From occupiers to protectors, the French Forces in Berlin (FFB) radically changed the game. Initially sidelined after the war, France carved out its own sector to become a key player.

More than just soldiers, they were builders and agents of denazification. Then came the 1948 Soviet blockade, their moment of truth. While the United States and Great Britain dominated the skies, France played its hand on the ground. Their masterstroke: building an entire airport, Tegel, in a record 90 days.

Table of Contents

by Joël-François Dumont — Berlin, September 28, 2025

This was no mere construction project; it was a stroke of strategic genius. Tegel broke the Soviet stranglehold and ensured the success of the airlift. « It was the first time that air power alone would win a conflict. » This airlift became a legendary symbol of French determination and ingenuity. For nearly 50 years, their role far exceeded that of a simple garrison. They were spies, diplomats, and essential partners in the hottest hotspot of the Cold War. They turned former enemies into steadfast allies. The French didn’t just occupy Berlin; they helped save the city and guarantee its freedom.

The London, Potsdam, and Berlin Agreements

The history of the occupation of Germany and Berlin after 1945 is complex. Numerous negotiations and decisions spanned several months, and several major conferences were held. It’s no surprise, then, that one might confuse the different stages that led to the division of Berlin into four sectors. Curiously, the role of the French Forces in Germany (FFA) is better known than that of the French Forces in Berlin (FFB) between their arrival in 1945 and their departure in 1994. This is all the more reason to recall some memories and highlight a beautiful chapter of our contemporary history—a chapter that closed on September 28, 1994, with the departure of the French troops stationed in Berlin!

