The Franco-German epic is the story of a radical metamorphosis: the “hereditary enemy” transformed into the founding ally of Europe.

by Charles Meynier

It begins with the irony of 17th and 18th century France unwittingly arming Prussia through the exile of its talent and the export of its ideas. This set in motion a tragic 150-year spiral, where the humiliation of Jena was avenged at Sedan, and the “Diktat” of Versailles led to the revenge of 1940, devastating the continent.

The break came in 1945. Upon the ruins, visionary leaders chose reconciliation, with Berlin becoming its laboratory. During the 1948 blockade, French soldiers transformed from occupiers into protectors—a foundational act that anchored trust.

This trust made the Élysée Treaty possible and turned the pair into the engine of Europe. This history proves that hatred is not fate but a political construct, and that the strongest peace can be born from the ashes of the darkest war.

The Dual Legacy of the Enlightenment : Prussia in Arms, Bavaria as a State (4)

Table of Contents

by Joël-François Dumont — Berlin, Octobre 4, 2025

Introduction: A European Epic

The history of Franco-German relations is far more than a bilateral chronicle; it is a true “European epic.”[01] At the heart of this saga lies the spectacular metamorphosis of two nations, long perceived as “hereditary enemies,” into the founding pillars of the European Union.[01] For centuries, their destinies intertwined through a “frequently conflictual dialectic, marked by devastating wars, mutual humiliations, and antagonisms deeply rooted in the collective consciousness.”[01] This tumultuous relationship can be understood in three great dramatic acts that have shaped not only both countries but the entire continent.

The first act is one of cruel historical irony, where France, at the height of its power, paradoxically provided its future Prussian rival with the tools for its own rise. Through the exile of its blood and the export of its spirit, it unwittingly armed the nation that would become its main antagonist. The second act is a 150-year tragedy, a spiral of violence where each conflict sowed the seeds of the next. This was the era of the ideological construction of the “hereditary enemy,” a vicious cycle of humiliation and revenge that culminated in the total conflagration of World War II.

Finally, the third act is one of unexpected redemption, a radical break with the past. Upon the ruins of a devastated continent, a “visionary political will” made it possible to transcend centuries of hatred to build a solid alliance, of which the city of Berlin became the most powerful symbol.[01]

This article, which is supposed to summarize the previous three, aims to trace this epic, analyzing the deep mechanisms of antagonism and the extraordinary wellsprings of reconciliation that transformed a shattered mirror into a cornerstone of modern Europe.

Part I: The Shattered Mirror of Berlin: When France Armed Its Future Rival (17th-18th Centuries)

The history of Franco-Prussian relations is marked by a fundamental paradox: France, through its own political and cultural decisions, played a decisive role in the emergence of the power that would, centuries later, challenge and humiliate it. Berlin, the future capital of this Prussian and later German state, stands as a “shattered mirror reflecting a distorted and ironic image of its own genius.”[02] This process unfolded in two stages: a transfer of human capital, followed by a transfer of intellectual capital.

The Huguenot Paradox: Exiled Blood, Prussian Strength

The first major transfer of power from France to Prussia was demographic and economic. In 1685, Louis XIV’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes, an act of religious intolerance aimed at unifying the kingdom under a single faith, proved to be a strategic blunder with lasting consequences. This decision triggered the exodus of over 200,000 French Protestants, the Huguenots, who were a dynamic and educated part of the population. Skilled artisans, entrepreneurs, intellectuals, administrators, and military officers went into exile, depriving France of a substantial portion of its vitality.

At the same time, Frederick William, the Great Elector of Brandenburg, issued the Edict of Potsdam. This act of great political foresight offered refuge, privileges, and freedom of worship to the Huguenot refugees.

For Brandenburg-Prussia, a still sparsely populated and economically fragile state, this influx of talent was an extraordinary boon. The Huguenots revitalized Berlin’s economy, founded manufactories, modernized agriculture, and strengthened the administration. Their work ethic and technical skills were decisive in laying the foundations of future Prussian economic and bureaucratic power. Moreover, many of them joined the army, bringing their expertise and shaping the officer corps of an institution that would become the state’s spearhead.

