers from Metropolitan-Vickers, who were working on electrical projects, were arrested and accused of sabotage and espionage in a show trial in Moscow. British diplomatic intervention secured their release and expulsion, but the affair marked the beginning of the end for foreign experts.

Stalin resigned himself to this large-scale reliance on foreigners because he was in the process of laying the foundations for the Soviet military-industrial complex. Foreign partners would always be judged in the future on their willingness to strengthen the power sector of the USSR (and later Russia).

In October 1933, Litvinov, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, confided to Hervé Alphand, the French ambassador: “We have always criticized Germany for being concerned only with strengthening relations between our two countries and not with strengthening our international position. We hope that France will pursue a different policy in this regard. [22]” In 1936, when the new French ambassador, Robert Coulondre, presented his credentials to President Kalinin, the latter reminded him that an agreement “is intended to strengthen the defensive power of the signatory parties.” However, the Soviets had not yet obtained anything ”in the field of supplies relevant to national defense.” On the other hand, German industry offered to supply the USSR, on credit, with all the equipment it wanted, ”even weapons,” Litvinov specified.[23]

Around the same time, the Soviets made the Reich’s consent to military orders from the USSR a condition for discussing a new German credit. It was the promise of military technology transfers that prompted Stalin to choose an agreement with Hitler in 1939.[24]

”Winning over influential European economic elites through cooperation”

During the 1960s, Samuel Pisar, President Kennedy’s economic advisor, developed his theory of “convergence” between the USSR and the democracies through trade, which was believed to be an important instrument for guaranteeing peace. This brings us back to Lloyd George’s illusions mentioned above. These were shared by a number of European leaders, such as Chancellor Helmut Schmidt (“Wandel durch Handel” – change through trade, as they say in West Germany) and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing.

Around 1966, the Western camp seemed to be showing centrifugal tendencies that were promising for Moscow. The United States was bogged down in the Vietnam War. France withdrew from NATO’s integrated command, and West Germany moved toward Ostpolitik. Moscow sought détente with both the United States and European countries, for different reasons. With the United States, because it wanted to stabilize its sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. With Europe, it wanted to obtain recognition of the post-war borders, encourage centrifugal tendencies within NATO, and in particular push West Germany toward neutrality, as well as obtain the economic and political advantages of East-West trade, while creating Europe’s energy dependence on the USSR. Washington hoped that, in exchange for economic benefits, the USSR would influence North Vietnam to reach an agreement with Washington that would allow the United States to save face. In the USSR, the economy was going from bad to worse. The import of Western technology and know-how was vital for the survival and modernization of the regime and, above all, for the immense arms build-up undertaken between 1965 and 1970. Brezhnev expected that détente would bring enormous economic gains without the USSR having to sacrifice its global ambitions.

A document found in the East German archives, dated April 26, 1968, at the beginning of détente, outlines the USSR’s long-term European strategy: “eliminate anti-Sovietism and anti-communism through the gradual expansion of political, technological, scientific, and cultural relations; reduce American and West German influence. To this end, the USSR must… rally influential European economic elites through cooperation.”

From 1969 onwards, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik sought to normalize relations with Eastern Europe.

East-West trade was massively supported by a wave of loans granted by Western banks and governments, leading to exponential debt. The FRG used finance as an instrument to foster its industrial power. Its banks focused mainly on financing German industrial exports, making the FRG the USSR’s leading Western supplier.

Willy Brandt

— Photo Bundesarchiv —

France allocated loans for ideological reasons: it hoped to make the USSR a counterweight to the United States. Encouraged by the state as part of de Gaulle’s policy of independence, French banks engaged heavily in preferential loans and purely financial transactions, becoming major creditors to the USSR in order to curry favor with Moscow, without France gaining any significant economic advantage given its poor commercial performance. On the Soviet side, credit-financed trade was primarily aimed at acquiring know-how, particularly dual-use technologies, i.e., technologies with both civilian and military applications, as well as the equipment and factories needed to bridge a technological gap that could cause the USSR to lose the arms race.

Technology transfer took various forms, ranging from the purchase of licenses and patents to the import of advanced equipment. The most spectacular method was the construction of complete “turnkey” factories by Western companies, which brought not only equipment but also engineering, production processes, and staff training to the USSR.