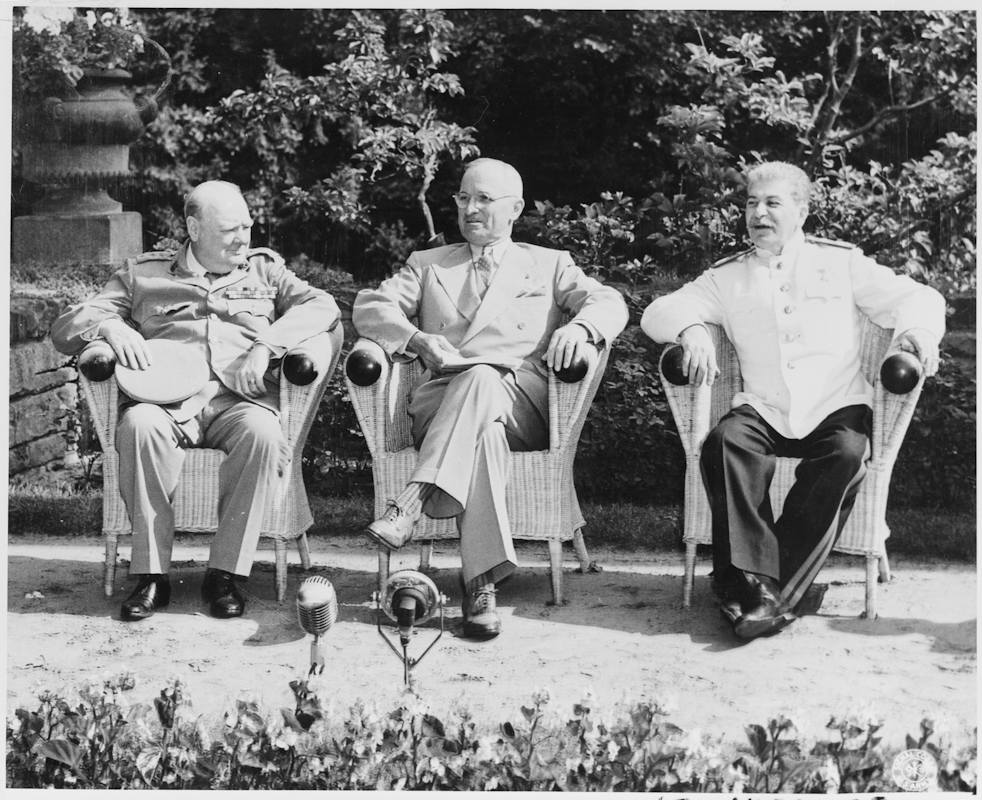

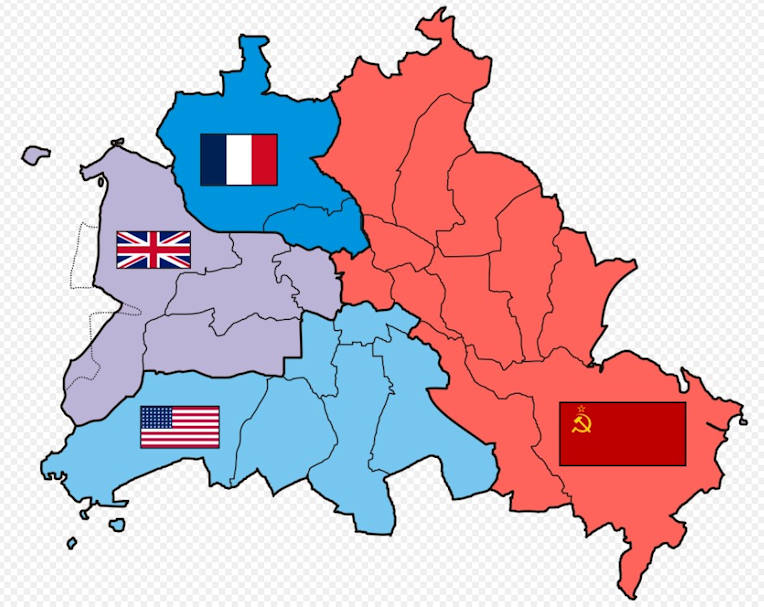

During the London Agreements in September 1944, the Allies had agreed with the Soviets to divide Germany after the Second World War: the eastern part would be under Russian occupation (GFSA), and the western part under American, British, and French occupation. The former capital of the Reich, Berlin, was divided later during the Potsdam Conference (July-August 1945) into three sectors: Soviet in the east, and American and British in the west.

The « Big Three » (Stalin, Truman, Attlee) made this decision without France, which was not invited to the conference. While France’s initial exclusion from Berlin seemed consistent with its absence from negotiations on the city’s status, it did not account for the reaction of General de Gaulle…

France had little to expect from Roosevelt. The General turned to « the old lion, » Winston Churchill, who decided to cede two Berlin districts from the sector allocated to Great Britain at Potsdam. Fortunately, Harry S. Truman had succeeded Roosevelt.

After the experiences of Tehran and Yalta, a wary Churchill, mistrustful of Roosevelt’s high esteem for Stalin, preferred to have France on his side (One never knows)… This is reminiscent of certain analogies drawn between Roosevelt and Trump regarding the occupant of the Kremlin…

The French Arrival in Berlin (1945)

French forces arrived in Berlin on August 12, 1945, following complex diplomatic negotiations led by General de Gaulle for France to obtain an occupation zone in Germany. The French sector primarily included the districts of Reinickendorf and Wedding in the northwestern part of Berlin, officially assigned on February 9, 1945. The French sector covered approximately 88 square kilometers and initially housed nearly 500,000 German inhabitants, about a quarter of West Berlin’s population.

Administrative and Military Organization

This French sector was placed under the authority of General Pierre Koenig, commander-in-chief of the French forces in Germany from 1945 to 1949, a hero of Bir Hakeim and an emblematic figure of Free France. The French Forces in Berlin (FFB) were led on the ground by General de Beauchesne and were based at Camp Cyclop in the Reinickendorf district.

The French establishment faced considerable challenges: Berlin was 75% destroyed, its infrastructure was in ruins, and the German civilian population lived in precarious conditions. The French forces had to manage the humanitarian crisis while maintaining order and implementing denazification directives.

On General Koenig’s proposal, General de Gaulle appointed General Jean Ganeval to Berlin, another iconic figure who would leave his mark on West Berlin more than any other as commander of the French sector.

It is worth remembering that in Berlin, the four Allied commanders were, in East Berlin, the Soviet ambassador posted in East Berlin, and in the Western sector, the ambassadors of the United States of America, Great Britain, and France posted in Bonn. The generals commanding each sector were diplomats, assisted by a minister-counselor, and the troop commanders were colonels.