Thus, through an internal decision, France offered its nascent rival the human capital it lacked—a first “transfer” that would prove to have grave consequences.[02]

The Enlightenment as a Weapon: The French Spirit in the Service of Raison d’État

The second transfer was intellectual. In the 18th century, the French Enlightenment “spirit” fascinated every court in Europe.[02] No monarch embodied this fascination better than Frederick II of Prussia, the “Philosopher-King.” A staunch Francophile, he made French the language of his court, his academy, and his correspondence, importing French genius to “polish his court, shape his state, and sharpen his political intelligence.”[02] The complex and “tumultuous relationship with Voltaire in Potsdam” is the most striking symbol of this intellectual appropriation.[02] Frederick II invited the philosopher to his court, seeking to claim the prestige of French thought for himself.

However, the paradox here is even more cruel. France was exporting a philosophy of reason, criticism, and individual rights that it “struggled to apply to its own aging monarchy.”[02] Frederick II, however, seized upon it with a radically different purpose. He did not use the Enlightenment to liberate his people, but to “rationalize his army, modernize his administration, and conduct an aggressive foreign policy.”[02] He adopted the methods of the Enlightenment while rejecting its moral purpose, transforming philosophy into a “weapon in the service of raison d’État” (reason of state).[02] Rationality, efficiency, and planning, advocated by French thinkers, became tools in his hands to optimize the Prussian war machine and centralize power.

This co-opting of the French spirit illustrates a profound dynamic: power lies not only in endogenous development but also in the ability to absorb and instrumentalize external capital.

Through its cultural influence, France provided Prussia with an intellectual software for modernization. Prussia, in turn, applied it with a rigor and a military finality that France itself never imagined. In short, “through the exile of its blood and the export of its spirit, France paradoxically supplied its future Prussian rival with the tools of its own power, a history lesson etched in the stones of Berlin.”[02]

The dual legacy of the Enlightenment: Prussia in arms, Bavaria as a state

The case of Maximilian, Count of Montgelas, is fascinating because it illustrates a transfer that was not paradoxical or militarized, as in Prussia, but rather a structural, direct, and extraordinarily successful transfer of ideas. This is the positive side of the influence of the French Enlightenment.

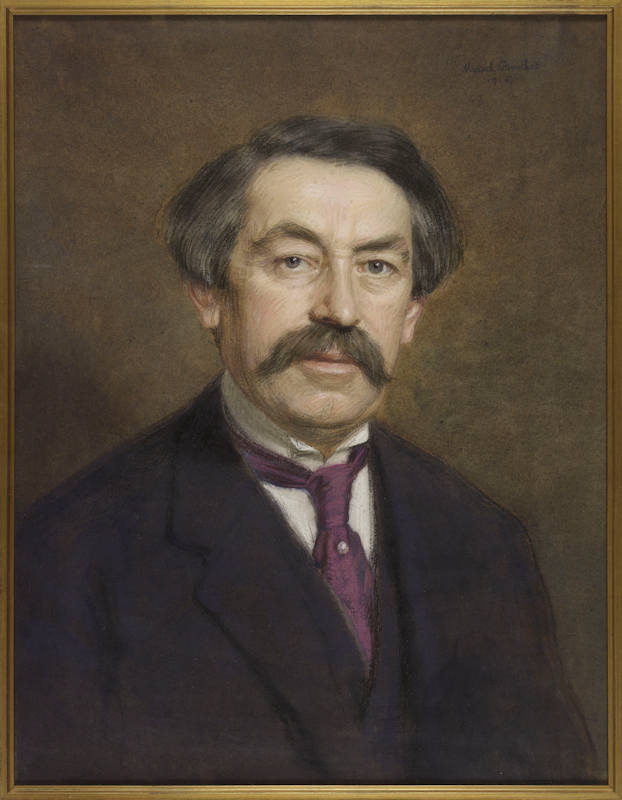

Beyond Prussia, the influence of the French Enlightenment found even more fertile ground in Bavaria, thanks to a Savoyard: the Count of Montgelas.

