Historian Laurence Saint-Gilles,[*] in her masterful article for Desk Russia, ‘The Russian Lobby in the United States,’ has accomplished an essential mapping effort.[01] With the precision of a political geographer, she traced the visible contours of Russian influence, revealing the topography of an American ‘Putin-sphere’ and its ‘long work of sabotage.’[01] Her analysis provides the indispensable framework for anyone seeking to understand how a nebula of interests aligned with Moscow has managed to establish itself at the very heart of American power.

In light of President Donald Trump’s statements and the appointment of high-ranking officials who are openly pro-Putin, Laurence Saint-Gilles has updated her analysis, using this map as a starting point for a deeper expedition, a foray into the unlit corridors and engine rooms of this vast influence enterprise.

The Washington Labyrinth: Investigating the Architects of Russian Influence

Starting from this macroscopic analysis, Laurence Saint-Gilles immerses us in a granular examination of the key operators, the specific mechanisms of infiltration, and, above all, the systemic vulnerabilities that they exploit with formidable efficiency. The objective is not to criticize, but to build on her foundations, by adding layers of quanti-tative data and recent, chilling case studies that underscore the depth and adaptability of the threat.

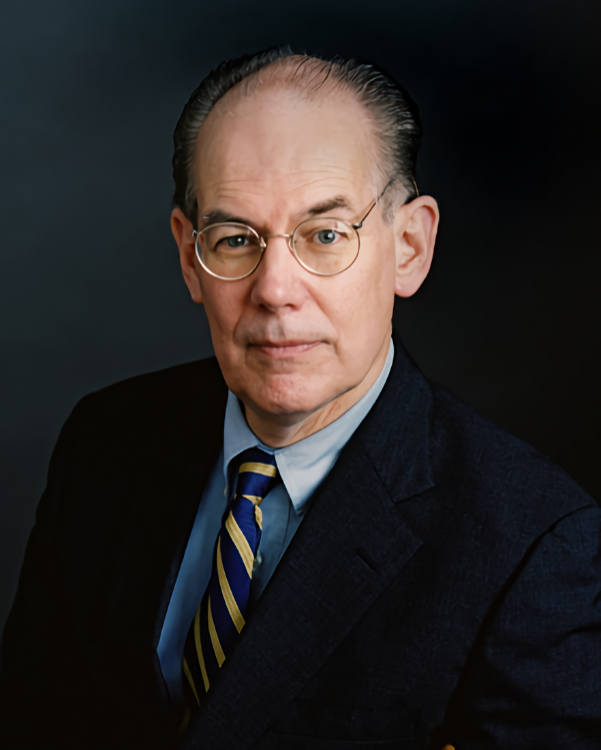

Laurence Saint-Gilles

— Photo © All Rights Reserved —

The tone is set: that of a serious investigation, enhanced by an appreciation for the audacity, sometimes bordering on the absurd, of the operations in question. To understand a labyrinth, it is not enough to look at it from above; one must dare to enter it. Editor’s note

Table of Contents

by Laurence Saint-Gilles — Paris, August 31, 2025 —

Introduction: Beyond the Kremlin’s Looking Glass

1. Anatomy of the “Putin-sphere”: From Spies to Useful Idiots, and the Agent at the Top of the FBI

The Russian lobby is certainly a “disparate nebula with fuzzy ideological contours,” a heterogeneous constellation populated by intelligence officers, agents of influence, and a cohort of “useful idiots” who, whether by conviction or naivety, serve the Kremlin’s objectives.[01]

This typology is fundamental, but to grasp the truly systemic nature of the threat, it is necessary to dissect the intelligence apparatus that constitutes the hard core of this nebula and to illustrate just how far corruption can infiltrate.

The Intelligence Apparatus Deconstructed

Behind the generic term “intelligence officers” lies a complex architecture of Russian services with distinct mandates but converging objectives in the United States. Understanding their respective roles is crucial to deciphering their operating methods.

