In the smoking crater of Berlin, amidst the ruins of the vanquished Reich, French gendarmes follow in the footsteps of the occupying troops. Stationed at Camp Foch, they are first a force tasked with carving order out of chaos. But as an “Iron Curtain” descends across the continent, their mission shifts dramatically.

It all begins in the apocalypse of 1945. Sent to impose order on the fallen capital of the Reich, they take up quarters amidst the rubble. But history grants them no respite. As the Cold War splits the world in two, their role is transformed in the heart of the European powder keg. For nearly fifty years, their destiny and Berlin’s would be one and the same.

They would be on the front lines during the two major crises that forged the city’s legend: the Blockade of 1948, which they endured with the help of the airlift, and the construction of the Wall in 1961, where they became guardians of the free side. Day after day, they helped preserve this island of democracy in the face of totalitarianism.

The fall of the Wall in 1989 was not the end of their mission, but its triumph. Their departure in 1994 closed a unique chapter: that of victors who, in half a century, accompanied Berlin on the long road to freedom and its full sovereignty.

The departure of the last gendarmes in 1994 signals not just the end of a story, but the end of a metamorphosis: that of men who arrived as conquerors, became the guardians of a free city, and left as guests on soil that had finally regained its sovereignty.

First occupiers, then protectors. Finally, guests. Such is the incredible odyssey of the French police in Berlin. Editor’s note

Table of Contents

By Benoît Haberbush (*) — Melun, 8 October 8, 2025 — (Transcript of a lecture at the Allied Museum in Berlin)

At the end of the Second World War, the French Gendarmerie sent men to follow the French soldiers who had come to occupy a part of Berlin, the former Nazi capital. Amidst these ruins, the gendarmes witnessed the rise of a city with a unique status against the backdrop of the Cold War. These soldiers linked their fate to this city for nearly half a century.

I- Establishment and Changes of the Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment

In July 1945, the first French elements arrived in Berlin and settled in the districts of Wedding and Reinickendorf, which had been conceded by the Soviets. Throughout the period, the gendarmerie forces were composed of gendarmes and republican guards.[01] The Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment (D.G.B.) was initially administered by the 1st Gendarmerie Legion of Neustadt in West Germany, before gaining its administrative autonomy on July 1, 1946. The unit partially set up in wooden barracks that had belonged to the Luftwaffe. The base was named Camp Foch.

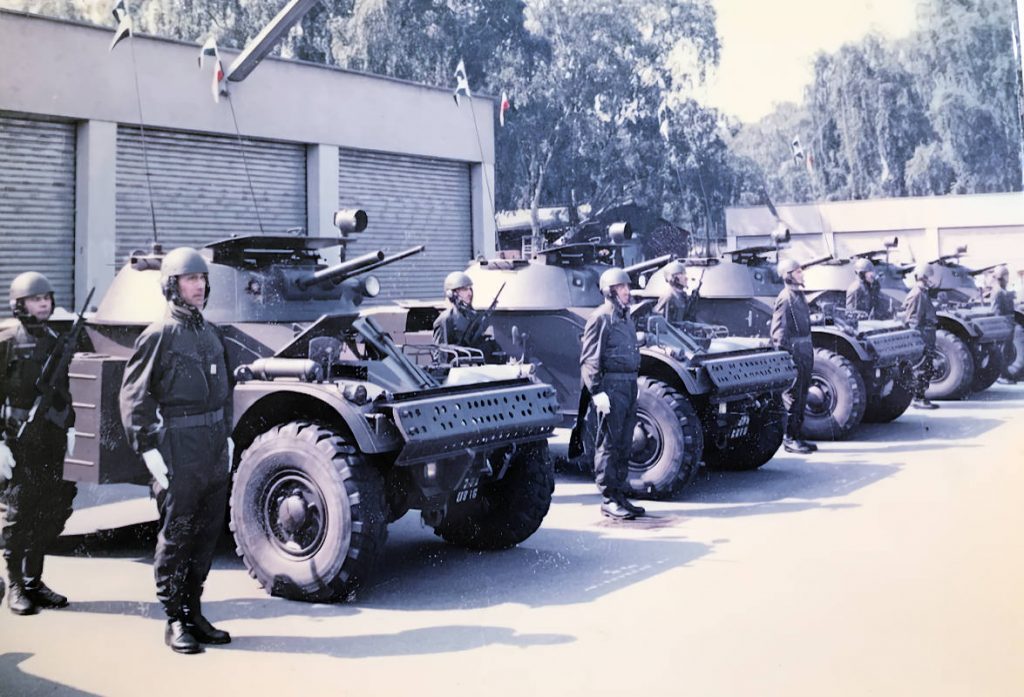

The D.G.B. consisted of a headquarters staff, a departmental gendarmerie section (with three territorial brigades in Frohnau, Wedding, and Reinickendorf, and a reserve brigade in Wedding), a security squadron, and the 13th mobile squadron. The early days were difficult in this city in ruins. Everything was lacking. The few vehicles provided were insufficient and worn out. The weaponry was not suitable for service.