Maximilian de Montgelas, the true father of the modern Bavarian state, was a man steeped in French rationalism who brought about a revolution from above. Under his leadership, Bavaria adopted a consti-tution, abolished serfdom and torture, and centralized its administration based on a modern ministerial model. But his stroke of genius lay in the Dienstpragmatik, a visionary set of regulations for civil servants that replaced the right of blood with the merit of education. By basing access to public office on competence rather than birth or religion, he created a corps of dedicated and efficient civil servants.

Maximilien de Montgelas (1759-1839)

This Bavarian model, designed by a French mind, would serve as a template for the entire modern German administration, embodying a cultural and structural transfer of immense historical significance.

Part II: The Spiral of Humiliation: Constructing the “Hereditary Enemy” (1806-1945)

While the 17th and 18th centuries saw France unwittingly arm Prussia, the 19th and the first half of the 20th century were marked by direct and brutal confrontation. This period saw the birth and consolidation of the concept of the “hereditary enemy” (Erbfeindschaft). Far from being an inevitability, this notion proved to be an “ideological and political construct, fueled by repeated conflicts and the exacerbation of nationalisms.”[01] The central dynamic of this era was a “vicious cycle where the humiliation inflicted upon one nation inevitably sowed the seeds of a desire for revenge.”[01]

From Jena to Sedan: The Cycle of Revenge (1806-1871)

The starting point of this modern cycle is the Prussian humiliation at the hands of Napoleon. On October 14, 1806, at the battles of Jena and Auerstedt, the Prussian army, heir to the glory of Frederick the Great, was “literally annihilated by Napoleonic troops.”[01]

This “unprecedented military disaster” was followed by the occupation of Berlin and the 1807 Treaty of Tilsit, which dismembered the kingdom of Prussia and imposed harsh conditions upon it. For the Prussian elite and people, this event was experienced as an “intolerable degradation.”[01]

This crushing defeat had a profound psychological and political effect: it sowed the “seeds of a revanchist German nationalism.”[01] The confrontation with Napoleonic France took on a “particularly acrimonious turn, leaving deep and lasting scars.”[01] The desire for revenge simmered for over sixty years, fueling military reforms and an increasingly anti-French national sentiment. This cycle found its logical conclusion in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871.

