In the smoking ruins of 1945 Berlin, the French gendarmes arrived as an occupation force. Landing on July 3rd in the Wedding and Reinickendorf sectors, they set up at Camp Foch with a clear mission: to impose order on a vanquished Nazi capital, ensure denazification, and combat all forms of trafficking that thrived in the devastated city.

But their status would quickly change. After an “Iron Curtain” fell across Europe, the Soviet blockade of 1948-1949 transformed them from occupiers into protectors, defending in West Berlin a fragile island of freedom in the heart of communist territory. The construction of the Wall in 1961 then threw them onto the front lines of the Cold War, fully integrating them into the Allied shield, patrolling along the infamous “death strip” in a state of permanent alert.[01]

A Forgotten Saga (1945-1994)

Table of Contents

par Joël-François Dumont — Berlin, October 09, 2025

Introduction

The 1948-1949 blockade was a game-changer: troop numbers increased, and a post was opened at Tegel Airport. Originally 535 non-commissioned officers strong, the garrison later dwindled, falling to 360 in 1952 and then below 300 after 1968. That year, a major restructuring was launched with the creation of a company of gendarme cadets at the Quartier Napoléon.[01]

The construction of the Wall in 1961 demanded heightened vigilance: reinforced patrols, a permanent state of alert. Integrated into the Allied defense, the gendarmes participated in regular military exercises.[01]

The Berlin Wall in 1961 thrust them onto the front lines of the Cold War. They became a crucial element of the Allied shield, patrolling the infamous “death strip” and maintaining a permanent state of alert.[01]

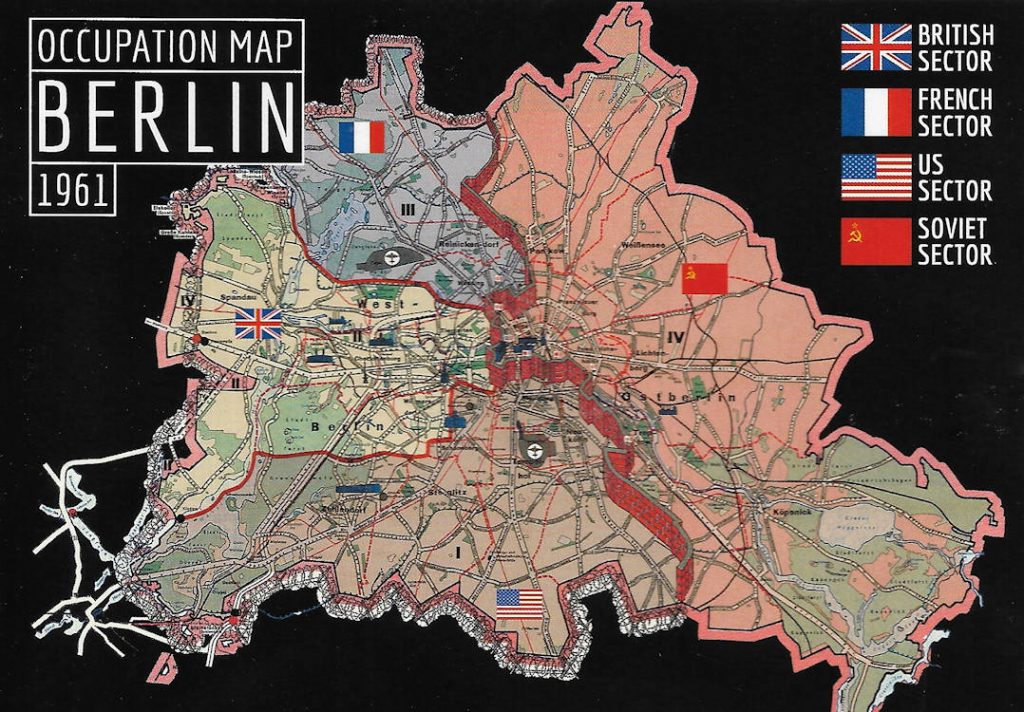

This “Wall of Shame” separated the French, British, and American Allied sectors (West Berlin) from the Soviet sector (East Berlin).