Just as the setup phase was barely completed, the international context weighed on the detachment’s organization. On one hand, problems posed by settlers in French possessions led to regular withdrawals of personnel. These departures, for varying lengths of time, disrupted service by disorganizing units and depriving them of their specialists (drivers, radio operators, etc.). Fourteen non-commissioned officers were killed in Indochina, and one officer died in French North Africa in 1961.[02]

On the other hand, threats related to the Cold War led to several adjustments. Having become the true barometer of East-West relations, Berlin became a focal point for tensions with every new event. The 1948-1949 blockade was a real shock for the gendarmes, who found themselves isolated from the “free world.”

This event had two major consequences. On May 1, 1948, a new squadron reinforced the D.G.B. Furthermore, the tremendous development of the Berlin-Tegel airport led to the creation of an air gendarmerie post attached to the 1st Air Division of Lahr in West Germany.[03] At the end of 1948, the detachment included a headquarters staff, a gendarmerie section (three brigades, a reserve brigade, and a research file), mobile squadron No. 9, two security squadrons (one of which was dissolved in 1949), based at the Napoleon barracks, and a maritime brigade at Tegel (abolished in 1949).

Subsequently, the two squadrons changed their designations several times.[04] In July 1952, the gendarmerie section was eliminated. It was replaced by a motorized military police platoon, created in each security squadron. It was first called the “judicial police group” in July 1962, then the “provost company” in November 1967. The detachment’s non-commissioned officer strength decreased from 535 to 360. The construction of the Berlin Wall did not lead to any significant organizational changes.

However, a major restructuring occurred following the events of May 1968. September 30 marked the dissolution of the Berlin detachment as a corps. It became a simple command echelon. Security squadron No. 2, formed into a provisional squadron, was sent to mainland France to reinforce public order units. The reduction in force also affected the provost company. To compensate for this departure, a company of gendarme cadets was created at the Napoleon barracks. This school provided the same training as in mainland France but had its own unique characteristics that made it distinctive.

It was an operational combat unit integrated into the French military security apparatus. The cadets trained in the sandy basin of Heiligensee and participated in tripartite maneuvers.[05]

They also performed auxiliary duties at the Allied Kommandatura[06] and Spandau Prison. Finally, the school served as a showcase for the Gendarmerie. Many trainees distinguished themselves in military sports competitions.

In the two decades that followed, the force remained under 300 officers, non-commissioned officers, gendarmes, and cadets. The fall of the Berlin Wall and German reunification precipitated the departure of French military personnel and, therefore, the gendarmes. The German authorities were all the more impatient as they were financing the maintenance of the French units. On September 1, 1991, the D.G.B. was reduced to just 15 officers, NCOs, and gendarmes. The gendarme-cadet company was dissolved. By 1994, there were no more gendarmes in Berlin (except at the embassy).

II- Permanent Missions

The basic missions of the D.G.B. were quickly defined. Several of them remained valid until 1989. As early as January 21, 1946, an instruction set the conditions for the employment of the departmental gendarmerie and the republican guard. Lieutenant-Colonel Guin, commander of the D.G.B. from 1951 to 1956, perfectly summarized its scope of action: “Faithful to the principles dictated to it by Article 1 of the Decree of May 20, 1903, on the service of the Gendarmerie, the Gendarmerie of Berlin ensures public safety and maintains order and the execution of the laws. It thus remains an essentially protective force for order, the security of the French people, and their property.”[07]

First, the departmental gendarmes had the same responsibilities as in France, providing judicial, administrative, and military police services for the French sector of Berlin. The very particular status of the city, however, required some adaptations. At the judicial level, their jurisdiction extended to compatriots present in Berlin, to Germans involved in cases concerning French nationals, and to British, American, or Russian nationals present in their sector.

At the French tribunal, the gendarmes provided court services and prisoner transfers. Furthermore, they informed their country’s military authorities of all events that could affect the security of the French in Berlin. They cooperated with public security, military security, special services, and, where appropriate, with the German police. Finally, the gendarmes provided military police services to French soldiers stationed in Berlin and to visiting Allied military personnel.

The mobile gendarmerie squadrons were more specifically tasked with public order and security missions. Certain tasks were permanent, such as the protection of French or Allied installations (the Napoleon barracks, the political division building, the general’s office, Tegel Airport, the Allied Kommandatura, etc.), traffic control in the Napoleon district, or the control of access routes to the French sector by road (Babelsberg or Helmstedt checkpoints) or by rail.