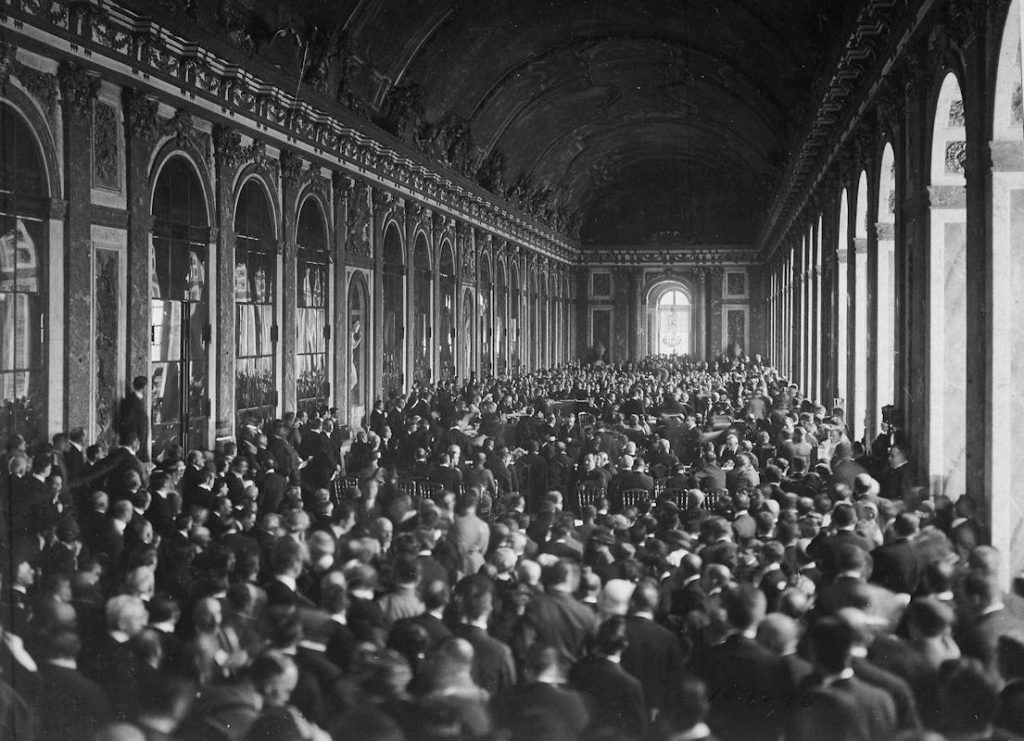

The French defeat at Sedan, the capture of Napoleon III, and, above all, the proclamation of the German Empire in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles on January 18, 1871, constituted the ultimate revenge for the humiliation of 1806. In turn, the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine fueled “French nationalism until 1914,” thereby setting the next turn of the spiral in motion.[01]

The “Diktat” of Versailles and Its Consequences (1919)

The cycle repeated itself with tenfold intensity in the 20th century. After four years of a horrific war, Germany was defeated in 1918.

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, was designed by the Allies, particularly a revanchist France, to permanently neutralize German power. However, its terms—territorial losses, crushing financial reparations, demilitarization, and especially the “war guilt” clause—were perceived by nearly all Germans as an unbearable national humiliation, a “Diktat” imposed by force.[01] This feeling of injustice and humiliation became a “powerful psychological and political engine” that undermined the Weimar Republic and served as fertile ground for the rise of Nazism.[01]

The Shattered Hope of Locarno: A Truce in the Spiral (1925-1929)

After the tensions of the post-war period, France isolated itself by seeking to apply the Treaty of Versailles alone. It lost British and American support when the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. The year 1923 marked the height of tensions with Poincaré’s occupation of the Ruhr and Hitler’s attempted coup in Munich.

The Franco-German impasse paved the way for appeasement. Under Herriot, MacDonald, and especially Stresemann, an era of dialogue began, leading to the Locarno Agreements, which marked Germany’s return to the diplomatic stage.

Yet, this trajectory toward conflict was not linear. A brief but intense glimmer of hope emerged in the 1920s, an attempt to break the cycle of hatred often described in retrospect as an “unfinished, failed, or illusory reconciliation.”[03] This effort was embodied by two visionary statesmen: French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand and his German counterpart, Gustav Stresemann.[04]

Together, they envisioned the Franco-German relationship as an instrument to preserve a still-fragile peace.[05]

Their diplomatic masterpiece was the Locarno Treaties, signed in October 1925.[05] Through this treaty, Germany recognized its western borders for the first time, including the loss of Alsace-Lorraine, and committed, along with France and Belgium, to no longer resort to war to settle disputes.[06][07] This act marked Germany’s return to the international stage as an equal partner, culminating in its admission to the League of Nations in 1926.[07][08] A cautious optimism, dubbed the “Spirit of Locarno,” swept through Europe.[06] For their efforts, Briand and Stresemann were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926.[05] Briand, the “pilgrim of peace,” famously declared: “Away with rifles, machine guns, cannons! Make way for conciliation, arbitration, and peace!”[07]

However, this hope was short-lived.[06] Stresemann’s untimely death in October 1929 deprived Germany of its most fervent advocate for reconciliation.[09] A few weeks later, the Wall Street Crash plunged the world into the Great Depression. The economic crisis revived nationalism and protectionism, rendering plans for European cooperation obsolete.[09] In Germany, resentment over the Versailles “Diktat,” never extinguished, was exploited by extremist parties. Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 and the remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936, in flagrant violation of the Locarno Treaties, sounded the death knell for this failed peace and set Europe back on the path to war.[08][10]

