On 14 July, an update to the National Strategic Review (RNS 2025) was published. This update, commissioned by the French President of the Republic, complements the work carried out in 2022. It proposes the actions needed to adapt our defence to a new, deteriorating environment and outlines the country’s overall defence and rearmament, including moral rearmament, of the nation. (Source SGDSN).[*]

Several questions arise: do we have the means to achieve our ambitions? Will we have the political will to implement them in order to right the ship after so many years of deliberate under-investment, so that France can, in the near future, hope to have the means to face a war of the intensity that the Russians are preparing in Europe for 2028-2030? As the 2022 national strategic review is being updated, Vice-Admiral (2s) Christian Girard [**] questions the foundations of French defence and the strategy that underpins it.

Table of Contents

by Vice Admiral 2s Christian Girard — Toulon, 25 July 2025 —

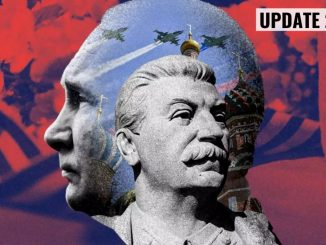

“Russia will drink communism like a sponge drinks ink ,” said General de Gaulle to Alain Peyrefitte on 10 September 1962. The collapse of the USSR in 1991 and the re-emergence of Russia as a genuinely Russian international player proved him right. We undoubtedly need to go beyond this observation to understand the nature of the current threat, which seems to be a reincarnation of the Soviet threat of yesteryear. Could it not be, quite simply, that the latter was in reality nothing more than the ideological packaging of Russia’s eternal geopolitical project? We believed that the threat would disappear with communism. That was a mistake. It has led to the current situation: European countries are caught between Russia’s imperial project and the American strategic shift, which is no less imperial in economic and political terms. Russia had already drunk the cup of communism under the Soviet Union. The death of communism could not be the death of a geopolitical project that was bound to reappear once the Russian economy regained sufficient strength.

It is in light of this reflection that France’s defence strategy for 2025 must be rethought.

Where have we come from?

The short-sighted ‘visionaries’ of the 1990s, who heralded the ‘peace dividends’, believed in good faith that the threat had disappeared. In fact, the economic collapse of the countries that made up the USSR considerably reduced their industrial and military capabilities. The remaining forces had lost their operational credibility despite maintaining impressive nuclear potential.

It took ten years to refit the cruiser Moskva, with the renovation work financed by the city of Moscow. Begun in 1992, they were completed in 2002. The ideological hostility between two antagonistic and incompatible economic and political systems should have disappeared.[01] This was not the case.

The French political establishment, across the political spectrum, rallied behind this opportunistic political vision, significantly reducing military budgets, especially at the turn of the 2000s. Europe and France appeared strategically ‘insularised’ by the disappearance of the continental threat. They no longer had to consider their security in any other way than in relation to what were referred to as ‘new threats’, which were security-related rather than military in nature.

These threats were directed against the internal order of society through actions originating outside the national territory.[02] Military means were only used as a backup to deal with them. However, it was also necessary also be able to project power or forces in international crisis situations to defend our interests or promote the universal values of peace and human rights, sometimes with a great deal of hypocrisy. The first Iraq War in 1991 had shown the need to professionalise the forces in order to be able to project them in overseas operations.[03] National service was suspen-ded and effectively abolished in 1996.

Vice-Admiral (2s) Christian Girard – Photo © DR

At the same time, the concept of defence was losing ground. It was subsumed under the broader concept of security, which was enshrined in the 2008 military programming law. Defence was no longer the priority issue for the life of the nation that the experience of the two World Wars had identified. It was reduced to its military component, neglecting all the other components that contribute just as much, in particular social cohesion, the link between the armed forces and the nation, the economy and industry.[04]

On a strictly military level, with nuclear deterrence providing the ultimate protection for our vital interests, conventional forces, especially those of the army, lost their raison d’être in engaging in conventional combat on the European continent. With the ultimate warning manoeuvre no longer necessary, the land component of nuclear deterrence was abolished. Long-range combat capability disappeared at the same time as it was hypocritically proclaimed that there was no more money for defence, as if this reality were not the result of political choices and will, thus condemning, for example, the construction of a second aircraft carrier to ensure the permanent availability of the naval air group.

The war in Ukraine has, in general, made leaders aware that a new strategic cycle has begun. After the Cold War and the dividends of peace, a response was needed to the new strategic reality. The military budget began to grow in 2017 on the initiative of the new President of the Republic, while Russia had taken possession of Crimea and the eastern border regions of Ukraine since 2014. The Russian threat is finally recognised today, more than ten years after the first acts of aggression against Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s autocratic regime is attempting to rebuild the collapsed empire, while US policy is becoming unpredictable and sometimes even hostile towards its former allies.

Where do we stand? What should our national defence policy and strategy be?

Many signs should have made it possible to anticipate this reality as early as 2008.[05] Unfortunately, it is not certain that European public opinion, even today, wants to abandon the comfort of burying its head in the sand, with certain political fringes finding every reason to justify Russian aggression and ready to give in to its demands in the name of so-called Western aggression in an updated version of the famous ‘die for Danzig’ slogan.

Should the principles laid down by General de Gaulle, which have remained unchallenged since then, be called into question? Is it enough to adapt the military tool to the new strategic environment, as was done between the first and second cycles, as described above, and in what way?

At the time of the 2017 presidential election, a study entitled “Refounding Defence ‘.[06] This analysis already mentioned the rise in international tensions caused by ’the development of the jihadist threat, Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria, China’s claims and actions in the China Sea, and the crises in the Middle East and Africa‘. It expressed the fear that ’it is the American initiatives – those of the new president –[07] that will lead either to complete disintegration or to a revival” with regard to the European project and the possibility of freeing it from American tutelage in the field of defence.