The great originality of these units was to be completely integrated into the defense system of the French sector.

This situation resulted in enhanced military training, continuous reconnaissance at the edge of the French sector, and periodic exercises. These men were called upon to provide pickets and intervention units as a first response in case of public disturbances, strikes, or riots.

At the same time, the security squadrons carried out semi-permanent tasks. From 1947 to 1987, they provided personnel to guard Spandau Prison for three months of the year. Eight Nazi war criminals were initially detained there. Then, through releases, Rudolf Hess became the sole prisoner until his death in 1987. Each changing of the guard with the Allies was marked by a formal ceremony.

Likewise, the mobile gendarmes participated in the reinforced security of the Napoleon barracks or in road safety presentations given for the benefit of the troops. In terms of military training, the mobile gendarmes took part in numerous exercises and maneuvers organized in collaboration with the French army, the Allies, or the German police. Their names, such as Catch-all or Straight-flush, were a program in themselves.

In addition, there were more occasional tasks. The arrival of high-ranking personalities mobilized part of the personnel (motorcycle escort, honor guard). Mobile gendarmes also guarded the embassy during each stay of the French ambassador or the general commanding the French forces in Germany (C.C.F.A.). Furthermore, sports championships occasionally mobilized personnel (participants, referees, timekeepers, controllers, secretaries, etc.).

III- The Evolution of Missions: From Occupation to Protection

While the basic missions of the D.G.B. hardly evolved over 50 years, its role changed significantly due to the context. In 1945, this unit was primarily an occupation force charged with imposing the victors’ terms on a defeated nation. The French were particularly receptive to this issue as their own country had been occupied. The gendarmes were especially tasked with discovering weapons still hidden in some factories. They also participated in the denazification of German society by tracking down war criminals and monitoring the formation of secret organizations like “Edelweiss,” for example. The large movements of populations of different nationalities (prisoners, forced laborers, deportees) complicated the task of the law enforcement officers. Furthermore, the extreme precariousness in which Berliners lived, holed up in the city’s rubble, fostered all kinds of trafficking. Lieutenant-Colonel Hurtrel wrote in September 1946: “Class differences have disappeared in the misery. (…) The only wealthy people today are the black market traffickers, whose suppression is underway but will only fully succeed when goods in increased quantity and everyday items appear on the market.”[08]

In 1994, the gendarmes would have been better off taking these magnificent mosaics, created by gendarmes during their assignment in Berlin, back to Melun. After months of dilapidation of the commissaries and finally a reconstruction project, the developer could have at least donated them to the Allied Museum in Berlin. Editor’s Note

The Cold War radically changed the situation. The blockade imposed by the Soviets led to an initial awakening. In addition to combating trafficking, the gendarmes received other instructions that reflected new concerns. For instance, in December 1948, the gendarmerie brigades were instructed to prohibit the sale of Soviet-licensed newspapers. The same month, strict measures were taken for the elections organized in West Berlin. All detachment personnel were confined to quarters starting December 1st. Numerous patrols were organized. The gendarmes provided surveillance of polling stations and set up filtering checkpoints.[09] In 1949, the gendarmes’ families were even evacuated. They only returned gradually.

The defense plans developed at that time testify to the concerns of the moment. In February 1953, for example, one of them entrusted the gendarmes with the task of protecting the assembly of Allied nationals stationed in the French sector at Camp Napoleon, as well as reconnoitering and slowing down the enemy’s advance for as long as possible by carrying out necessary demolitions.[10]

Intelligence became a priority. Gendarmerie reports accounted for information gathered in the Western and Eastern zones (refugees, strikes, etc.). Patrols on the edge of the French sector multiplied. To avoid any misstep in this explosive context, the gendarmes received strict instructions: “at no time and under no circumstances will fire be opened as long as the Allied Forces have not themselves been fired upon by the Soviets.”[11]

In August 1961, the construction of the Berlin Wall suddenly increased tensions. On August 14, the soldiers of the detachment were confined to their quarters. Starting on the 16th, the security squadrons were on permanent alert at the Napoleon barracks. In the following days, the gendarmes reported numerous incursions of Soviet vehicles into the French zone and attempts to encroach on the French zonal boundary with the wall. The patrols sent along the wall multiplied to display the resolve of the Western powers. The permanent nature of the wall led to an increase in tasks for the gendarmes (sector patrols, operational alert, checks at Checkpoint Charlie, etc.).