- The SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service): Heir to the prestigious First Chief Directorate of the KGB, the SVR is the main civilian foreign intelligence agency. Its specialty is human intelligence (HUMINT), conducted both under traditional diplomatic cover from embassies and consulates, and via “illegal” agents – unofficial agents, without diplomatic immunity and with no apparent link to Russia, who have been inserted into American society for a long time.[02][03] The SVR is the master of sophisticated, long-term penetration operations, as evidenced by its involvement in the massive SolarWinds cyberattack in 2021, which compromised thousands of American governmental and private networks.[04]

- The GRU (Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff): The Russian military intelligence service is known for its aggressive, high-risk, and often “brazen” operations.[03][05] Its portfolio is vast: from tactical intelligence on the battlefield to commanding special forces (Spetsnaz), as well as disruptive cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns. It was the GRU that was identified as the main culprit in the hacking of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in 2016 and the NotPetya malware attacks in 2017, demonstrating a propensity for direct and destabilizing action..[05][06]

- The FSB (Federal Security Service): Although its primary mission is internal security, the FSB has considerably expanded its mandate abroad, particularly in the countries of the former Soviet Union, via its “Fifth Service.”[03] The FSB has been involved in assassinations, cyberattacks, and influence operations outside of Russia’s borders, illustrating the growing blurring of the lines between internal security and external power projection.[04][07]

Case Study on the Corrosion of Elites: Charles McGonigal

While the existence of these services is no surprise to anyone, the “Putinization” of American elites finds its most spectacular and disturbing validation in the Charles McGonigal case. This case is not a simple spy anecdote; it is the demonstration that the gangrene can reach the top of the American counterintelligence apparatus.

Charles McGonigal was not a second-rate agent. He was the Special Agent in Charge of the Counterintelligence Division of the FBI’s New York office, the man whose mission was precisely to hunt down Russian spies on American soil.[08] However, shortly after retiring in 2018, he began working for the sanctioned oligarch Oleg Deripaska, a businessman described by American authorities as an agent acting on behalf of Vladimir Putin.[08][09]

McGonigal‘s modus operandi reveals an intimate knowledge of the methods he was supposed to be fighting. To conceal payments from Deripaska, he used a network of shell companies, forged signatures on contracts, and coded language in his electronic communications, carefully avoiding naming his client.[08][10] His mission? To investigate a rival oligarch, in direct violation of the American sanctions that he himself was tasked with enforcing.[09][11]

The irony of this betrayal is abysmal.

Oleg Vladimirowitsch Deripaska — Photo Anton Poper

During his years at the FBI, McGonigal had not only overseen investigations into Deripaska, but he had also received classified briefings detailing the reasons why this oligarch would be placed on the sanctions list.[11][12]

He knowingly crossed the red line, motivated by the lure of profit, hoping to build a new lucrative career on the ruins of his oath. His sentence of 50 months in prison is the dark epilogue.[08][09]

The McGonigal affair is much more than a story of individual greed. It is a symptom of a critical systemic vulnerability within the American national security establishment: the lucrative transition from public service to the private sector.

The classic espionage scenario imagines external pressure being exerted on an active agent. The McGonigal case reveals a more subtle, internal threat. He was not a classic “mole”; he was a high-ranking official who monetized his access, his expertise, and his credibility after leaving office. This highlights a sophisticated targeting strategy on the part of America’s adversaries: identifying powerful officials approaching retirement, potentially motivated by financial gain, is a lower-risk, higher-reward approach than trying to recruit an active agent.

The famous “revolving door” between intelligence agencies and private consulting firms is no longer just an ethical problem; it has become a gaping counterintelligence loophole. Adversaries are not just buying information; they are buying the influence, credibility, and procedural knowledge of the very people who built America’s defenses.[13][14]

2. The Pioneers of the Labyrinth: How to Infiltrate America with a PhD and a Smile

Without a doubt, Edward Lozansky and Dimitri Simes appear as key historical figures, pioneers who, as early as the 1970s and 1980s, were able to infiltrate American conservative circles and lay the foundations for the current lobby.[01]

Their respective journeys are case studies in the art of turning a biography into a weapon of influence and building ideological bridges where only walls of mistrust previously existed.

The “Dissident” Operator: Edward Lozansky

Edward Lozansky’s journey is a masterpiece of narrative construction. Presenting himself as a Soviet nuclear physicist turned dissident, he was able to capitalize on a fascinating personal story – his marriage to the daughter of a high-ranking general and his struggle to get her out of the USSR – to win sympathy and open the doors of political Washington.[15][16] This carefully cultivated legend allowed him to become a credible interlocutor for the American conservative elite.

But Lozansky was not just a storyteller. He was a builder of institutions, or at least, of institutional facades. He created a spider’s web of organizations with respectable names that served as platforms for a US-Russia dialogue that he could largely steer:

- The “American University in Moscow “: An entity with a prestigious name but a phantom substance, with no clearly identified faculty or curriculum, serving primarily as a vehicle for prestige.[17][18]

- “Russia House” and the “World Russia Forum”: Think tanks and annual conferences that became essential meeting places for politicians, diplomats, and businessmen from both countries, offering Lozansky a central role as a mediator and organizer.