Between West Berlin and West Germany lay the Soviet occupation zone, which included:

- on the West Berlin side, a first “death zone,” and

- on the West German side, from north to south, a second death zone with watchtowers, mines, and armed border troops (GREPO) with dogs drugged with pepper (to keep them more vigilant) to prevent East Germans from fleeing “the homeland of the workers and peasants”…

The Allies transited between West Berlin and the American, British, or French zones through the Soviet zone—whether by air, road, or rail—only through corridors guarded day and night, where East German border soldiers would shoot with or without warning.

For decades, their missions were unique: to secure vital French and Allied installations, but also to guard Spandau Prison and its last inmate, Rudolf Hess.

However, the sudden fall of the Wall in 1989 marked the end of their world, making their presence of nearly 50 years obsolete overnight.

In 1994, the last gendarmes left Berlin, their watch completed. They had made a remarkable journey: from victors to guardians, and finally, to guests of honor leaving a sovereign and reunified Germany. Their legacy is a testament to half a century of unfailing vigilance on the frontier of freedom.

The Creation of the Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment (D.G.B.)

From 1945 to 1994, the French Gendarmerie Detachment of Berlin (D.G.B.) represented a unique chapter in the Gendarmerie’s history,[01] intimately linked to the fate of the German capital. Arriving in July 1945 amidst the ruins of the Wedding and Reinickendorf districts, the French gendarmes initially took on the role of an occupying force, tasked with denazification, hunting war criminals, and combating trafficking in a devastated city.[01]

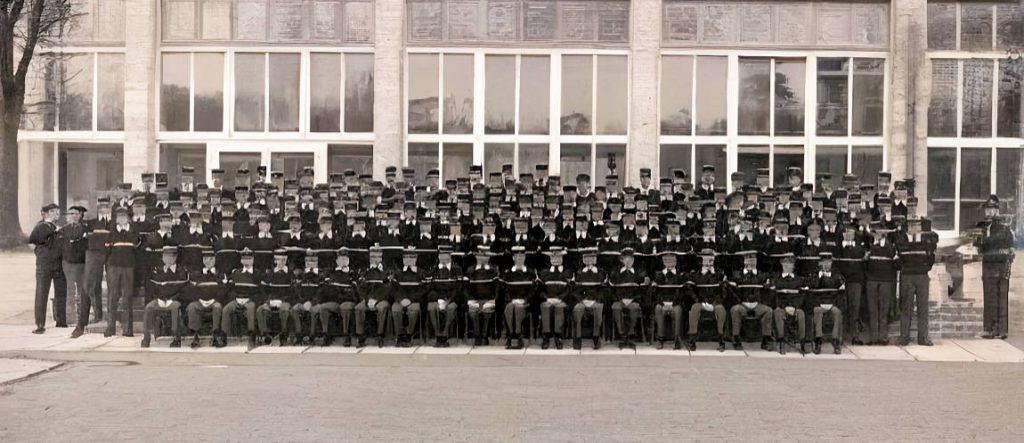

Photo © Gendarmerie Nationale (Berlin)

Their fundamental missions, defined as early as 1946, covered judicial, administrative, and military police duties, as well as maintaining order and securing Allied installations [01]

1: Testimony of Battalion Commander Benoît Haberbusch

The Cold War context radically transformed their status. The 1948-1949 blockade, a true shock, led to an increase in personnel and shifted their perception from that of occupiers to protectors in the eyes of the Berlin population. The D.G.B.’s organization continuously adapted to international tensions and national needs, marked by personnel transfers to Indochina and North Africa, the construction of the Wall in 1961 which increased surveillance duties, and a profound restructuring after May 1968. The latter saw the dissolution of the detachment as a corps and the creation of a company of gendarme cadets—a unit that was both operational and a showcase for the gendarmerie.[01]

Among their permanent tasks, the gendarmes carried out judicial police missions with expanded powers and security missions, including guarding Spandau Prison from 1947 to 1987, where Rudolf Hess was held.[01]