BC Benoît Haberbush — All rights reserved

After the 1968 reorganization, service normalized, and the detachment focused on its basic missions. Unlike the Allies, the gendarmes did not limit their activities to simple military police work. They retained broad judicial prerogatives. A certain cooperation developed over time with the Berlin police, even though the French community lived relatively withdrawn. During the 1970s and 1980s, tension remained linked to the international context. The fall of the Wall in 1989 was a complete surprise for the personnel, as confirmed by General Choquet, then a lieutenant colonel and deputy commander of the detachment.[12]

Conclusion

The Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment thus constitutes a unique episode in the history of the Gendarmerie. The generations of gendarmes who served there over half a century witnessed the strange destiny of this city, which became a stake for two great powers. But the most remarkable fact undoubtedly remains the evolution of this force, which went from the status of occupier to that of protector before ending as an invited force, from 1990 to 1994, on foreign territory that had once again become sovereign.

Benoît Haberbusch

(*) Doctor of History, Commandant Benoît Haberbusch is co-holder of the HiGeSeT chair and head of the Strategy and Research Department at the Research Center of the National Gendarmerie Officers’ School (CREOGN).

Notes

[01] Name given to mobile gendarmes from 1944 to 1954.

[02] On May 23, 1952, a memorial room was inaugurated by the Berlin Gendarmerie detachment in memory of its members who fell in overseas operational theaters. As of that date, 244 soldiers had been provided by the D.G.B.

[03] A first air gendarmerie post, created in 1945, was dissolved in 1948, after the Soviets broke off the quadripartite relations in Berlin. It was later re-established. From an initial 3 gendarmes, the number grew to 5 in 1949, then 14 after 1975.

[04] At the beginning of 1949, security squadron No. 1 became security squadron No. 3, while mobile squadron No. 9 became security squadron No. 4. In November 1951, security squadron No. 4 changed its number again, becoming No. 2. In July 1952, it was the turn of security squadron No. 3, which became No. 1.

[05] Almost all were former drafted or enlisted non-commissioned officers.

[06] Created in 1945, the Kommandantura was an executive body for legislation enacted by the four occupying nations. The United States, Great Britain, the U.S.S.R., and France each had a permanent representative. The Soviets withdrew after 1948.

[07] Organization and service of the Berlin Gendarmerie detachment No. 50/4, Lieutenant-Colonel Guin commanding the D.G.B., S.P. 50.448, March 8, 1955, SHGN: detachment of the Berlin Gendarmerie, R/4, 1954-1956.

[08] Report No. 319/4 from Squadron Leader Hurtrel commanding the D.G.B. to the General Superior Commander of the French zone of Berlin, Berlin, September 23, 1946, SHGN: D.G.B., R/2, 1970 and R/4, 1945-1946.

[09] Order of employment No. 682/4 of the detachment for the maintenance of order for December 5, 1948, and the following days from Lieutenant-Colonel Hurtrel commanding the D.G.B., S.P. 50.448, December 2, 1948, S.H.G.N.: D.G.B., R/4, 1948-1949.

[10] Defense order No. 41/4, sub-group No. 3, Lieutenant-Colonel Hurtel commanding the D.G.B., S.P. 50.448, February 26, 1953, S.H.G.N.: FFA, D.G.B., R/4, 1948-1949.

[11] Letter No. 120/4 from Lieutenant-Colonel Hurtrel commanding the D.G.B., S.P. 50.448, July 1, 1953, S.H.G.N.: FFA, D.G.B., R/4, 1948-1949.

[12] Interview with General Choquet, Maisons-Alfort, June 3, 2002.

See Also:

- « Le détachement de gendarmerie de Berlin 1945-1994 (1) » — (2025-1008)

- « Das Gendarmeriekommando Berlin, 1945-1994 (1) » — (2025-1008)

- « The Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment 1945–1994 (1) » — (2025-1008)

- « Les képis de la guerre froide (2) » — (2025-1008)

- « Ein Képi über Berlin (2) » — (2025-1008)

- « A Kepi Over Berlin (2) » (2025-1008)

In-depth Analysis

French Gendarmes in West-Berlin : In 1945, French gendarmes entered a devastated Berlin, a landscape of ruins where everything was scarce. Their first mission was that of an occupying force: hunting down Nazis and combating the black market that thrived on misery.

With the 1948 Blockade, the Cold War froze the new reality in place. The gendarmes, isolated at the heart of the enclave, underwent a transformation. From occupiers, they became the protectors of the French sector.

Their days were defined by symbolic and tense missions. They stood guard over Spandau Prison, watching over the last Nazi war criminals, including the infamous Rudolf Hess.

Then, in 1961, the Wall went up—a concrete scar splitting the city in two. They were placed on permanent alert. Their patrols ran along this symbol of oppression, their eyes turned eastward, ready for anything. They were no longer just gendarmes, but soldiers on the front lines of the Allied defense.

The fall of the Wall in 1989 signaled the end of their historic mission. After standing with the city for nearly half a century, the last gendarmes left Berlin in 1994.

From victors to guardians, they had been the silent witnesses and key players in Berlin’s journey from darkness to freedom.