General Jean Ganeval: A Hero Forged by the Ordeal of Deportation

Born on December 24, 1894, in Brest, Jean Joseph Xavier Émile Ganeval was admitted to the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr in 1914. In August, he enlisted for eight years as a soldier in the infantry. He first served in the 59th RI. Promoted to second lieutenant in 1915 and lieutenant in 1916, he ended the war as a captain with the Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 and the Legion of Honor.

From 1919 to 1920, he was part of the French mission in Berlin before being sent to the Levant in 1926, where he participated in operations against the Druze with the 2nd Bureau. Awarded the Croix de Guerre for Foreign Theaters of Operations (TOE), he was assigned in 1928 to the staff of the 168th RI in Worms in the Army of the Rhine occupation, then to Thionville after the 168th was converted into a fortress infantry regiment. He then served as a military attaché in the Baltic countries from 1933 to 1937. Promoted to battalion commander, he was given command of a battalion in the 39th RI in Rouen.

In 1940, he was sent to Finland to serve under General Mannerheim to command the French military mission. After the armistice between the Finns and the Soviets, he returned to France, where he was assigned to the 23rd RI as a lieutenant colonel in Toulouse. In 1941, he joined the clandestine movements Combat and Mithridate. Arrested in Lyon in October 1943 and incarcerated at Montluc prison, he was deported to Buchenwald. Thanks to his good physical condition and energy, he survived the deportation. Promoted to brigadier general, he received the Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 as well as the Rosette of the Resistance and returned to service in the FFA (French Forces in Germany) before being sent to Berlin as the representative of the commander of the French occupation army in Germany. On October 4, 1946, he became the military governor of Berlin.

This experience of deportation forged in him an unwavering determination and an intimate understanding of the struggle for freedom. A survivor of the camps, he perfectly embodied the spirit of a resistant France that refused to yield to oppression.

After the Liberation, General de Gaulle called on him for a mission of the highest importance: to command the French Forces in Berlin. This direct appointment testified to the trust placed in him by the leader of Free France, who recognized him as an exceptional man, forged by hardship and driven by an unyielding determination, one of the few Germanists with his experience in Germany as well as in the Baltic States and Finland.

General Ganeval became the French military governor of Berlin, a position he held with natural authority and a keen sense of responsibility. His presence in Berlin was set against the tense post-war backdrop, where the four Allied powers shared the administration of the former Reich capital.

The Context of Division and the Quadripartite Agreement

After the German surrender in May 1945, Berlin was divided into four occupation sectors among the Allies. The construction of the Wall in 1961 materialized this division, creating a physical border in the heart of the city. This unique situation required a constant military presence from the Western powers to maintain their access rights throughout the city.

The Quadripartite Agreement on Berlin, signed on September 3, 1971, between the USSR, the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, established the transit rights of Western forces throughout Berlin, including the Soviet sector. These agreements allowed the Western powers to maintain a symbolic but crucial presence in East Berlin, ensuring compliance with the commitments made during post-war negotiations.

The Crucial Role During the Berlin Airlift (1948-1949)

The Berlin Blockade officially began on June 24, 1948, when the Soviets progressively cut off all land and water access to West Berlin. This action followed the currency reform introduced in the Western zones on June 20, 1948, which Moscow perceived as a provocation.

The French authorities in Berlin found themselves in a particularly delicate situation: their sector, though smaller, housed a dense population entirely dependent on external supplies. In Paris, the government was more than reluctant. It must be said that at the time, 28% of the deputies in the National Assembly belonged to the French Communist Party (PCF). Two French diplomats took advantage of the presence of two Toucan aircraft from Maine on a mission to Tempelhof to return to the French zone with their families and furniture… Meanwhile, the British headquarters in Berlin decided that families would stay and contribute, particularly the women, by creating small vegetable gardens to show that the British would not abandon the people of Berlin.