Through these structures, he cultivated deep and lasting relationships with pillars of the conservative movement, such as Paul Weyrich, co-founder of the highly influential Heritage Foundation, and Senators Bob Dole and Jack Kemp.[17][18]

Lozansky, in fact, built the bridge on which the modern Russian lobby can now cross without hindrance.

The “Academic” Operator: Dimitri Simes

If Lozansky was the master of the network, Dimitri Simes was his intellectual counterpart. His background gave him almost unassailable academic credibility. Trained at the prestigious Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) in Moscow, he emigrated to the United States in 1973 and quickly established himself as a leading “Sovietologist.”[20][21] His analysis, perceived as coming from within the system, was highly sought after.

His rise was meteoric. He became an informal advisor to President Richard Nixon, accompanying him on trips to Moscow, which definitively established his position within the Republican establishment on foreign policy.[20][21] But his masterstroke was to take over as head of the Center for the National Interest (formerly the Nixon Center) and its journal, The National Interest.

Under his leadership, these institutions became extremely influential platforms for promoting a “realistic” foreign policy, often inclined toward greater accommodation of Moscow’s strategic interests.[22][23]

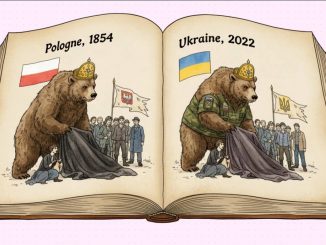

The careers of Lozansky and Simes reveal a fundamental and counterintuitive truth: Russia’s most successful influence operation of the late 20th century did not target the American left, traditionally more open to dialogue with Moscow, but rather the heart of the anti-communist bastion: the Republican right. How was such a reversal possible? The answer lies in a remarkably clever narrative pivot.

Lozansky and Simes never tried to sell Soviet ideology. They understood that the Cold War Republican Party, defined by its opposition to the USSR, was undergoing a major identity crisis after the fall of the Berlin Wall. So they sold a new, post-Soviet narrative that was perfectly aligned with this new trajectory.

In this narrative, Russia was no longer the atheistic communist threat, but a resurgent nationalist power, a bastion of “traditional values” in the face of Western decadence, and a potential partner against Islamic terrorism and “globalist” institutions.

This discourse resonated deeply with an American conservative movement that was itself increasingly nationalist, skeptical of international alliances, and engaged in a “culture war.” Lozansky and Simes did not have to change the GOP’s ideology; they simply aligned Moscow’s objectives with its natural evolution.

The “Putinization” of part of the American right was therefore not a hostile takeover, but a symbiotic convergence, a meeting of interests facilitated and orchestrated by these two visionary pioneers.

3. The Apotheosis of 2016: The NRA, a Wide-Open Door

The 2016 presidential election represents the culmination where decades of patient networking and infiltration finally bore their most spectacular fruit.[01][24] Russian interference, “widespread and systematic” according to the conclusions of Special Counsel Mueller, shook the foundations of American democracy.[24] To understand the mechanics of this operation, the Maria Butina case is a perfect microcosm, an exemplary case study of the Russian doctrine of influence in action.

Case Study on Vector Targeting: Maria Butina and the NRA

The operation led by Maria Butina, a young Russian activist, under the direction of Aleksandr Torshin, a high-ranking Russian official close to the Kremlin, was anything but improvised. It was based on a strategy of “vector targeting”: identifying not a direct political target, but a cultural and social organization serving as an entry point to the heart of conservative power. The chosen target, the National Rifle Association (NRA), was ideal.

- The Mirror Strategy: The first step was to create a Russian gun rights organization, “The Right to Bear Arms,” to mirror the NRA. This structure, although somewhat incongruous in a country like Russia where gun ownership is highly restricted, provided the perfect pretext for establishing an official “cooperative relationship” with its powerful American counterpart.[25][26]

“Authorized” (fake) demonstration in Moscow in 2012: 80 people gathered by Maria Butina — Photo Glenn Kates (RFE-RL). “Russia considers authorizing the carrying of firearms.” Russians have as much right to legally own a personal weapon at home as North Koreans!