For example, the VAZ-Fiat agreement (1966) involved the construction of a huge automobile factory in a new city, Togliatti.

Italian manufacturer Fiat provided an almost complete transfer of technology: the plans for its modern Mirafiori factory, training for thousands of Soviet engineers and workers, and the license to produce its Fiat 124 model, which became the Zhiguli in the USSR.

Another colossal project was the construction of the KamAZ truck factory on the Kama River. This project involved a large consortium of Western companies, notably American and French (including Renault), and was financed in part by Western loans.

It is mainly used to transport heavy loads and as a base for weapon launch systems.”

This case perfectly illustrates the ambiguity of transfers, as KamAZ trucks, although designed for civilian use, quickly became the basic platform for many Soviet weapons systems, including mobile rocket launchers. In the field of information technology, despite strict controls, sales were made by Western companies, while the USSR lagged behind technologically by at least five years, a gap that continued to widen.

The development of Western-financed economic exchanges was a godsend for Kremlin leaders, as it relieved them of concerns about domestic supply and gave them the means to focus on strengthening their military potential. The concentration of resources in the militaro-industrial complex enabled the USSR to achieve “quasi parity” with the United States in many areas of armament (ballistic missiles, combat aviation, nuclear submarines). Thus, East-West trade indirectly subsidized a colossal Soviet military effort that the country’s economy, left to its own devices, could not have sustained. We are paying the price for this now, as Putin is ravaging Ukraine with the weapons stockpiled during those years.

But East-West trade had other advantages in the eyes of the Kremlin leaders. It undermined Western solidarity. Under pressure from Europeans eager to secure contracts in the USSR, the lists of COCOM, the body responsible since 1950 for compiling an inventory of so-called “strategic” products and technologies whose export to the Communist bloc was prohibited or subject to strict authorization, were relaxed. The embargo system was leaking from all sides, sparking acrimonious transatlantic quarrels, much to the delight of the Kremlin.

In the early 1980s, the Siberia-Europe gas pipeline was the subject of a major political and economic confrontation within the Western alliance, pitting the United States against its European allies in spectacular fashion. For the Soviet Union, the stakes were enormous: the pipeline was to provide it with a stable and massive source of hard currency, essential for financing its imports of grain and technology and for supporting an economy that was running out of steam. In the long term, Europe’s dependence on Russian gas would inevitably lead to a shift into the Kremlin’s orbit, it was hoped in Moscow. Western European countries, particularly West Germany, France, and Italy, convinced that economic interdependence would make war “materially impossible,” found it difficult to resist the economic incentives, as the project represented billions of dollars in contracts for their high-tech industries (gas turbines, compressor stations, and special steel pipes). Faced with a united European front, the Reagan administration was forced to back down. In 1982, it announced the lifting of sanctions introduced after the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan.

For those who had imagined that East-West trade would be a new Klondike, the awakening was brutal. Western investors were confronted with the lack of financial discipline of Soviet companies, accustomed to being bailed out by the state, late payments, and unilateral renegotiation of contracts. This cast doubt on the “convergence theory” that was so popular in the West. It became clear that, as always, the Russian autocracy was seeking to absorb Western technology without adopting the liberal institutions on which the market economy is based.

The crisis came to a head in March 1981, when Poland declared itself unable to repay its debt and asked its Western creditors for a moratorium. It was followed by Romania in June 1982, then by Hungary and Yugoslavia, which came close to bankruptcy. Western banks, which had lent heavily, felt the shock. They realized that the debtor ultimately held the creditor hostage. At the same time, Westerners realized that the USSR had taken advantage of the détente to engage in large-scale espionage. On April 24, 1974, Günter Guillaume, one of Chancellor Willy Brandt’s closest associates, was exposed as a spy for the GDR. Institutions such as the Franco-Soviet Chamber of Commerce, which were supposed to promote trade, also served as channels of information and points of contact for economic intelligence operations.

Ultimately, the influx of Western credit and technology gave the communist regime a fifteen-year reprieve. When we think of the moral damage caused by the Brezhnev era, the development of cynicism, violence, and immorality that marked those years characterized by a frenzy of material acquisitions, we cannot help but think that it would have been better if the regime had collapsed a generation ago. Instead, it is rotting away to the point where the damage will be fatal by the time Soviet leaders decided to try to remedy it.