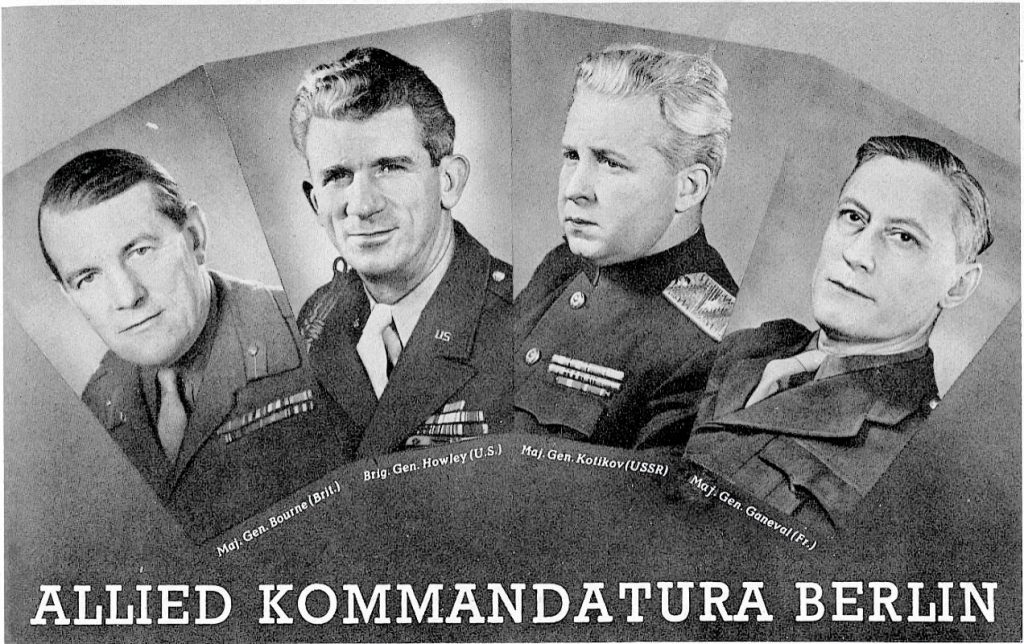

The credit for the airlift goes to General Lucius D. Clay, with two strokes of genius from Air Commodore Rex Waite and General Jean Ganeval — Photos from US, BR, and FR Forces in Berlin