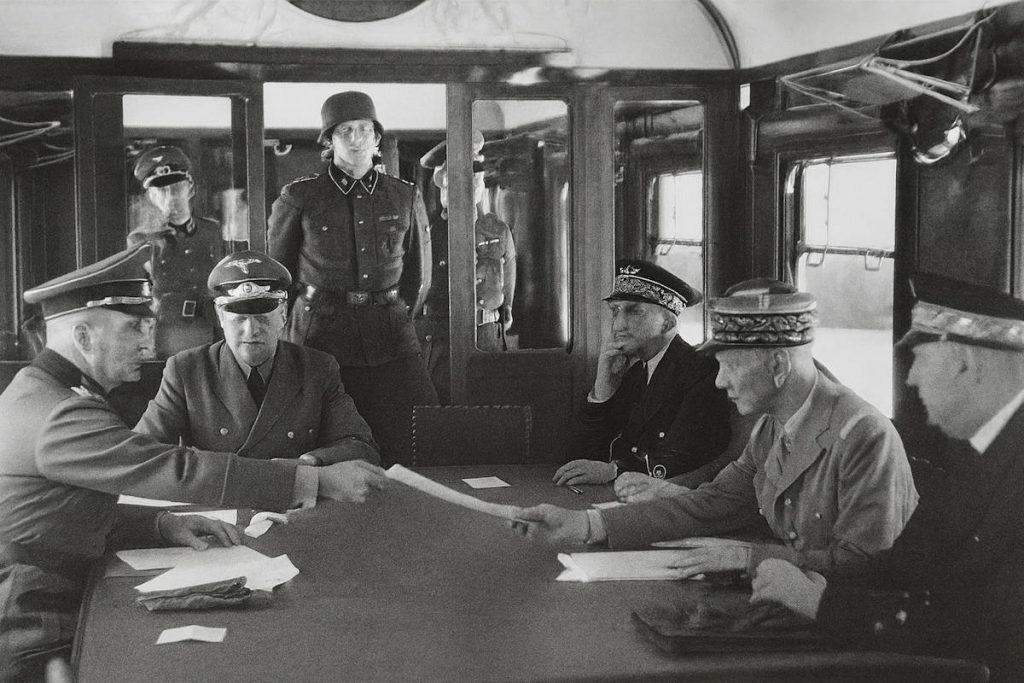

The Final Conflagration (1939-1945)

World War II, unleashed by Hitler, can thus be seen as the “paroxysm” of this spiral of destruction.[1] The symbolism was omnipresent. The German breakthrough at Sedan in May 1940 was experienced as a “reversed and aggravated repetition of the French defeat of 1870.”[01] Furthermore, Hitler demanded that the armistice of June 22, 1940, be signed in the same railway car and at the same location, in Rethondes, as the German armistice of 1918, meticulously staging his revenge. This history tragically demonstrates that a “peace founded on the humiliation of the vanquished is a precarious and illusory peace.”[01]

The following table summarizes this destructive cycle, where each humiliation calls for revenge in an escalating spiral of violence that ultimately engulfed the world.

| Event & Date | The Act of Humiliation (For Whom?) | The Revenge and Its Consequences | Key Phrase |

| Jena & Auerstedt (1806) | Prussia | The Prussian army is “literally annihilated.”[01] The Treaty of Tilsit dismembers the kingdom. | “Seeds of a revanchist German nationalism.”[01] |

| Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) | France | Defeat at Sedan. Proclamation of the German Empire at Versailles. Annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. | Fueled “French nationalism until 1914.”[01] |

| Treaty of Versailles (1919) | Germany | Loss of territories, crushing reparations, war guilt clause. | Perceived as a “Diktat,”[01] a “powerful psychological engine.” |

| Armistice of Rethondes (1940) | France | Hitler forces the signing of the armistice in the same 1918 railway car in Compiègne. | “Completed this spiral of destruction.”[01] |

The analysis of this period reveals that hostility was not inevitable. It was sustained by the instrumentalized memory of these symbolic humiliations. The true driving force of war was not just geopolitical or economic, but also psychological. It was the narrative of injustice and the desire to avenge the affront that allowed nationalisms to mobilize populations for ever more devastating conflicts. Breaking this cycle, therefore, could not be limited to a mere military armistice; it required shattering the very narrative of humiliation.