- Infiltration through Seduction: For several years, Butina methodically cultivated the highest leaders of the NRA. She attended their annual conventions, presented awards, and participated in events, becoming a familiar and appreciated face.[26][27] The culmination of this phase was the organization, in 2015, of a trip to Moscow for a high-level NRA delegation. There, the American officials were received with great pomp, visiting arms factories and meeting with members of Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, including Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, who was then under American sanctions.[26][28]

- The Final Objective: Political Access: Once the NRA’s trust was gained, this relationship was used as a lever to penetrate the circles of the Republican Party and, above all, the nascent campaign of Donald Trump. Butina’s actions became more direct: she publicly questioned Trump at an event in 2015 about US-Russia relations; she obtained a brief meeting with Donald Trump Jr. in 2016; and her American partner and accomplice, Republican operative Paul Erickson, sent an email with the evocative title “Kremlin Connection” to a Trump campaign adviser, proposing to establish an unofficial communication channel.[25]

- The Fall: The operation ended with the arrest… financial flows reveals a two-speed strategy, much more sophisticated than a simple policy of spraying money around. On the one hand, a noisy and surprisingly ineffective official lobbying effort; on the other, a silent and patient campaign of elite capture through philanthropy and academic partnerships.[29][30]

The choice of the NRA as a vehicle for influence reveals an extraordinarily keen understanding of American society. Moscow did not target a heavily protected government agency or a political party as a whole. It targeted a cultural institution, a crossroads where money, political power, and, more importantly, a powerful and passionate political identity intersect.

The real target was not the NRA as a lobby, but its support base. This base represents a segment of the American population that is deeply rooted in conservative culture, inherently distrustful of the federal government and the “Washington elites,” and politically highly mobilized. It is a perfect incubator for narratives that pit “patriots” against a system perceived as corrupt. By infiltrating the NRA leadership, Russia gained direct access to this pre-mobilized and ideologically receptive network. It did not need to create division; it simply had to exploit and amplify an already existing sense of cultural and political grievance.

This strategy is akin to a form of political jiu-jitsu. It consists of identifying the most passionate and organized segments of a democratic society and using their own energy, structure, and fervor to advance a foreign agenda. More often than not, the rank-and-file members of these organizations are completely unaware that they are being exploited. The Butina case shows that the most effective Russian influence is not that which directly opposes American values, but that which manages to blend in, exploit them, and turn them against democracy itself.

4. The “realists” lounge: White-collar propaganda and the art of blaming the West

In The Russian Lobby in the United States, I highlighted a particularly insidious facet of Russian influence: “soft propaganda.”[01] This is not disseminated by anonymous trolls or state media, but by respected figures in academia and diplomacy, who come from the “realist” school of international relations. Names such as Henry Kissinger and John Mearsheimer, by offering analyses that, intentionally or not, align with the Kremlin’s narratives, lend intellectual legitimacy to the Russian position.[01] The case of John Mearsheimer, a professor at the University of Chicago, is the most emblematic of this phenomenon in the era of the war in Ukraine.

The deconstruction of Mearsheimer’s thesis

Mearsheimer’s central argument, hammered home in numerous conferences and articles that have gone viral, is simple and powerful: the primary responsibility for the war in Ukraine lies with the West, and more specifically with NATO’s expansion, which has cornered Russia and forced it to react.[31] This thesis, while appealing in its simplicity, collapses under rigorous critical examination.

- Ignoring Ukraine’s agency: The main flaw in Mearsheimer’s analysis is that it treats Ukraine as a mere pawn on the chessboard of the great powers, a passive object of geopolitics. It deliberately ignores the fact that Ukraine, like many Eastern European countries, has sovereignly and actively sought to join NATO for decades, not out of provocation, but out of a legitimate desire to protect itself from a Russian threat perceived as existential.[31]

- Uncritical use of Russian sources: Almost all of the evidence presented by Mearsheimer is based on a literal and uncritical reading of official Kremlin statements.[31] He takes Putin’s justifications at face value, ignoring decades of dezinformatsia and documented lies by the Russian state, from the initial denial of the presence of troops in Crimea in 2014 to fanciful claims about “biological weapons laboratories” in Ukraine.[31]

- Denial of Russian imperialism: Mearsheimer stubbornly refuses to consider Russian imperial ambitions as a main driver of the conflict. He dismisses Vladimir Putin’s explicit statements denying the historical legitimacy and even the existence of a sovereign Ukrainian state, or his comparison of himself to Tsar Peter the Great “retaking” Russian lands.[31] For Mearsheimer, Russia can only be a reactive power, never an aggressor driven by its own expansionist ideology.

- Empirical failure: His theory of “offensive realism” struggles to explain many real-world events, and its application to the Ukrainian case is contradicted by the facts. The invasion was launched at a time when Ukraine’s accession to NATO was at a standstill. Furthermore, Russian intelligence clearly made a “disastrous miscalculation,” expecting a quick victory and a favorable reception from the population, suggesting that the decision to invade was based on a distorted ideological view of Ukraine rather than on rational strategic analysis.[31]

Despite these glaring weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s thesis enjoys immense popularity.