The “reset,” that is, deliberately forgetting the hard-won experience of the past, seems to be the rule in relations between Russia and Western countries.

No sooner had Gorbachev pretended to introduce “socialism with a human face” than there was another rush: this time, people proclaimed, “we must help Gorbachev.” As a result, on December 4, 1991, the USSR suspended payment of its $70 billion debt. Europe bore more than 75% of this debt, or more than $52.5 billion. Germany bore 36%, France 10% ($41.3 billion), Italy 7%, Great Britain 5%, Japan 2.5%, and the United States 1.25%. By December 1, 1991, at least $25 billion had been taken out of the USSR through clandestine channels. Once again, French taxpayers footed the bill: they payed more than half of France’s claims on the USSR, or more than 20 billion francs, 1,379 per taxpayer per year.

Thus, the West kept the Soviet economy afloat throughout the communist period. Today, Russian leaders speak nostalgically of the lend-lease granted to the USSR by Roosevelt during World War II, which made it possible to feed the Soviets, strengthen their military capabilities, and ultimately establish Stalin’s control over half of Europe.

This is essentially the model being proposed to the Trump administration: the Kremlin has understood that without U.S. support, Russian hegemony over the entire European continent is impossible. What is new is that the U.S. now seems to share Russia’s view of the economy as an instrument for dominating the weak.

The nature of the projects discussed with Witkoff unquestionably outlines a plan for a Russian-American condominium over Europe.

Françoise Thom

[01] It should be noted that the Soviets would resume this practice. Litvinov wrote to Stalin on March 31, 1937: “The possibilities [of influencing public opinion] are particularly great in France. There, it is possible to gain influence over all newspapers, even those as hostile to us as Le Matin. The only problem is money.” See Sabine Dullin, Des hommes d’influence, Payot 2001, p. 21

[02] The porters’ associations fought a long and futile battle to obtain compensation. It was not until 1997, nearly 80 years later, that an agreement was signed between Paris and Moscow, providing for largely symbolic compensation covering only a tiny fraction of the sums lost. Moscow was then in dire straits and in urgent need of new foreign financing.

[03] Quoted in: Michael Hopkins (ed.), Cold War Britain, 1945-1964, Palgrave 2003, p. 11.

[04] Cable dated May 13, 1918. Quoted in: Zbyněk Anthony Bohuslav Zeman (ed.), Germany and the Revolution in Russia, 1915-1918, Oxford University Press, 1958, p. 124.

[05] Quoted in: Joseph Noulens, Mon ambassade en Russie soviétique, Plon 1933, vol. 2, p. 53.

[06] Quoted in: Joseph Noulens, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 59.

[07] Louis de Robien, Journal d’un diplomate en Russie, Vuibert, 2017, p. 308.

[08] Quoted in: Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution, Vintage Books NY, 1991, p. 623.

[09] Quoted in: I.I. Minc (ed.), Pobeda sovetskoï vlasti v Zakavkazie, Tbilisi, 1971, p. 308.

[10] George A. Brinkley, Allied Intervention in South Russia, University of Notre Dame Press, 1966, p. 209.

[11] Quoted in: Edward Hallett Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 3, Penguin Books, 1984, p. 166.

[12] Martin Guilbert, Churchill, London, 1991, pp. 423-424.

[13] Quoted in: Edward Hallett Carr, op. cit., vol. 3, Penguin Books, 1984, p. 289.

[14] Quoted in: Edward Hallett Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 3, Penguin Books, 1984, p. 277.

[15] Edward Jay Epstein, The Secret History of Armand Hammer, Random House, 1996.

[16] Quoted in: G.M. Alexeev, “S.S. Khromov: Leonid Krasin,” Otetchestvennaïa Istoria, no. 1, 2003, p. 183.

[17] A. Kvachonkine (ed.), Bolchevistskoïe roukovodstvo. Perepiska 1912-1927, Moscow, 1996, p. 215.

[18] A. Kvachonkine, op.cit., p. 224.

[19] P. V. Makarenko, “Koursom Rapallo: SSSR i Guermania v 1922-1927 gg.,” Voprossy istorii, no. 10, October 2011, pp. 29-45.

[20] Quote from Louis Fischer, October 28, 1933, cf. Europe Nouvelle, no. 821, p. 1060.