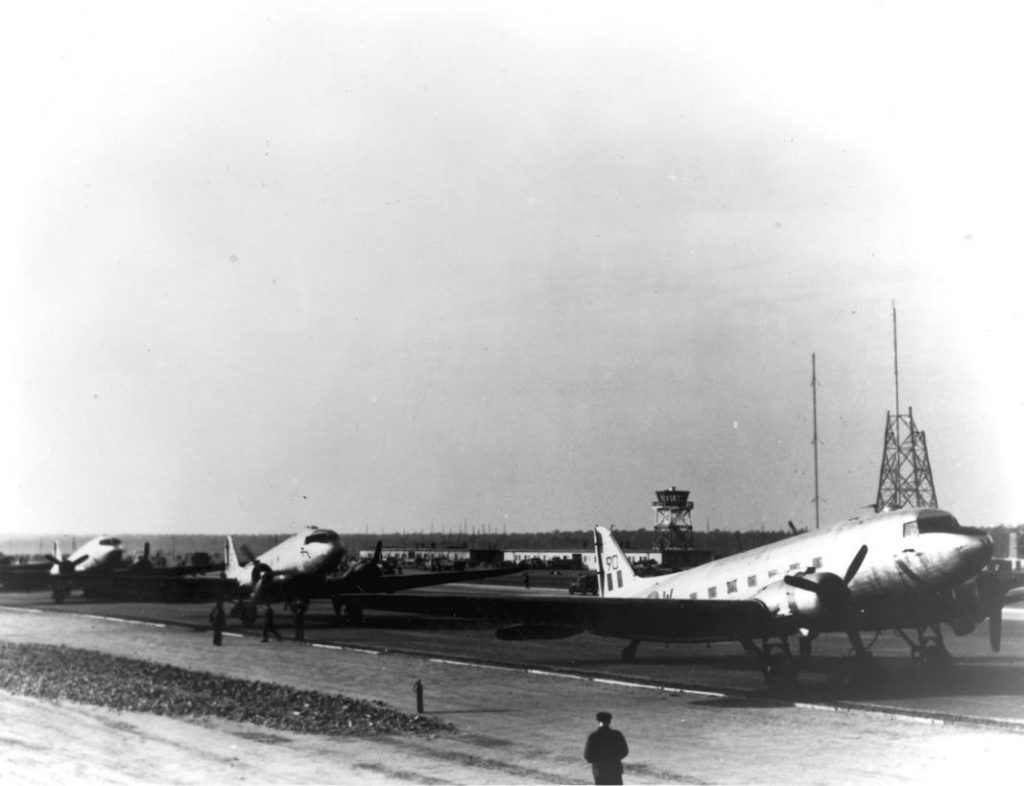

The idea of an airlift came from Air Commodore Rex Waite, the RAF commander in West Berlin. He proposed it to the British sector commander, Sir Brian Robertson, who immediately took him to see his American counterpart, General Lucius Clay. The idea appealed to him, as well as to the governing mayor of Berlin, Ernst Reuter. General Clay called Washington, which gave the green light: Operation Vittles was launched by the Americans, and Operation Plainfare by the British.

To involve the French, Sir Robertson went to see General Ganeval and essentially told him: « France is either with us, or it will be excluded from the Marshall Plan. » With such an argument, the general, who was personally in favor, quickly obtained the approval of the French authorities, confirmed by Georges Bidault. The decision to resist the blockade was then made jointly by the three Western powers, despite the risks of military escalation, as Washington had ruled out forcing the blockade by armed means.

The French Contribution to the Airlift

The French participation in the airlift was bound to be modest in quantitative terms, but thanks to General Ganeval’s initiative, it took on crucial political and symbolic importance. During the first few months, France committed six transport planes, mainly Junkers Ju-52s recovered from German forces and Douglas C-47s. French pilots flew the first daily rotations from bases in the French occupation zone, transporting food, medicine, coal, and essential raw materials. They also participated in night flights, which were particularly dangerous due to weather conditions and Soviet intimidation attempts in the air corridors. Any plane straying from the corridor could be shot down. The problem with the JU-52s was that they were completely unsuitable for this type of mission.

General François Mermet once told me that he had taken off from Orange for Algiers in a JU-52, and, pushed by headwinds, his Toucan ended up in Italy…

Furthermore, these planes were not equipped for flights without visibility. Several times, they ventured outside the very strict air corridors. They therefore posed more of a threat to the Allies, who mainly used C-47s… As a result, France, which had only a few C-47s (the Toucans had all been sent as reinforcements to Madagascar, as had those from Air France, which had been requisitioned), decided to provide ground support instead.

The British had their airfield at Gatow and the Americans at Tempelhof. France had none. General Ganeval decided to create an airfield next to the Quartier Napoléon in Tegel on a former German airship base from the First World War. The Russians had proposed a swampy piece of land north of Berlin…

Under General Ganeval’s leadership, the project was launched urgently on August 5, 1948. France had a train station in Berlin-Tegel; it would now have its airfield in Tegel, opposite the Quartier Napoléon, the FFB headquarters. The problem was that on the site of the potential main runway stood two Russian radio towers broadcasting Moscow’s propaganda, which prevented the creation of a long runway.

General Ganeval wrote to his Russian colleague. No response. The general convened his staff, dictated a letter, and had it hand-delivered to the Russian general, along with an ultimatum: you have 48 hours to dismantle your towers and repatriate your men. At 8:00 AM, I will have the towers blown up.

The Russians laughed it off, thinking he would never dare. They didn’t know him well. The evening before, the general had urgently summoned his American and British colleagues to the Quartier Napoléon for 7:30 AM sharp, without specifying the reason for the invitation. At the officers’ mess, they were received with their teams, served coffee, and chatted a bit. At 7:56 AM, General Ganeval stood behind a microphone. He greeted them and said he had summoned them to share an important decision. The suspense was total. At 7:59 AM, the general said a few more words, looked at his watch, and suddenly two huge explosions were heard.