His lectures are widely broadcast and his arguments are repeated ad nauseam, particularly by the Russian state media, which has found in him an unexpected Western ally.[31][32]

This phenomenon illustrates a key concept in Russian information warfare: “reflexive control.” This is a sophisticated technique that aims to manipulate an adversary into making decisions that are favorable to Russian interests on their own initiative. By presenting his thesis under a veneer of academic objectivity and intellectual rigor, Mearsheimer (and with him, part of the realist school) has succeeded in shifting the debate in the West.

The question is no longer “How can we counter Russian aggression?” but has become “Are we responsible for Russian aggression?”

John Mearsheimer (Self-portrait)

This shift is strategically disastrous for the West. It sows doubt, fuels internal divisions, paralyzes political decision-making, and erodes public support for aid to the victim, Ukraine. Attention turns inward, in an exercise of self-flagellation and guilt, rather than focusing on the aggressor’s responsibility. This is the essence of reflexive control.

Russia does not need to defeat NATO militarily if it can persuade the West to neutralize itself through doubt and intellectual division. In this context, the “realist” school, without necessarily being malicious, becomes an unintended but extremely effective force multiplier for the Kremlin’s strategic objectives.

5. Money, the lifeblood of gray warfare: Dollars, data, and donations

Moscow has spent millions of dollars to finance its influence operations, notably through donations from oligarchs to prestigious American institutions such as Yale, MIT, and the Guggenheim Museum.[01] However, a closer analysis of financial flows reveals a two-pronged strategy that is much more sophisticated than a simple policy of showering money around. On the one hand, there is loud and surprisingly ineffective official lobbying; on the other, there is a silent and patient campaign to capture elites through philanthropy and academic partnerships.

A Tale of Two Lobbies: Quantitative Analysis

Data from mandatory filings under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) allow for the quantification of the official lobbying effort and highlight a counterintuitive strategy.

An exhaustive analysis of the 2021 filings, conducted by the Quincy Institute, reveals a striking contrast.[33]

| Category | Russian Interests | Ukrainian Interests |

| Declared Expenses (2021) | > $42 million (including $38M for state media) | ~ $2 million |

| Number of Political Contacts | 21 | 13,541 |

| Cost per Contact (approx.) | ~ $2 million | ~ $148 |

| Main Actors | Mercury Public Affairs (for En+ Group) | Yorktown Solutions, Finsbury Glover Hering |

These figures speak for themselves. In 2021, Russian interests spent twenty times more than Ukrainian interests for an almost zero result in terms of official political contacts. The cost per contact for Russia is astronomical and borders on the ridiculous, suggesting that this declared lobbying effort is either just a facade or spectacularly incompetent.

Part of the explanation lies in a legal loophole: the distinction between FARA, which requires detailed transparency, and the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA), which has much less stringent requirements. Many firms prefer to register under the LDA, which allows them to conceal the true extent of activities directed by a foreign government.[33]

Nevertheless, the glaring ineffectiveness of official Russian lobbying raises a fundamental question: if this money is not buying direct influence in Washington, where is the “smart money” going? The answer lies in a longer-term strategy.

Case Study on Elite Capture: Viktor Vekselberg and MIT

The case of Viktor Vekselberg and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) perfectly illustrates this second, more discreet, and potentially much more damaging path. Viktor Vekselberg, a billionaire oligarch close to the Kremlin, was the architect of a major partnership between his foundation, Skolkovo, and MIT, aimed at creating “Skoltech,” a sort of Russian “Silicon Valley.”[34][35]

- The golden partnership: The agreement, worth $300 million for MIT, was launched in 2011. It was not a simple donation, but a deep collaboration aimed at building a research and entrepreneurship university modeled on the prestigious American institute.[34][36]

- Access to the top: Vekselberg was not just a distant patron. In 2013, he was elected to the MIT Corporation, the university’s board of directors, and was re-elected in 2015.[34][35] This position gave him not only immense prestige, but also a seat at the table of one of the world’s most important and influential scientific institutions, with potential access to cutting-edge research and future American technology leaders.

