François Guizot-Institut de France 2022 Award Ceremony — Monday 4 October 2022, 6:30 PM, Grande Salle des Séances — Speech by Patrice Gueniffey, vice-president of the jury — Sources: Institut de France & François Guizot Association —

Table of Contents

Mr. Chancellor of the Institute,

Mr. President of the Association François Guizot,

Ladies and Gentlemen members of the jury of the François Guizot-Institut de France Prize,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Françoise Thom,

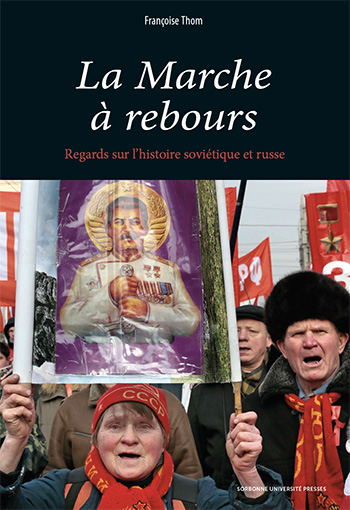

When I called you to tell you that the jury of the Prix Guizot/Institut de France had awarded your book, La Marche à rebours. Regards sur l’histoire soviétique et russe (The Backward March, a look at Soviet and Russian history), you told me – which honors your modesty – that you certainly owed this distinction to the current war between Russia and Ukraine.

It is probable that a more timid jury would have preferred to reward a work less linked to current events. But our jury has only weighed the merits of this book: on the one hand, it wanted to show its admiration for this wide and fascinating journey through Russian history from the Old Regime to the post-Soviet era; on the other hand, it wanted to honor several decades of research, of which this book represents the achievement. You have many titles to the esteem, and even more, of your colleagues and of those who read you.

You came to history, not by training or by vocation, but to find answers to the questions raised by your long stay in Brezhnev Russia.

You belong to the happy few who never succumbed to the seduction of revolutionary ideas

There is something singular in your intellectual biography. You are one of those people in your generation, which is also mine, who never succumbed to the seduction of revolutionary ideas.

In the early 1970s, however, the revolution remained a hope for many young people, and even after your return in 1978, it still had supporters. It was still very present in political, intellectual and academic life. Of course, The Gulag Archipelago had been published in France in 1974.

Despite this, some people were still enthusiastic about the « liberation » of Phnom Penh and communism was trying to find a second wind with the lies of « Eurocommunism » or « socialism with a human face ».

The ideological passions of your time had no effect on you. Did you owe this immunity to the fact that you had received an education faithful to the old tradition of the humanities? To the fact that you had gone to Russia because you liked its language, its literary culture and its poets?

In the chapter of your book that deals with the first steps of Soviet diplomacy, you quote these words from a witness about Jacques Sadoul, whom the Bolsheviks recruited shortly after the October Revolution: « He had a very sincere admiration for the leaders of Bolshevism. This inclination made him very predisposed to be a dupe. He had absolutely no knowledge of the Russian language and was therefore deprived of all those means of control and comparison which numerous private conversations provide. »

In the archives of the satellite countries

Not only did you yourself have no admiration for this ideology and its defenders, but you also had a command of the Russian language, which put you far above the revolutionary youth of the West, who did not understand Russian any more than they understood Albanian or Chinese. I am thinking, in evoking your itinerary, of Simon Leys, whose knowledge of Chinese prevented him from being trapped in Maoism.

Without the meeting with Alain Besançon, who became your mentor and your thesis director, and whose work has accompanied you ever since, perhaps you would not have chosen to become a historian. Alain Besançon had the wisdom to introduce you to the study of history through a theme that related to language and the uses of discourse, in short to literature, even if it had been misused, since you devoted your doctoral work to La Langue de bois (The language of wood), which was published by Julliard in 1987.

The intellectual climate had changed a lot by then – I’m talking about France -: between the beginning of the 1980s and the middle of the 1990s, there was a small liberal window that soon closed again. The Democratic Regain, as Jean-François Revel used to say.