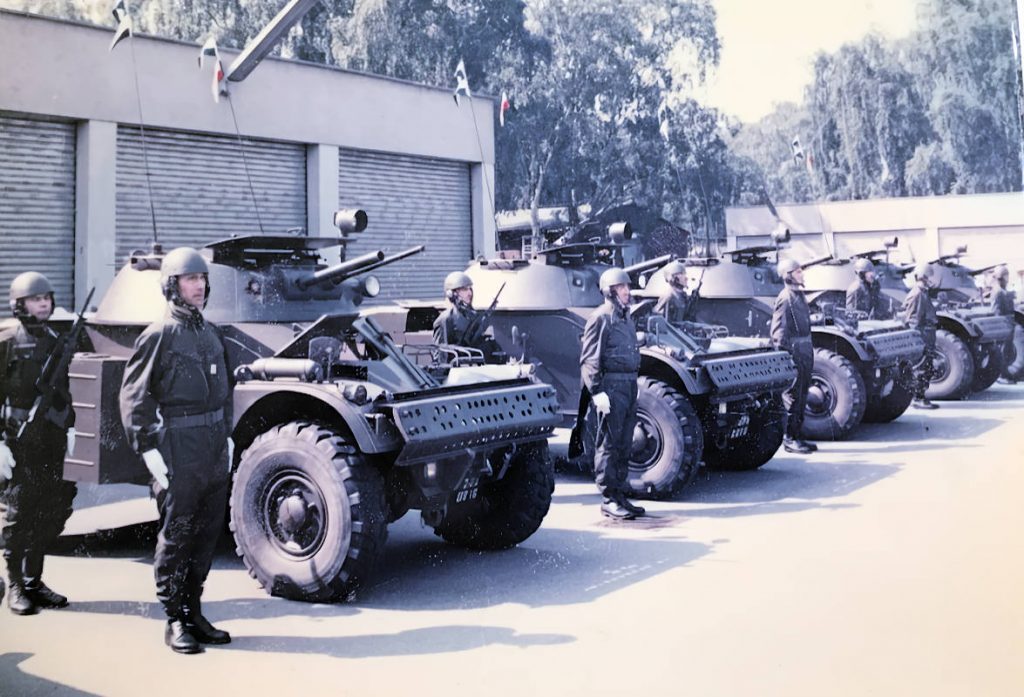

Integrated into the Western defense apparatus, they participated in numerous inter-allied maneuvers, always on high alert.

The fall of the Wall in 1989, a surprise to everyone, rendered their mission obsolete. The detachment was progressively dismantled, the gendarme cadet company was dissolved in 1991, and the last gendarmes left Berlin in 1994. The article concludes on the remarkable metamorphosis of this unit, which in half a century went from the status of occupier to that of protector, ultimately becoming an invited force in a territory that had regained its sovereignty.[01]

2: Berlin, Theater of the Absurd: The Missing Pages of the French Gendarme (1945-1994)

The Kepi in the Ruins

July 1945. Berlin is no longer a city, but an open-air scar, an apocalyptic landscape where ghosts wander between the skeletons of gutted buildings.[02] Into this end-of-the-world setting, where 70% of the land has become cemeteries, the first French gendarmes arrive.[03] Their arrival is an anomaly. Victorious but late to the party, France had to fight hard to secure its place at the table of the great powers. General de Gaulle had to use all his political weight with a pragmatic Winston Churchill for the latter to agree to cede two districts from his own sector.[03] This entry through the side door immediately conferred upon the French a precarious status, that of the “poor relations of the Big Three.”[04]

Their initial mission, however, is clear: to impose republican order in the heart of chaos. It involves uncovering clandestine weapons depots, hunting down the last war criminals, and dismantling secret Nazi organizations like “Edelweiss” and to combat all forms of trafficking (black market).[01]

They must also curb a sprawling black market, born of the absolute misery that pushes Berliners to trade their last possessions for something to survive on.[01] But for these gendarmes, many of whom had experienced the humiliation of the German Occupation in France just months earlier, the situation is one of incredible psychological complexity.[02] They are at once victors and bearers of the fresh memory of being vanquished.