- The awkward unraveling: The relationship soured when the US Treasury Department sanctioned Vekselberg in April 2018, accusing him of advancing Moscow’s “malign activities.”[37] MIT then quietly “suspended” his membership on the board of directors and removed all mention of his tenure from its website.[34][37] Yet despite the sanctions and fears of espionage expressed by the FBI, MIT renewed its partnership with Skoltech for five years in 2019, before finally abandoning it after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[35][38]

The juxtaposition of FARA data and the Vekselberg case reveals the duality of Russia’s financial strategy. Official lobbying in Washington, costly and ineffective, acts as a decoy, a diversion that attracts the attention of the media and regulators. Meanwhile, the real influence campaign is taking place elsewhere, quietly. The goal is not to influence a vote on sanctions legislation next week. The goal is to integrate Russian interests and perspectives into the very elite institutions that shape future leaders, develop tomorrow’s technologies, and define research paradigms. It is a long-term investment in the “operating system” of American power. Focusing solely on FARA filings is like watching the magician’s right hand while the left hand performs the real trick.

Viktor Felixsovitch Vekselberg — Photo Alesh.ru

The deepest threat lies not in the offices of K Street lobbyists, but in the boardrooms and laboratories of America’s most revered institutions.

Conclusion: The specter of 2016 and perpetual vulnerability

There is no doubt that the “specter of 2016” will haunt America for a long time to come, and the national security apparatus was caught off guard by the scale and nature of Russian interference.[01] This conclusion remains acutely relevant, because while tactics evolve, the fundamental vulnerability of American democracy remains. The threat did not fade after 2016; it morphed, adapting to new technological realities and exploiting new vulnerabilities.

The new hunting ground: Targeting former civil servants

The McGonigal case highlighted the threat posed by corrupt senior officials after they retire. This vulnerability is now being exploited on an industrial scale. Foreign intelligence services, particularly Russian and Chinese, aggressively use professional networking platforms such as LinkedIn to conduct sophisticated recruitment campaigns targeting employees and, above all, former employees of the Department of Defense and other federal agencies.[13][39]

The modus operandi is well established. Fake recruiters or front companies offer lucrative and flexible consulting assignments, flattering the expertise of their targets and exploiting their potential frustrations or financial vulnerabilities, particularly after waves of departures or layoffs.[14][40] The bait is often abnormally high pay for seemingly innocuous work, such as writing reports on general policy issues. Gradually, the requests become more specific, pushing the target to disclose sensitive information, sometimes without even realizing that they are working for a foreign power.[13] This is the threat illustrated by McGonigal, but democratized and deployed on a large scale.

The West’s response: A mosaic defense

Faced with this persistent threat, the United States and its allies have deployed an arsenal of countermeasures, forming a mosaic defense that is robust in some areas but often fragmented.

- Direct action and disruption: The Department of Justice (DOJ) is actively working to dismantle disinformation infrastructure, such as seizing dozens of domain names linked to the “Doppelgänger” campaign.[41] At the same time, the Department of the Treasury is imposing targeted sanctions on individuals and entities at the heart of these influence networks.[42]

- Cyber defense: The NSA, FBI, and their allied counterparts continuously publish advisory bulletins detailing the tactics, techniques, and procedures of SVR and GRU cyber actors, urging network administrators to apply the necessary security patches.[43]

- Legislative and policy reforms: The US Congress regularly holds hearings and reviews proposed legislation aimed at strengthening FARA, closing lobbying loopholes (such as the LDA exception), and improving the security of electoral processes against foreign interference.[44][45][46][47]

- Long-term resilience: Beyond reactive measures, discussions are underway on building societal resilience. Think tanks and some government agencies are advocating a “portfolio approach” that would include strengthening media literacy, supporting local journalism as a bulwark against disinformation, and developing counter-narrative strategies to preempt hostile narratives.[48][49][50]

Ultimately, the United States is attempting to combat a holistic and ongoing campaign of political warfare with a fragmented toolkit consisting of legal, financial, and technical countermeasures. The Russian doctrine, often referred to as “hybrid warfare” and associated with General Gerasimov, is a concept of total conflict that blurs the lines between war and peace, using information, culture, economics, and subversion as weapons in their own right.[51][52][53][54] It is a state of permanent confrontation.

The American response, while powerful in its individual components, remains largely reactive and compartmentalized. It treats influence operations as a series of discrete problems to be solved— a hack here, a disinformation campaign there—rather than as a systemic and ongoing aggression. The comparison with Russian tactics in Europe is illuminating: while in the United States the strategy is to exploit hyper-polarization and culture wars, in Eastern Europe it can draw on historical grievances or Orthodox religious ties.[55][56][57][58] Tactics are always tailored to the specific vulnerabilities of the targeted society.