All hell broke loose. General Ganeval, unperturbed, then told them, « Gentlemen, this is why I invited you. I wanted to inform you that the two Soviet towers were dynamited by our engineers on my order. »

On-site since five in the morning, the Russian sentries wondered what these French military engineers were up to, setting up a security zone after mining the towers. The Russians refused to believe it but finally understood it was serious and left the towers just minutes before the explosion. Promise kept, not a stone was left standing.

Two days later, at the Allied Kommandatura, Lieutenant General Kotikov, the general’s furious Soviet counterpart, asked him, « How could you have done that? » General de Ganeval replied unflappably, « With dynamite, my dear fellow. »

In West Berlin, this French general became a hero overnight. On the day of his departure, the population of Berlin formed a guard of honor along the road from his headquarters to the French military train at the Berlin-Tegel station.

Promoted to major general in 1950, General Ganeval was assigned on October 1, 1950, as the French High Commissioner to the Allied Military Security Board in Koblenz. On October 9, 1951, he was appointed head of the French delegation to the conference of experts on security controls in Germany. He then held several positions from 1951 to 1954: head of the private military staff of the Minister of Defense, Georges Bidault, then of René Pleven, before being appointed to the Élysée as head of the military cabinet of President René Coty (1954-1959). And in 1958, he was the one who would bring General de Gaulle back to power…

The Strategic Innovation of Berlin-Tegel

France may not have had military transport planes, but it had arms and brains. It received a new-generation radar, the most recent developed in the United States and not yet deployed, which allowed for all-weather flying. This ultra-modern radar, operated by Americans and French, made it possible to multiply flights to and from Berlin—two planes per minute, 24/7, would land or take off from Berlin, thanks to Tegel.

Berlin-Tegel Airport was built in record time. Men and women, paid for their work, toiled day and night to deliver Berlin’s largest runway to the Allies. It is thanks to Tegel that the Berlin Airlift became the most gigantic airlift in history.

It is worth remembering that during this period, the Soviets had warned the Allies: any aircraft that strayed from the strict limits of the air corridors would be shot down. Worse still, « Soviet military aircraft began to violate West Berlin’s airspace and harass, or what the Russian military called ‘buzzing,’ flights to and from West Berlin. » Thus, « on April 5, a Soviet Air Force Yakovlev Yak-3 fighter collided with a British European Airways Vickers Viking 1B airliner near RAF Gatow airfield, killing all passengers on both aircraft. » This event, later dubbed the « Gatow air disaster, » is reminiscent of the situation faced by the countries of Northern and Eastern Europe today.

Stalin had decided to starve West Berlin, just as he had done in Ukraine with the Holodomor. If the Allies had not put pressure on France, Paris would have displayed a complicity for which we would still be paying the consequences.

A Remarkable Technical Feat

The construction of Tegel Airport remains a French achievement. The most significant and lasting French contribution to the airlift is unquestionably the construction of Tegel Airport in the French sector, launched six weeks after the blockade began, mobilizing thousands of German workers—men and women, all paid—and French soldiers working in shifts day and night.

« It was the first time that air power alone would win a conflict. »

Construction began on August 5, 1948, and was completed remarkably quickly on November 5, 1948, with the creation of a 5,500-foot runway. Tegel Airport, built in record time on a former training ground, became operational and was the third airport used to supply West Berlin.

An Act of Courage: The Destruction of the Soviet Antennas

The most spectacular episode of this undertaking remains the destruction of the two powerful antennas of Radio Berlin, a propaganda station controlled by the Soviets, which stood on the land chosen for Tegel. Ganeval personally made the decision to have them dynamited by French engineers, ending the broadcasts of « the most powerful radio station in Germany. »

This act of bravery, which could have triggered a major diplomatic incident with the USSR, testifies to General de Ganeval’s determined character and his refusal to yield to Soviet pressure. The people of Berlin immediately saw it as the action of a courageous man of his word, who did not hesitate to take risks to defend French interests and the freedom of West Berlin.

This remarkable technical achievement significantly increased the airlift capacity to Berlin, with the construction of what was then the longest runway in Europe, measuring 7,966 feet (2,428 meters) long.