This schizophrenic position is exacerbated by their material destitution. Less well-equipped than their American or British counterparts, they are forced to carry out massive requisitions of housing and equipment, which creates immediate friction and palpable resentment among the German population.[04] The French occupier is an uneasy occupier, aware of its legitimacy but insecure about its means, establishing from the outset a relationship built on mistrust and insecurity.

Women and sometimes even teenagers will participate in human chains to clear away the rubble. The priority was to restore the city’s ability to feed, house, and transport its residents by repairing roads and municipal services.

The French occupier is an insecure occupier, aware of his legitimacy but self-conscious about his resources, immediately establishing a relationship based on mistrust and insecurity.

| Period | Major Cold War Event | Evolution of the D.G.B. and its Missions | Key References |

| 1945-1947 | Start of the quadripartite occupation | Arrival of the gendarmes. Occupation mission, denazification, fight against the black market. Status of “uneasy occupier.” | [14] |

| 1948-1949 | Berlin Blockade by the Soviets | Construction of Tegel Airport. Radical transformation into a protective force. Reinforcement of personnel. | [13] |

| 1950-1960 | Integration of West Germany into NATO | Normalization of judicial police and law enforcement missions. Start of the guard duty at Spandau Prison. | [01] |

| 1961 | Construction of the Berlin Wall | Intensification of patrols along the Wall. Increased surveillance and alert duties. | [12] |

| 1968 | May 1968 events in France | Profound reorganization. Dissolution of the D.G.B. as a corps. Creation of the gendarme cadet school. | [01] |

| 1970-1980 | Détente and Quadripartite Agreement | Focus on core missions. Maintenance of broad judicial prerogatives. Cooperation with Berlin police. | [12] |

| 1987 | Death of Rudolf Hess | End of guard mission at Spandau Prison, which is demolished. | [15] |

| 1989 | Fall of the Berlin Wall | Total surprise for the personnel. The D.G.B.’s historic mission becomes obsolete. | [16] |

| 1990-1994 | German Reunification | Change of status to invited force. Progressive dismantling of units and final departure in September 1994. | [12] |

Chapter 1: From Uneasy Occupier to Unexpected Protector (1945-1949)

The first years are a purgatory. The relationship between the gendarmes and the Berliners is tense, marked by the necessities of occupation and the vivid memory of the war.[04] Then, on June 24, 1948, the world shifts on its axis. Stalin, exasperated by the introduction of a new currency in the Western sectors, decides to asphyxiate West Berlin. All land and water access routes are cut off. The blockade begins.[03][07] For the two million West Berliners and the Allied garrisons, it is the start of a peacetime siege.

This event is the crucible in which the Gendarmerie Detachment of Berlin will forge its true identity. While the Americans and the British take to the skies with an airlift of unprecedented scale, the French, whose aerial contribution is more symbolic, will play their trump card on the ground.[03][08] General Jean Ganeval, the French military governor, a man hardened by the ordeal of deportation to Buchenwald, makes a wildly audacious decision: to build a third airport to relieve the other two. It will be at Tegel, in the French sector.[03]

The construction site is a stroke of strategic genius and a human feat. In just 90 days, 19,000 German workers, 40% of whom are women, work day and night to raise the longest runway in Europe from the ground.[03][09] But a major obstacle stands in their way: two immense Soviet radio antennas, planted right in the middle of the future airport, broadcasting Moscow’s propaganda. Ganeval politely asks his Russian counterpart to dismantle them. No response. The French general then sends an ultimatum: if the towers are not gone within 48 hours, he will have them blown up. The Soviets scoff. On November 16, 1948, at 8 a.m., as he is hosting his American and British colleagues for coffee at the Quartier Napoléon, two formidable explosions shake the north of Berlin. Ganeval, unperturbed, announces to them: “Gentlemen, the two Soviet towers have just been dynamited by our sappers on my order.”[03]

This spectacular act of defiance changes everything. Overnight, the “poor relations” become heroes. The unloved occupiers transform into “protecting powers.”[02][10] For the Berliners, the airlift planes are “Rosinenbomber” (raisin bombers), and the French who dared to stand up to the Soviet Bear are saviors. This popular recognition gives the gendarmes a legitimacy and pride that their initial status had never afforded them. Their missions change: they no longer just hunt traffickers; they secure the approaches to the vital airport, protect polling stations during elections held under Soviet threat, and prepare to slow down a potential invasion.[01] The crisis is so intense that their families are even evacuated in 1949.[01] The kepi is no longer just a symbol of French authority; it has become an emblem of Berlin’s freedom.