A comparison with Russian tactics in Europe is enlightening: while in the United States, the strategy is to exploit hyper-polarization and cultural wars, in Eastern Europe, it can rely on historical grievances or Orthodox religious ties. The tactics are always adapted to the specific vulnerabilities of the targeted society.

The inescapable conclusion is that no FARA reform or seizure of domain names alone can cure the fundamental vulnerability of the United States. This vulnerability is not primarily legislative or technical; it is societal. It lies in deep political polarization, a decline in public trust in its own institutions, and an information ecosystem that has become a playground for manipulators.

The Russian lobby did not create these cracks in the foundations of America. But it has demonstrated an exceptional ability to find them, to widen them, and to plant the seeds of doubt and discord within them.

The lasting challenge for Western democracies is not just to counter Russia, but to address the internal weaknesses that make its efforts so formidably effective.

Laurence Saint-Gilles

Sources and Legends

[*] Associate Professor of History, Laurence Saint-Gilles has been teaching “The Geopolitics of the Contemporary World” at Sorbonne University since 2003 and in the Master’s program “Dynamics of International Systems (HCEAI).” A Fulbright scholar, she has dedicated her thesis and numerous articles to Franco-American diplomatic and cultural relations, notably “The Cultural Presence of France in the United States during the Cold War, 1944-1963” published by Éditions L’Harmattan.

[01] Laurence Saint-Gilles, « Le lobby russe aux États-Unis« , Desk Russie, 13 mai 2023.

[02] Andrew S. Bowen, « Russian Military Intelligence: Background and Issues for Congress« , Congressional Research Service, 2 novembre 2022.

[03] Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), « The Russian Intelligence Services« , 19 octobre 2018.

[04] The White House, « FACT SHEET: Imposing Costs for Harmful Foreign Activities by the Russian Government« , 15 avril 2021.

[05] Robert S. Mueller, III, « Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election« , U.S. Department of Justice, mars 2019.

[06] U.S. Department of Justice, « Grand Jury Indicts 12 Russian Intelligence Officers for Hacking Offenses Related to the 2016 Election« , 13 juillet 2018.

[07] Andrei Soldatov, Irina Borogan, « The FSB’s Fifth Service: The Intelligence Branch That’s Tearing Russia Apart« , Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), 14 avril 2022.

[08] U.S. Department of Justice, « Former Special Agent in Charge of the New York FBI Counterintelligence Division Sentenced to 50 Months in Prison for Conspiring to Violate U.S. Sanctions on Russia« , 15 février 2024.

[09] Benjamin Weiser and William K. Rashbaum, « Ex-F.B.I. Official Who Investigated Trump’s Russia Ties Is Sentenced to Prison« , The New York Times, 15 février 2024.

[10] U.S. Department of Justice, « Former Special Agent in Charge of the New York FBI Counterintelligence Division Charged with Violating U.S. Sanctions on Russia« , 23 janvier 2023. URL:

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] William R. Evanina, cité dans « NCSC Director Warns of Foreign Influence Targeting US Government, Private Sector« , MeriTalk, 9 octobre 2020.

[14] Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), « Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community« , 6 février 2023.

[15] Will Englund, « The strange career of Edward Lozansky, who recruits Americans for the Russian cause« , The Washington Post, 24 novembre 2017.

[16] « From dissident to lobbyist: A Russian’s journey« , The Christian Science Monitor, 14 mars 2002.

[17] Ibid, The Washington Post.

[18] Anders Åslund, Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy, Yale University Press, 2019.

[19] World Russia Forum, « About the Forum ». URL: https://www.google.com/search?q=http://www.worldrussia.org/

[20] David K. Shipler, « A Russian Emigre’s View From The Inside« , The New York Times, 11 novembre 1984.

[21] Center for the National Interest, « Dimitri K. Simes, President & CEO« , Biography.

[22] Casey Michel, « The Pro-Russia Influencers Who Want to Mediate a Deal With Ukraine« , Politico, 10 mars 2022.

[23] Peter Beinart, « The Realist Revolt« , The Atlantic, 1er juin 2022.

[24] Voir Réf. 5, Mueller Report.

[25] U.S. Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, « Report on Russian Active Measures Campaigns and Interference in the 2016 U.S. Election, Volume 5: Counterintelligence Threats and Vulnerabilities« , 18 août 2020.

[26] Tim Mak, « How A Russian Gun Nut And A GOP Operative Planted The Seeds Of A GOP-Russia Alliance« , NPR, 21 mars 2019.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Peter Stone and Greg Gordon, « Gun rights group, with Russian ties, is a potent force in Washington« , McClatchy DC Bureau, 2 mars 2017.