Alain Besançon — Photo La règle du jeu

It did not last. But during these years totalitarianism was at the heart of a vast reflection. An insufficient reflection, no doubt, since it looked back without seeing – but could one then? – the new totalitarianism that was rising like a bad dough: the civilizational war after the collapse of universalist ideologies. The fall of the USSR allowed the opening of the archives for a few years, not much more. You told me that access to them was in fact subject to the payment of bribes that exceeded your possibilities. So, while American historians and students went to the Moscow archives to stock up on photocopies, you took a detour to the periphery, exploring the archives in Georgia, the Baltic States and various republics of the former USSR. Good for you, because your harvest was rich: it is it that fed the writing of your very great book on Beria, the Janus of the Kremlin, published in 2013. A new book, first of all, on the mysteries of the Kremlin and the power struggles that followed Stalin’s death; a new portrait of the character, secondly, too often reduced to an incarnation of ideological fanaticism or to the pathologies that were attributed to him; a model of biography, finally, holding from beginning to end the balance between what the biographer can support with evidence and what, by force of circumstance, he is forced to imagine.

The great coherence of your work

Your deep knowledge of Soviet political mores protected you from risky hypotheses, and from that propensity, quite common among historians, to confer on their « hero » not only more importance than he has, but to lend him convictions or ideas even when he lacks them: your Beria, cynical, calculating, clever, is furiously reminiscent of Fouché.

This Beria, neither psychopath nor fanatical ideologue, is all the more disturbing.

In La Marche à rebours, there is a portrait of Nicolaï Ejov which, added to your monumental Beria, could form the beginning of a kind of revolutionary teratology, a bit like the one Taine had sketched when he placed side by side the three revolutionary psychological types: the madman, the buccaneer and the cuistre.

Françoise Thom — Photo Institut de France

What stands out in a continuous reading of your book is the great coherence of your work, because at no time does one have the feeling of reading a collection of essays, but a reflection on the history of the USSR in which the fate of the former republics plays a large part.

The Ukrainian War

The current war has at least one merit: it reminds us of the existence of what was once called geography. It is certain that 99% of our contemporaries would be unable to locate Georgia or Armenia on a map. Now, the percentage has certainly dropped a little when it comes to Ukraine: not too much, though, because the fate of Ukraine is of interest to the West only insofar as its possible repercussions on our living conditions.

Nevertheless, the images of tanks, bombed buildings and trenches, so strange, so anachronistic after 70 years of peace – the war in the former Yugoslavia took place in general indifference – remind us confusedly of the tragic history which was that of these « lands of blood » (to use the title of the great book by Timothy Snyder). We sense that what is happening there is part of a history in which the same things have happened before. One element, however, is missing in the perception of the events and in their analysis: communism.

It is precisely the great merit of your book to reintroduce into this history, which is tragic from start to finish, a regime, an ideology, a history without which we would not understand, but which seems to have disappeared as surely as Atlantis.

The disappearance of communism It is certainly one of the great enigmas of the end of the 20th century

It is certainly one of the great enigmas of the end of the 20th century that the disappearance of communism. The great passion of the last century has suddenly disappeared. The amnesia was total, immediate, irreversible. Between Hitler and Stalin, memory has chosen. For the younger generations, communism is as evocative as the Hundred Years’ War. Dissident writers who played a decisive role in delegitimizing communist ideology and regimes have fallen into a memorial abyss. Even Solzhenitsyn, whose Gulag Archipelago no French publisher considers it worthwhile to reissue, not to mention the cycle of The Red Wheel. Where have they gone?

That Putin’s Russia does not honor them is fine, but the West itself has forgotten them. Could it be because their anti-communism did not make them admirers of Western societies?

I do not believe that, in history, one can find another case of abolition of memory as complete and irreversible as that to which communism has been subjected. Its principles, its references, its ideals, its conception of history, its crimes, everything has disappeared. What was once the youth of the world has gone straight to senility.

The revolution continues to have followers, and many of them, especially in France, but they no longer share either the belief in the creative power of history or the universalism of the philosophies of the revolution. Wokism is certainly revolutionary, but it has no link with the revolutionary culture that was the culture of the West for two centuries: revolution without history, revolution reduced to the individual or to the community of race or gender.

How to understand post-Soviet Russia

Writing the history of communism today, Soviet or not, is like making the history of Hellenistic royalty. And yet! How to understand post-Soviet Russia, after the Yeltsin years, without starting from the Soviet experience? Even if ideology has disappeared, including in Russia, the USSR continues in a certain way: today’s Russia is the daughter of the fall of the USSR in 1991 and of the Yeltsinian chaos to which you devote a long and fascinating analysis. Ideology is dead, but it has shaped so many minds, it has inculcated so many reflexes and representations that it remains alive. In this too, your work is precious, and for another reason: it reminds us how much ideologies, whatever they are, are deadly.