Part III: From Occupiers to Protectors: The Metamorphosis of an Alliance (1945-1994)

The end of World War II in 1945 marks a radical break. Upon the ruins of a continent and at the apex of a cycle of hatred, visionary leaders chose reconciliation. Nowhere was this transformation more visible and symbolic than in Berlin, the former capital of the Reich that had become the epicenter of the Cold War. It was there, in that divided city, that French soldiers underwent an extraordinary metamorphosis, transitioning from “occupiers to protectors.”[11]

Berlin, 1945: The Moment of Truth and Visionary Will

In the summer of 1945, French forces entered Berlin. Their presence was not a given. Initially excluded from the Potsdam agreements that divided the city into three sectors, France, thanks to the determination of General de Gaulle and the support of Winston Churchill, “carved out its own sector to become a key player.”[11]

French soldiers arrived as victors in an enemy capital that was 75% destroyed, where they had to manage a humanitarian crisis and oversee denazification.[11]

This moment of total victory could have been an occasion for renewed humiliation, perpetuating the cycle of vengeance.

Instead, it was the “moment of truth.”[11] The choice that was made, both in Berlin and at the highest political levels, was not one of retribution but of reconstruction—not only material but also political and moral. This attitude on the ground foreshadowed the “visionary political will” of leaders like Charles de Gaulle and Konrad Adenauer, who understood that the only way to ensure a peaceful future for Europe was to definitively break the logic of the hereditary enemy.[01] The French Forces in Berlin (FFB) were not content to be mere soldiers; they became “builders and agents of denazification,” laying the first stones of a new relationship.[11]

The Tegel “Stroke of Genius”: The Birth of the Protectors

The event that sealed this transformation was the Soviet blockade of Berlin in 1948-1949. By cutting off all land and water access to West Berlin, Stalin hoped to force the Western Allies to abandon the city. The response was the Berlin Airlift, an unprecedented logistical operation. While the United States and Great Britain handled the bulk of the transport of food and supplies, France played a decisive role on the ground—a role that would forever change its relationship with the Berliners.

West Berlin’s main airport, Tempelhof, was overwhelmed. A new one was needed, and fast. It was then that the French command took a bold initiative: to build an entirely new airport in its sector, at Tegel, in record time.

This was “not just a construction project, but a stroke of strategic genius.”[11] In just 90 days, with the help of the Berlin population, French engineers built a runway capable of handling the largest cargo planes.

This feat “broke the Soviet strangle-hold and ensured the success of the airlift.”[11] Through this act, France tangibly demonstrated its commitment to Berlin’s freedom.