[21] Quoted in: Sabine Dullin, Des hommes d’influence, Payot, 2001, p. 33..

[22] S. Dullin, op. cit., p. 199.

[23] Robert Coulondre, De Staline à Hitler, Perrin, 2021, p. 54.

[24] L. A. Bezymenski, « Sovetsko-guermanskie dogovory 1939

See Also:

- « Les échanges économiques, une arme méconnue dans la guerre hybride du Kremlin contre l’Occident (1) L’empreinte léninienne » — (2025-0907) —

- „Wirtschaftsbeziehungen als verkannte Waffe im hybriden Krieg des Kremls gegen den Westen (1) Das leninistische Erbe“ in Desk Russie — (2025-0907) —

- « Economic Relations, an Underestimated Weapon in the Kremlin’s Hybrid War against the West – I. The Leninist Imprint » in Desk Russia — (2025-0911) —

In-depth Analysis:

The appeal of the Russian market, perceived as an El Dorado by Westerners, stems from a historical strategic blindness. For centuries, the West has deluded itself into believing that trade can integrate Russia as a rational and peaceful player in the global economy.

However, this vision is fundamentally flawed. For the Kremlin, from the Tsarist era to the present day, trade is not an end in itself, but a pure instrument of power. It is a means of acquiring technology and capital to strengthen its military apparatus and consolidate its regime, while weakening its adversaries.

As historian Françoise Thom demonstrates, Russia tirelessly repeats a “cycle of predation”: it attracts foreign investors to modernize, then plunders or expels them once its objectives have been achieved.

The West, confusing its own hopes with Russian reality, has thus continually financed its own adversary. It has never understood the Kremlin’s strategy of disguising its quest for power as economic cooperation. Lenin cynically summed it up: “The capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.”

- « Economic Relations, an Underestimated Weapon in the Kremlin’s Hybrid War against the West – I. The Leninist Imprint » in Desk Russia — (2025-0911) —

- « Les échanges économiques, une arme méconnue dans la guerre hybride du Kremlin contre l’Occident (1) L’empreinte léninienne » in Desk Russia — (2025-0907) —

- „Wirtschaftsbeziehungen als verkannte Waffe im hybriden Krieg des Kremls gegen den Westen (1) Das leninistische Erbe“ — (2025-0907) —

- ‘Cesspool and chaos: the Russian connection in the Epstein Affair’ in Desk Russia — (2025-0730)

- « Le cloaque et le chaos : la Russian connexion de l’affaire Epstein » in Desk Russie — (2025-0728) —

- „Die Kloake und das Chaos: Die russische Verbindung der Epstein-Affäre“ — (2025-0728) —

- « Клоака і хаос: російський зв’язок у справі Епштейна » — (2025-0728) —

- « La paille et la poutre : une réponse européenne aux idéologues trumpo-poutiniens » in Desk Russie — (2025-0708) —

- « The Pot Calling the Kettle Black: A European Response to Trump and Putin Ideologues » in Desk Russia — (2025-0708) —

- « A Disaster of the First Magnitude » in Desk Russia — (2025-0706) —

- « Toward a Putin–Trump Pact? in Desk Russia — (2025-0430) —

- « Vers un pacte Poutine-Trump ?» in Desk Russie — (2025-0429) —

- « Toward a Putin–Trump Pact? » in Desk Russia — (2025-0430) —

- « Russia’s Plan for the United States » in Desk Russia — (2025-0413) —

- « Le projet russe pour les États-Unis » in Desk Russie — (2025-0329) —

- « Vladimir Putin’s Twofold Revenge » in Desk Russia — (2025-0304) —

- « La double vengeance de Vladimir Poutine » in Desk Russie — (2025-0303) —

- « The Lessons of Trumpism for Europeans: How to Avoid a ‘Self-Putinization’ of the EU » in Desk Russia — (2025-0225) —

- « Les leçons du trumpisme pour les Européens : comment éviter une autopoutinisation de l’UE » — in Desk Russie — (2025-0223) —

Desk Russie would like to remind you that Françoise Thom will be presenting a series of five lectures entitled ‘The Kremlin’s instruments and methods of power projection from Lenin to Putin’ as part of the Université Libre Alain Besançon. For more details and to register (in person)