Now, if there is little chance of seeing communism rise from its ashes, other totalitarian ideologies threaten us: neofeminism, apocalyptic ecology, Islam. And in a world populated by disarmed souls, to use Allan Bloom’s word, in a world where the chain of transmission has been broken, ideologies have, I believe, a bright future ahead.

Eternal Russia: Forever the same ?

The conclusion of your book brings Russia, the Russia of old, back into the debate. You know, of course, that General de Gaulle refused to speak of « Soviets », believing that these so-called Soviets were only the temporary face of a Russia that remained itself through the vicissitudes of history, and forever separated from the West.

You seem to believe that the fall of Putin could open a new chapter in Russian history, or even allow it to experience more liberal political conditions. Can we really hope for a different future for the Russian people?

In my opinion, the great interest of your book lies precisely in the links you weave between the Russia of before, the Russia of always, and the Russia of after: it is the same one, whose genius is purely « oriental » in spite of the puffs of the West that sometimes take hold of this country-continent with uncertain borders. The Italian ramparts of the Kremlin and the facades of the buildings of Saint Petersburg are decoys. A liquid empire, said Michelet, moving like the Rus which, moving from Kiev to Novgorod and then to Moscow, finally chose a destiny where the memory of the Golden Horde prevails over the Hanseatic League that could have become a Russia constituted around the merchants of Novgorod.

The fate of Russia has been sealed for a long time. Until today, Ivan the Terrible and the opritchnina continue to rule Russia.

Is democracy a Western privilege ?

We must agree: democracy is a Western privilege. From this point of view, Russia is not an anomaly in a world dedicated to freedom: on the contrary, like so many other countries, it bears witness to the privilege that is ours, the fruit of a thousand-year-old history that has always been ordered to freedom. You do not hide behind the so-called scientific neutrality of the historian. You take sides. One understands ery quickly, while reading you, that you are not a friend of the Russian ogre, and that on the contrary the small peoples who have the misfortune to live on its borders are entitled to your committed sympathy.

Some of your readers, however, will not be able to resist thinking that you sometimes force the line a little, that you are too closely attached to that tradition hostile to Russia which goes back to the letters of Custine and which finds its counterpart in a « russophile » party as excessive in its judgments as its antagonist is. History, as you know, is not written in black and white. Our era has an unfortunate tendency to confuse history with morality. History is a gray area where good and evil are not always, or even often, easy to distinguish.

This is a minor disagreement, dear Françoise. It does not detract from the admiration that your work arouses, carried by an iron conviction and a science rarely equaled.

Patrice Gueniffey

- Discours de Xavier Darcos, chancelier de l‘Institut de France — (2022-10-04) —

- « Prix Guizot -Institut de France 2022 : And the Winner is… Françoise Thom » : Allocution de Stéphane Coste, descendant de François Guizot et président de l’association François Guizot — (2022-10-04) — English pdf version of Stephane Coste’s speech — « The François Guizot-Institut de France Prize 2022 » — (2022-10-04) —

- « La Russie d’avant, la Russie d’après, c’est la Russie de toujours » — Discours de Patrice Gueniffey & « Russia, Forever the Same ? » — Speech by Patrice Gueniffey, vie-president of the jury — (2022-10-04) —

- « Westerners Have Great Difficulty in Perceiving the Reality of the Totalitarian World » : Speech by Françoise Thom, winner of the Prix François Guizot-Institut de France 2022 — & « La Russie d’avant, la Russie d’après, c’est la Russie de toujours » — (2022-10-04) —

- « Russie : Pouvoir autocratique et logique léniniste: Qui va éliminer l’autre ? » — Réponse de Françoise Thom, lauréate du Prix Guizot-Institut de France — « Westerners Have Great Difficulty in Perceiving the Reality of the Totalitarian World » — Speech by Françoise Thom after she was granted the Guizot Price — (2022-10-04) —

- Voir également : « Françoise Thom, La marche à rebours. Regards sur l’histoire soviétique et russe » par Andreï Kozovoï in Cahiers du Monde Russe 63/3-4 | 2022, 863-866 — (2022-1202) —