Chapter 2: Life in Khaki, Blue, and Tricolor: A Miniature France (1950-1989)

For nearly forty years, the French community in Berlin would live in a bubble, a world apart nestled in the heart of the most explosive city on the planet. It is a miniature France, with its own codes, places, and rituals, a tricolor island hundreds of kilometers behind the Iron Curtain.

The beating heart of this world is the Quartier Napoléon. A former and gigantic Hermann-Goering-Kaserne, the complex is renamed in memory of the Emperor’s entry into the city in 1806.[02][11] It is the military and administrative nerve center of the French forces.[11][12] Testimonies from veterans describe a surprising place, far from the austere image of a traditional French barracks. It is a true city within a city, with its residential-style buildings, its circular road as wide as a highway, its military hospital, two swimming pools, a gymnasium, and multiple sports fields.[06][13][14]

If the Quartier Napoléon is the work-place, the Cité Foch is the place of life. Built in the 1950s, this residential area is a French enclave where everything is done to recreate a feeling of home.[15][16] The families of military and civilian personnel live there in a completely French-speaking envi-ronment. There are French schools, from the Collège Voltaire to the lycée, a church (Sainte-Geneviève), a cinema, and above all, an économat, a small supermarket where one can find products from France.[16]

Street name signs in French and German in the Cité Foch

The streets are named after Molière, Diderot, Montesquieu, or Charles de Gaulle, reinforcing this impression of expatriation in a vacuum.[15][17] This life, though comfortable, is also profoundly insular. As one former resident recounts, “there was absolutely no reason to make an effort to go outside.”[16]

The vital link with the motherland is provided by a legendary institution: the French Military Train to Berlin (TMFB). This night train, which connects Strasbourg to the French station in Tegel three times a week, is the community’s “umbilical cord.”[18] For the tens of thousands of young conscripts who take it each year, the nearly 200-kilometer journey through the hostile territory of the GDR is a rite of passage, a slow and anxious plunge into the world of the Cold War.[11][14]

On a daily basis, the gendarmes’ missions are multiple and unique. Unlike other Allied military police, the D.G.B. retains broad judicial police prerogatives, its jurisdiction extending to all French citizens in Berlin, but also to Germans involved in cases concerning them.[01] The structure evolves, from a simple gendarmerie section to a “mobile judicial police platoon,” then to a “provost company” in 1967, a complete police force serving the French community.[01]

Their days are punctuated by tense patrols along the Wall, with the chilling order: “at no time and under no circumstances will fire be opened until the Allied Forces have themselves come under fire from the Soviets.”[01] In 1968, a new peculiarity appears with the creation of the gendarme cadet company at the Quartier Napoléon. More than just a school, it is an operational combat unit, integrated into the city’s defense plans, and a “showcase for the Gendarmerie” whose students provide honor guards and participate in inter-allied sports competitions.[01][14]

This life is a permanent paradox. It is a gilded cage, where material comfort and camaraderie create an atmosphere of relative carefree-ness, but a cage whose bars are made of bricks and barbed wire, and whose guards are the actors in a possible nuclear apocalypse. It is a provincial French life played out on the most dangerous stage of the world theater.