Popular Recognition and Legacy

The inauguration of the French train station in Tegel on December 6, 1947, in the presence of General Ganeval, symbolically marked the French commitment to the defense of Berlin. But it was during the Berlin Blockade that General Ganeval truly achieved the status of a popular hero.

For all Berliners in the French sector, « Ganeval is the general of the blockade. » When he left his post, the people of Berlin showed him touching gratitude: « Grateful Berlin did not want to let General Ganeval, its defender, leave, » headlined Le Monde. Schoolchildren gathered, « tumultuous and delighted, » waving their handkerchiefs as a farewell to the man who embodied French resistance to Soviet pressure.

A Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor, Jean Ganeval died in Paris on January 12, 1981, leaving behind the memory of a man who transformed his experience of deportation into a force for action in the service of freedom and French greatness.

Surveillance Missions During the Cold War

The little-known missions of the French forces were carried out within the framework of the Quadripartite Agreement.

1) Daily Patrols in East Berlin

French units of the 11th Chasseur Regiment (11e RC) and the 46th Infantry Regiment (46e RI) were responsible for securing the sector. The 46e RI, specializing in urban combat, and the 11e RC, experts in reconnaissance, jointly ensured the surveillance of the French sector of Berlin from 1947 to 1989. These two regiments were among the few formations in the French army that could permanently maintain their staffing levels for these delicate missions, which required specific preparation and in-depth knowledge of the Berlin terrain. In addition to these « show the flag » missions, the 2nd Bureau conducted daily six-hour patrols in the Soviet sector of Berlin.

2) The French Military Liaison Mission (MMFL)

In parallel with the Berlin patrols, the MMFL, based in Potsdam, operated in East Germany under the military liaison agreements between the occupying powers. In the immediate post-war period, 1946-1947, three bilateral agreements were made between the Western powers and the USSR, establishing the legal framework for these missions. This military unit specializing in military intelligence was not attached to the SDECE (External Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service). In Berlin, the services sometimes shared tasks and exchanged information to keep their target files up to date.

Initially housed in villas in Potsdam under close Soviet surveillance, this mission later had to adapt to geopolitical changes. The members of the MMFL « took refuge in West Berlin, while still maintaining » some of their activities in Potsdam. On several occasions, serious incidents occurred between MMFL teams and the MfS (Stasi), supported by the NVA (East German Army). One example:

On March 22, 1984, Warrant Officer Philippe Mariotti was driving an MMFL patrol car with Warrant Officer Jean-Marie Blancheton and Captain Jean-Paul Staub on a reconnaissance mission to observe the joint « JUG 84 » exercise of the 11th Motorized Rifle Division with Polish and Soviet armed forces. Their armored Mercedes was blocked by members of the MfS and the NVA near the Otto Brosowski barracks and trapped between two Ural 375 trucks. WO Mariotti died instantly, Captain Jean-Paul Staub was seriously injured and transported to the hospital in Halle. WO Blancheton, slightly injured, refused any treatment in a hospital. (Source: Theatrum Belli).

Active for 43 years, the MMFL was responsible for several first detailed observations of Soviet military equipment, operating alongside the British (BRIXMIS) and American missions. Two officers from the French Military Liaison Mission regularly observed Soviet troops in East Germany, thus contributing to Western intelligence.

The Impact and Legacy of the French Forces: The Transformation of Franco-German Relations

The Berlin experience profoundly transformed Franco-German relations. The French forces, initially perceived as occupiers, gradually became protectors in the eyes of the Berlin population. This major psychological evolution helped lay the foundations for the Franco-German reconciliation that would flourish in the 1950s.

French cultural and educational programs in Berlin created lasting bonds between the two peoples, fostering the emergence of a new generation of Francophile Germans. These privileged relationships would later facilitate negotiations on the European Coal and Steel Community.

Consolidation of the Western Alliance

The Berlin Airlift was the first major test of Western solidarity in the Cold War. French participation, despite its limited means, demonstrated Paris’s commitment to defending democratic values and strengthened its credibility with its allies.