[29] U.S. Department of Justice, « Maria Butina Sentenced to 18 Months in Prison for Conspiracy to Act as an Agent of a Foreign Government« , 26 avril 2019.

[30] Sharon LaFraniere, « Maria Butina, Russian Gun Activist, Is Sentenced to 18 Months« , The New York Times, 26 avril 2019.

[31] Pour la thèse de Mearsheimer et sa critique, voir Phillips Payson O’Brien, « The World John Mearsheimer Wants« , The Atlantic, 18 avril 2023.

[32] Paul D. Miller, « John Mearsheimer, the War in Ukraine, and the Dangers of Causal over-Simplification« , The Dispatch, 14 mars 2022.

[33] Eli Clifton, « Lobbyists for Ukraine’s interests vastly outgun Russia’s in DC« , Responsible Statecraft (Quincy Institute), 3 mars 2022.

[34] David L. Stern, « MIT has a Putin problem« , The Boston Globe, 27 août 2019.

[35] U.S. Senate, Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, « Federal Support for Research at U.S. Universities: A Case Study of MIT’s Relationship with a Russian Oligarch », Staff Report, février 2022.

[36] MIT News, « MIT and Skolkovo Foundation finalize collaboration« , 14 juin 2011.

[37] U.S. Department of the Treasury, « Treasury Designates Russian Oligarchs, Officials, and Entities in Response to Worldwide Malign Activity« , 6 avril 2018.

[38] MIT News, « MIT ends collaboration with Skolkovo Foundation« , 25 février 2022.

[39] FBI, « Foreign Intelligence Service and Perpetrators of Malign Foreign Influence Use Social Media to Target and Recruit U.S. Persons », Private Industry Notification, 11 octobre 2023.

[40] NCSC (UK), « Think Before You Link campaign« .

[41] U.S. Department of Justice, « Justice Department Seizes Dozens of U.S. Website Domains Used in Russian ‘Doppelganger’ Disinformation Campaign« , 31 mai 2023.

[42] U.S. Department of the Treasury, « Treasury Sanctions Malign Russian Actors Across the Globe« , 19 mai 2023.

[43] CISA, NSA, FBI, « Russian SVR Targets Network Devices and Email Accounts« , Alert (AA22-110A), 20 avril 2022.

[44] Brennan Center for Justice, « Reforming the Foreign Agents Registration Act« , 24 mars 2021.

[45] House Committee on the Judiciary, « Hearing on ‘Oversight of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) and Efforts to Counter Undisclosed Foreign Influence’ », 17 juillet 2019.

[46] Ibid, Brennan Center.

[47] CISA, « Election Security« .

[48] RAND Corporation, « Countering Russian Social Media Influence« , 2019.

[49] The Aspen Institute, « Commission on Information Disorder Final Report« , 15 novembre 2021.

[50] U.S. Department of State, « Global Engagement Center« .

[51] Mark Galeotti, « I’m Sorry for Creating the ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’ », Foreign Policy, 5 mars 2018.

[52] Janis Berzins, « The New Generation of Warfare in Russia », The National Defense Academy of Latvia, 2014.

[53] Peter Pomerantsev, Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia, PublicAffairs, 2014.

[54] Keir Giles, « Russia’s ‘New’ Tools for Confronting the West: Continuity and Innovation in Moscow’s Exercise of Power« , Chatham House, mars 2016.

[55] Heather A. Conley et al., « The Kremlin Playbook: Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe« , CSIS, 13 octobre 2016.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Alina Polyakova, « The Kremlin’s Trojan Horses: Russian Influence in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom », Atlantic Council, 15 novembre 2016.

[58] Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), « Winning the Information War« , 22 août 2016.

See Also:

- « La guerre grise : Dollars, data et donations » — (2025-0831) —

- « The Serpent » — 2025-0831) —

In-depth Analysis:

Russia is waging an insidious “grey war” in the United States, using money, data, and donations to influence American politics. This strategy relies on a complex network, the “Putinosphere,” which ranges from intelligence services to agents of influence and “useful idiots.” The case of Charles McGonigal, a corrupt high-ranking FBI official, illustrates Russia’s effectiveness in infiltrating elites. As early as the 1970s, pioneers built bridges between American conservatives and Russian interests. The infiltration of the NRA by Maria Butina in 2016 showed how a cultural organization can become a gateway to power. Financially, Russia combines costly and ineffective official lobbying with a more discreet “elite capture” through partnerships. This strategy exploits political polarization and declining trust in institutions, revealing a deep societal vulnerability in the United States.