Chapter 3: The Tenant of Spandau: Guarding a Ghost (1947-1987)

Of all the missions entrusted to the gendarmes of Berlin, none better embodies the mix of historical tragedy and bureaucratic absurdity of the Cold War than guarding Spandau Prison. For forty years, from 1947 to 1987, the four victorious powers took turns every three months to mount a grand military guard in front of a red-brick fortress.[12]

The spectacle is utterly surreal. Each changing of the guard is an impeccable ceremony, a demonstration of force and martial rigor.[02] Yet, from 1966 onwards, this impressive deployment of American, British, Soviet, and French soldiers had only one single object: an old man. Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s former deputy, becomes the sole tenant of this immense prison designed for 600 inmates.[05][19] For the young French gendarmes, this mission is a chore. British parliamentarians would call it a “cruel military charade,” “boring in the extreme” for the soldiers.[20] Guarding a ghost in an empty fortress, that was the daily routine. Hess’s routine was immutable: wake up at 6:45 a.m., breakfast, walk in the garden, lunch, another walk, dinner, bedtime. And every day, armed soldiers watched him from watchtowers.[05]

But behind the bureaucratic farce lies a more complex human reality. The French Protestant chaplains, who accompanied the seven Nuremberg convicts and then Hess alone, provide a startling testimony. Far from the image of a madman that propaganda sometimes conveyed, they describe an “absolutely normal” man.[21] Pastor Charles Gabel, who forged a friendly relationship with him much to the Soviets’ dismay, is adamant: “He wasn’t crazy, not at all!”[21] This humanization of prisoner number 7 places the gendarmes in an untenable position. They are not just guarding a symbol of absolute evil, but a man, with whom some of their compatriots maintain ties of respect, even friendship.

Spandau Prison is a microcosm of the Cold War. It is a political theater where the actors perform a play whose meaning escapes them. The four powers are not guarding a man, but a memory, an idea of justice, and above all, their own status as victors. The Soviets, in particular, would oppose any release until the very end, seeing in Hess the last tangible symbol of their victory over Nazism.[22] For the French gendarme on duty, the mission is a daily confrontation with the legacy of World War II, the implacable logic of the Cold War, and the disturbing humanity of their prisoner. It was the Cold War distilled to its purest and strangest essence. On August 17, 1987, Rudolf Hess was found hanged in a garden shed. The charade ends. The prison is immediately demolished to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi pilgrimage site.[05]

Chapter 4: The Wall Falls, the Curtain Lowers (1989-1994)

On the evening of November 9, 1989, History, without warning, came knocking at Berlin’s door. For the French gendarmes, whose daily life had been paced for 28 years by the immutable presence of the Wall, the event is a shockwave. General Choquet, then second-in-command of the detachment, would later confirm: it was a “complete surprise.”[01] Veterans remember witnessing the unimaginable live: Trabants crossing checkpoints, the jubilant crowd, the end of an era.[06] In one night, forty-four years of mission, tensions, routines, and certainties become obsolete. The enemy has vanished. The Wall, that “mountain” that had structured their existence, is now just a pile of rubble sold to tourists.

Geopolitical events unfold at a breakneck speed. The Treaty of Moscow, signed in September 1990, ends the rights and responsibilities of the four powers over Germany.[02] The Allied Kommandatura, a symbol of the occupation, is dissolved. On October 3, 1990, Germany is reunified. The D.G.B.’s reason for being has evaporated.

Yet, the story is not quite over. At the request of the new German government, the French forces agree to stay until the last Russian troops depart. Their status changes one last time. After being occupiers, then protectors, they become an “invited force.[12] It is a bittersweet transition period, a long goodbye.

The units are dismantled one by one. The gendarme cadet company, which had trained so many young non-commissioned officers in this unique setting, closes its doors in February 1991.[01][14] By September 1, 1991, the D.G.B. has only 15 military personnel left.[01]

The final departure takes place in September 1994. On the 8th, President François Mitterrand attends the solemn farewell ceremony hosted by the German government for the Western forces. On the 28th, a final military ceremony is held at the Quartier Napoléon before it is handed over to the Bundeswehr and renamed Julius-Leber-Kaserne.[02][11] The last French military train leaves the Tegel station. The curtain falls. For the gendarmes of Berlin, the end of the Cold War is not an abstract geopolitical concept. It is the end of their world, the dissolution of a unique identity forged in hardship and camaraderie. Their departure is not a defeat, but the closing of a circle, the epilogue of a mission that, by its strangeness and duration, remains unparalleled.