This shared experience accelerated France’s integration into Western defense structures, culminating in French membership in NATO in 1949. It also influenced French European policy, steering Paris towards a more Atlanticist approach.

A Lasting Legacy

Tegel Airport, built by the French under the leadership of General Ganeval, became one of the most enduring symbols of Berlin’s resistance. Used for decades as the main civilian airport for West Berlin, it perpetuated the memory of the French contribution to Berlin’s freedom. The airport was named after aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal and became the fourth busiest airport in Germany, with over 24 million passengers in 2019.

The French Forces in Berlin maintained a continuous presence until German reunification in 1990, testifying to the French commitment to the defense of West Berlin. This 45-year presence constitutes one of the longest French military missions of the post-war era.

Conclusion

The establishment and operation of the French forces in Berlin between 1945 and 1994 exemplify France’s geopolitical transformation after the Second World War. From an occupied and humiliated nation in 1940, France became an occupying power in 1945, then asserted itself as an indispensable partner in the Western alliance during the Berlin Airlift.

General Jean Ganeval perfectly embodies this French renaissance: a deportee and camp survivor, he found in this ordeal the strength to serve his country with exemplary dedication. His time in Berlin, marked by the audacious creation of Tegel and the destruction of the Soviet antennas, made him a legendary figure of the nascent Cold War.

The testimonies of former soldiers perfectly illustrate this reality: while attention often focused on the American and British sectors, the French forces maintained an active and professional presence, contributing discreetly but effectively to the stability of this city, a symbol of European division.

These daily missions, through their regularity and professionalism, helped maintain the fragile balance that characterized Berlin during the Cold War. They testify to the French commitment to defending Western values, even in the most tense conditions of the East-West confrontation, marking the emergence of a new France: European by vocation, Atlantic by necessity, and reconciled with its former German enemy through historical pragmatism.

Joël-François Dumont

See Also:

- « Les Forces Françaises de Berlin (1945-1994) » — (2025-0928)

- « Von Besatzern zu Beschützern: die FFB in Berlin (1945-1994) » — (2025-0928)

- « From occupiers to protectors, the French Forces in Berlin: (1945-1994) » — (2025-0928)

Sources

[01] Général Silvestre de Sacy, Hugues, former head of the French Air Force Historical Service in European-Security : « Participation de l’Armée de l’Air au pont aérien de Berlin » (2019-0421) — & French Forces in Berlin – Wikipedia.

[02] « Berlin-Tegel 1948 : Le coup de génie français » — (2025-0927) & French occupation zone in Germany – Wikipedia.

[03] Institut de stratégie comparée : « Le renseignement militaire français face à l’est ».

[04] Wikipédia : « Accord quadripartite sur Berlin ».

[05] Centre Virtuel de la Connaissance sur l’Europe : « Accord quadripartite sur Berlin (Berlin, 3 septembre 1971) »

[06] Rubble to Runway: The Triumph of Tegel : National Museum of the US Air Force.

[07] Berlin Tegel Airport : Wikipedia.

[08] Institut de stratégie comparée : « Le renseignement militaire français face à l’est ».

[09] ACPGCATMTOE-VAL.FR : « Secteur français »

[10] La Liberté : « Berlin. vol au-dessus d’un nid d’espions », Pascal Fleury, 18 novembre 2019.

In-depth Analysis:

From occupiers to protectors, the French forces in Berlin fundamentally changed the game. Initially sidelined after WWII, France carved out its own sector, becoming a key player. They weren’t just soldiers; they were city-builders and denazification agents.

Then came the 1948 Soviet blockade, their defining moment. While the U.S. and Britain owned the skies, France made its stand on the ground. Their audacious move: building an entire airport, Tegel, in a stunning 90 days.

This wasn’t just construction; it was a strategic masterstroke. Tegel broke the back of the Soviet siege, ensuring the airlift’s success. It became a legendary symbol of French resolve and ingenuity.

For nearly 50 years, they were more than a garrison. They were spies, diplomats, and crucial partners in the Cold War’s hottest flashpoint. They transformed old enemies into steadfast allies. The French didn’t just occupy Berlin; they helped save it and secure its freedom.