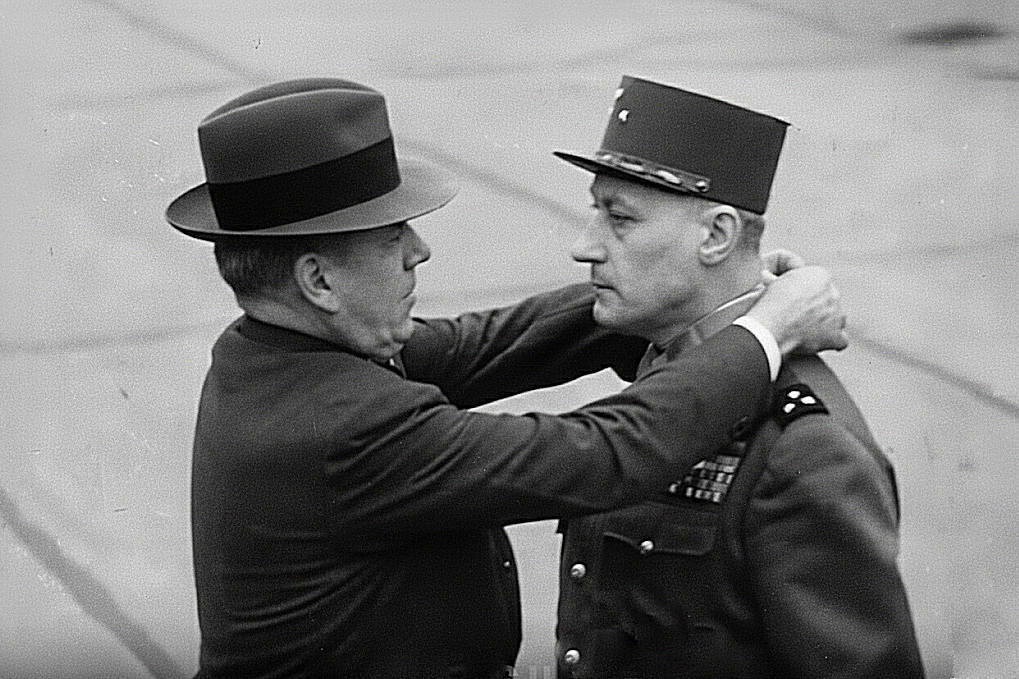

Général Jean Ganeval — Photo FFB

This period saw the emergence of heroic figures like General Jean Ganeval. Faced with Soviet radio towers that obstructed the approach to Tegel, he ordered his Soviet counterpart to dismantle them. When the Soviets refused, he issued an ultimatum and, upon its expiration, had the towers blown up with dynamite. When questioned by his allies about his methods, he simply replied, “With dynamite, my dear.”[11] In two days, this French general became the “hero of a city.”[11] The transformation was complete. The French were no longer occupiers; they had “helped save the city and guarantee its freedom.”[11]

Sealing the Friendship: From the Élysée Treaty to a United Europe

The trust born in the crucible of Berlin provided the foundation upon which political reconciliation could be built. The symbolic actions on the ground lent immense credibility to the political gestures that followed. General de Gaulle’s historic speech to German youth in Ludwigsburg in 1962, followed by the signing of the Élysée Treaty on January 22, 1963, with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, institutionalized this new friendship.[01]

This treaty was more than a declaration of intent. It established concrete and permanent mechanisms for cooperation at all levels: regular government consultations, youth exchange programs with the creation of the Franco-German Youth Office (OFAJ), and cultural initiatives like the television channel ARTE.[01] It even led to the creation of joint military units, such as the Franco-German Brigade, the ultimate symbol of the transformation of former enemies into “unwavering allies.”[11]

The goal was clear: to replace the notion of the “hereditary enemy” with the then-revolutionary concept of the “hereditary friend.”[01]

This reconciliation did not just pacify relations between the two countries; it became the engine of European integration. The success of this endeavor rests on this unique synergy between grand political acts and tangible proofs of solidarity experienced on the ground, as in Berlin.

Conclusion: A History Lesson Etched in the Stones of Berlin

The Franco-German epic, from centuries-old hostility to a founding alliance, is one of the most profound geopolitical transformations in modern history. It offers a universal lesson on the nature of international relations.

The journey from the “shattered mirror” of Berlin, where 18th-century France unwittingly shaped its Prussian rival, to the runways of Tegel Airport, where its soldiers saved that same city, is a powerful testament to the irony of history and the human capacity to change its course.

Three major lessons emerge from this history.

- The first is the demonstration of the futility and extreme danger of the “vicious cycle where the humiliation inflicted upon one nation inevitably sowed the seeds of a desire for revenge.”[01] From Jena to Versailles, from Versailles to Rethondes, this spiral proved that a punitive peace is an illusory peace.

- The second lesson is that the notion of a “hereditary enemy” is not an immutable fate but an “ideological and political construct.”[01] It can be deconstructed by a courageous and visionary political will, capable of looking beyond past grievances to imagine a common future.