Conclusion: Epilogue to a Singular Saga

The story of the Gendarmerie Detachment of Berlin is one of metamorphosis. Arriving in 1945 as representatives of a victorious but diminished power, in a city that did not expect them, the French gendarmes managed, through crises, to reinvent themselves. The ordeal of the 1948 Blockade transformed them from precarious occupiers into resolute protectors, giving them a legitimacy and a purpose that would never leave them.

For half a century, they were the actors and witnesses of an extraordinary history. They lived in a surreal French enclave, connected to the free world by a ghostly train. They patrolled along the most famous scar of the 20th century. They stood guard in front of a prison-theater where the final act of World War II was being played out. They embodied France’s presence at the hottest point on the planet, with a mix of military rigor, resourcefulness, and a certain irony in the face of the absurdity of their situation.

Their saga is singular because it trans-cends the simple military framework. It is a human story, that of nearly 100,000 French military personnel who served in Berlin, started families, forged bonds, and shared the fate of a city that, like them, had to learn to live on a fault line.[02] Their departure in 1994 closed a chapter, not on a note of conquest, but on that of a mission accomplished. In Berlin, the kepi of the French gendarme became, against all odds, one of the discreet but tenacious symbols of a preserved freedom.[23]

Caricature © European-Security

The image of French Gendarmes in Germany

From victors to guardians, French gendarmes accompanied Berlin on its journey to freedom for half a century. In Berlin, they are part of the landscape. In Germany, they enjoy a strong reputation: the German press highlighted their tenacity and support for the bereaved families after the crash of the Germanwings A320 on March 24, 2015, in the French Alps, which killed 150 people, including 72 Germans and 50 Spaniards, from 18 different countries.

At the time, under the leadership of General David Galtier, the various branches of the gendarmerie carried out an exceptionally large-scale operation to recover and identify the victims in extremely difficult conditions, enabling the families to begin the grieving process.

The Gendarmerie’s Excellence in the Face of the Unspeakable

In the deafening chaos that followed the crash, while the mountain still bore the scars of the tragedy, a silent battle began.

General Christophe Brochier stated it emphatically: the identification was a macabre puzzle. Confronted by the horror, the experts from the National Gendarmerie’s Criminal Research Institute (IRCGN) deployed surgical precision.

This was not mere grunt work; it was an obsessive quest for the truth to wrench each of the 149 victims from the anonymity of the disaster.

Founded by the visionary General Jacques Hébrard, the IRCGN has made its mark on the entire world. For Americans, the British, or Germans, it is not just a reference: it is the gold standard, the absolute pinnacle of forensic science, capable of making silence speak and restoring dignity to those who had lost it.

The Unquenchable Memory, an Oath of Remembrance

Ten years have passed. The pain remains untouched. On March 24, 2025, in Le Vernet, on this scarred earth turned sanctuary, time stood still. Nearly 400 people, with solemn faces and shattered hearts, gathered at the foot of the stele. It was not a simple ceremony, but a poignant communion, an act of defiance against oblivion. Words of comfort rose in a concert of languages—German, Spanish, English, Italian, Turkish, Arabic—united by a single, universal sorrow. Each tribute, year after year, is not a mere commemoration; it is a solemn pact against erasure. A promise etched in rock and into souls, so that the 150 lives cut down that day would never become just a number, but remain an eternal light in the memory of mankind

Joël-François Dumont

Sources

[01] « The Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment 1945-1994 » par le commandant Benoît Haberbusch — (2025-1010)

[02] Chroniques Seconde Guerre Mondiale, « French forces in Berlin from 1945 to 1994 ».

[03] European Security, « French forces in Berlin from 1945 to 1994 ».

[04] Berliner Monatsspiegel, « Marginalized. France as an occupying power in Berlin ».

[05] YouTube (Raconte-moi une histoire), « Rudolph Hess: 40 years in prison for Hitler’s successor ».

[06] Vive Berlin Tours, « The Quartier Napoléon, Berlin’s former French barracks ».

[07] European Security, « The French Forces in Berlin (1945-1994) (2) ».

[08] France Diplomatie, « Berlin in the Cold War / Blocus (1948-1949) ».

[09] AlliiertenMuseum, « The Berlin Airlift 1948-1949 »..

[10] France-Allemagne.fr, « Spiegelbilder // Reflets ».

[11] ACPG-CATM-TOE-VAL, « Quartier Napoléon ».

[12] ACPG-CATM-TOE-VAL, « Quartier Napoléon ».

[13] Anciens du 46e RI, « History of the Quartier Napoléon ».

[14] (Gendinfo), « Thirty years ago, the gendarmerie school in Berlin closed its doors. ».

[15] Wikimedia Commons, « Category: Cité Foch ».

[16] YouTube (France 3 Grand Est), « Berlin : la Cité Foch, un ancien quartier français à l’abandon ».

[17] Wikipédia, « Cité Foch ».

[18] Association pour l’histoire des chemins de fer (AHICF), « Book release: ‘The French Military Train from Berlin and its secrets (1945-1994)‘ ».

[19] Reddit, « Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s former deputy, stands in front of Spandau Prison…».

[20] Hansard (Parlement britannique), « Rudolf Hess ».

[21] Protestinfo, « French chaplains finally speak out about the Nazi war criminals they accompanied at Spandau Prison ».

[22] Reddit, « Rudolf Hess, Spandau Prison, 1985 ».

[23] The gendarmes represented a significant part of the French Forces in Germany: “In 1946, nearly 11,000 gendarmes were stationed across the Rhine. They were organized into four occupation legions and two intervention legions, in addition to the autonomous company in Saarland, the preparatory school in Horb, and the gendarmerie detachment in Berlin. The Berlin Gendarmerie School, which was open from 1968 to 1991, was also located in the heart of the French zone in the north-west of the German capital. Its students were scrutinized with particular attention: they represented the gendarmerie and its training programs in an inter-service and international environment. An officer was on duty every day to ensure that the student gendarmes complied with military rules.” Source: Source : Archives and Memory Department – Gendarmerie.

See Also:

- « Le détachement de gendarmerie de Berlin 1945-1994 (1) » — (2025-1008)

- « Das Gendarmeriekommando Berlin, 1945-1994 (1) » — (2025-1008)

- « The Berlin Gendarmerie Detachment 1945–1994 (1) » — (2025-1008)

- « Les gendarmes de Berlin : Mission impossible sur la Spree (2) » — (2025-1009)

- « The Gendarmes of Berlin: Mission Impossible on the Spree (2) » — (2025-1009)

- « Die Gendarmen von Berlin: Mission Impossible an der Spree (2) » — (2025-1009)

In-depth Analysis:

Arriving in 1945 in a Berlin in ruins, the French gendarmes were initially just the “poor relations” of the Allies—insecure occupiers, weighed down by their precarious status. Their mission: to impose order on a field of ruins, a monumental task for victors still fresh with the memory of defeat.

But the 1948 Blockade was their true genesis. Facing the Soviet Bear, French audacity—dynamiting radio towers to build Tegel Airport—transformed them. Overnight, the unloved occupiers became the acclaimed protectors of Berlin’s freedom, forging their legitimacy in a trial by fire.

What followed were forty years of a surreal existence: a “France in miniature” cut off from the world, where the daily routine was patrolling a concrete scar and guarding a ghost—Rudolf Hess, alone in the vast Spandau Prison. It was the Cold War’s theater of the absurd: a provincial life played out perpetually on the brink of nuclear apocalypse.

On November 9, 1989, History brought down the Wall, and with it, their entire reason for being. Rendered obsolete overnight, they finished their unique saga as an “invited force” before the final curtain call in 1994. Ultimately, their story is one of an unexpected metamorphosis: that of a French képi, arriving amid mistrust, that became a quiet but tenacious symbol of freedom on the world’s most explosive frontline.