- Finally, the Franco-German reconciliation shows that lasting peace is built on two inseparable pillars: bold political frameworks, like the Élysée Treaty, and concrete acts of solidarity that anchor friendship in the lived experience of peoples. The French presence in Berlin from 1945 to 1994 embodies this second pillar. In transitioning from occupiers to protectors, the French not only guaranteed the freedom of a city but, above all, shattered a centuries-old narrative of hatred.

The Franco-German story is thus proof that even the deepest antagonisms can be overcome, and that a future of cooperation can be consciously built on the ruins of the darkest past.

It is this lesson, etched in the stones of Berlin, that remains the greatest legacy of this unique relationship and the foundation of European peace.

Joël-François Dumont

Sources and Notes

[01] European-Security.com, « Forging Europe: How Centuries of Conflict Became a Core Alliance (2) » — (2025-0926)

[02] European-Security.com, « Berlin, Broken Mirror of France (1) » — (2025-0924)

[03] Cairn.info, “Franco-German reconciliation in the 1920s”.

[04] Chemins de Mémoire.gouv.fr, “Aristide Briand“.

[05] Sénat.fr, “Information report on the Franco-German couple“.

[06] GSsA.ch, “100 years since the Locarno Treaties“.

[07] Wikipedia.org, “Locarno Treaties“.

[08] StudySmarter.fr, “Summary of the Locarno Treaties“.

[09] Cairn.info, “Towards a united Europe? Aristide Briand, Gustav Stresemann and Franco-German cooperation in the interwar period“.

[10] LocarnoCittaDellaPace.ch, “History of the Locarno Treaties“.

[11] European-Security.com, « From occupiers to protectors, the French Forces in Berlin: (1945-1994) (3) » — (2025-0928)

See Also:

- « Zerbrochene Spiegel, gemeinsames Schicksal (4) » — (2025-1004)

- « Miroirs brisés, destins liés (4) » — (2025-1004)

- « Shattered Mirrors, Shared Destiny (4) » — (2025-1004)

- « Les Forces Françaises de Berlin (1945-1994) (3) » — (2025-0928)

- « Von Besatzern zu Beschützern: die FFB in Berlin (1945-1994) (3) » — (2025-0928)

- « From occupiers to protectors, the French Forces in Berlin: (1945-1994) (3) » — (2025-0928)

- « Berlin-Tegel 1948 : Le coup de génie français » — (2025-0927)

- « The 424 Flights That Rewrote History » — (2025-0927)

- « 1948: Der Genie-Streich von Tegel » — (2025-0927)

- « D’une hostilité séculaire à une alliance fondatrice (2) » — (2025-0926)

- « Forging Europe: How Centuries of Conflict Became a Core Alliance (2) » — (2025-0926)

- « Vom Gegner zum Partner: Das deutsche-französische Vorbild (2) » — (2025-0926)

- « Berlin, mémoire de France (1) » — (2025-0924)

- « Berlin, Gedächtnis Frankreichs (1) » — (2025-0924)

- « Berlin, Broken Mirror of France (1) » — (2025-0924)

- « Maximilian Joseph de Montgelas : un Savoyard père de la Bavière moderne » — (2022-0115)

In-depth Analysis:

The Franco-German epic is the story of a radical metamorphosis: the “hereditary enemy” transformed into the founding ally of Europe.

It begins with the irony of 17th and 18th century France unwittingly arming Prussia through the exile of its talent and the export of its ideas. This set in motion a tragic 150-year spiral, where the humiliation of Jena was avenged at Sedan, and the “Diktat” of Versailles led to the revenge of 1940, devastating the continent.

The break came in 1945. Upon the ruins, visionary leaders chose reconciliation, with Berlin becoming its laboratory. During the 1948 blockade, French soldiers transformed from occupiers into protectors—a foundational act that anchored trust.

This trust made the Élysée Treaty possible and turned the pair into the engine of Europe. This history proves that hatred is not fate but a political construct, and that the strongest peace can be born from the ashes of the darkest war.