The principles established in the 1960s – national independence, decision-making autonomy, strategic functions divided between nuclear deterrence and conventional forces, participation in the Atlantic Alliance and the construction of a European Union – do not seem to be in question today, even less so than in previous years. The changing international strategic landscape, and particularly the recent missteps of US policy, have demonstrated their relevance at a time when US support for the Atlantic Alliance is becoming uncertain.

The heart of the matter is strategy, formerly known as resources, i.e. the choices to be made and the paths to be followed in order to achieve these general objectives in the current difficult economic and budgetary context. This is the part of the RNS 2025 that seems most uncertain, as it multiplies strategic functions and objectives, adding a tenth strategic function, influence, to that of 2022.

What should be done?

Prerequisites

There is one fundamental factor for restoring defence in the current environment that is not mentioned in the RNS 2025: its restoration to the place it should never have ceded.[08] It is the first of the state’s sovereign functions, as it is the ultimate guarantee of the nation’s existence and survival.

This recognition has many consequences, including receiving the budgetary priorities necessary for its funding and reconsidering the place of the military in society. It is necessary that they obtain the consideration they deserve from their fellow citizens and that the latter are attracted to serving the nation in the status that this implies. The first issue is that of recruiting professionals and ensuring commit-ment to the operational reserve. These two parameters demonstrate the citizens’ support for the defence effort, a prerequisite without which nothing is possible.

However, even if defence spending is given priority over social spending,[09] the fact remains that a nation’s strength and military power depend first and foremost on its economic and financial prosperity.[10] The deindustrialisation of the country and the poor state of public finances are worrying in many respects, including the revival of defence. There can therefore be no question ofopposing the financial and military spheres, as was systematically done until recently, but rather to strengthen one to support the other. This will require sacrifices in the social sphere, which can only be accepted if the first condition mentioned above is met.

A comprehensive national strategy is needed to guarantee the defence of the nation. Internal security is part of this strategy, as an element of national cohesion and resilience in the face of all forms of aggression, whether originating outside the country or stemming from internal divisions and vulnerabilities.

The defence of Europe

Beyond putting the country back in order, European defence is another dimension of national defence, now directly linked to the Russian threat, which is military in nature on the eastern borders of the Union, at sea and under the sea, in space, but also in many more insidious ways within our societies, including in France. These threats are conveniently referred to as ‘hybrid’.

France occupies a special position among EU countries in that it is the only one to possess nuclear weapons and several areas of excellence in defence industries and technologies: shipbuilding, nuclear armament and propulsion, aeronautics, space, submarine technology and missiles, particularly ballistic missiles.

However, it does not cover all areas of armaments necessary for conventional forces. Its current capabilities are limited in number and would not be able to cope with a long-term commitment. Nor is it geographically on the front line of the Russian military threat.

It must be acknowledged that the majority of European partners are equipped mainly with American weapons and continue to do so. This constitutes a formidable dependency that will not be easily overcome. At the same time, it is a considerable challenge for the American industry, which it cannot and will not want to abandon. It is therefore a central element in the transactional strategy adopted by the new US administration. It cannot be ignored. France can therefore only continue to urge its partners and the European Commission to develop and support a European industrial base and a European preference for military equipment purchases. This action will only be fully effective in the medium to long term. In the short term, US dominance will remain overwhelming. However, it acts as a kind of safety net against any attempts by the United States to withdraw from the European theatre.

This will not, however, prevent attempts to bring the operational needs of European armies closer together in order to coordinate planning and develop industrial cooperation despite the difficulties we are experiencing.

Under these circumstances, France has no choice but to support Eastern European countries with reinforced conventional forces adapted to the new challenges of warfare, as demonstrated by the war in Ukraine, drones, electronic warfare, the role of digital technology, space, intelligence and the internet. The objective of a deployable French division, put forward by the Chief of Staff of the Army, seems both realistic and weak in the face of the reality of the challenge.

NATO

The fact remains that Europe’s defence is provided by NATO under American control. This is the undisputed position of our partners. It seems impossible for France to ignore this, especially after the last summit in The Hague at the end of June, which gave no sign of any desire to break free from American tutelage. Nevertheless, informal consultation between the main European countries, including the United Kingdom, is absolutely necessary to try to bring about the famous European ‘caucus’ within NATO, which has always been rejected by the Anglo-Saxons. This is undoubtedly possible today, if the United Kingdom finally agrees to loosen its ties with the United States.

It is up to NATO to plan Europe’s entire operational defence against Russia. But it seems obvious that the main European countries must become more directly involved in this work and that they must claim leadership. Command of NATO forces in Europe must fall to a European general once US forces have been sufficiently reduced.

French nuclear deterrence

The issue of nuclear deterrence was recently raised by the President of the Republic. Nothing really new has emerged, apart from inappropriate and controversial comments. NATO recognises the role and contribution of French and British deterrence to the Alliance’s overall deterrence since the early 1990s, and successive French presidents, starting with President Pompidou, have expressed similar views, stating that French deterrence naturally takes into account the strategic situation of its European neighbours.

Some commentators have suggested that a strategic deterrent manoeuvre could be developed,[11] demonstrating our determination in the face of Russian aggression. It seems obvious that such a manoeuvre would pose many problems when it comes to deploying French air assets equipped with nuclear weapons beyond national territory, the first being acceptance by the host country.

The possession of nuclear weapons allows France to demonstrate its role in the defence of Europe while at the same time positioning itself and justifying to its partners a certain degree of restraint with regard to direct issues related to conventional forces and their ground engagement.

Ukraine

Faced with the immediate and very important challenge for Europe of supporting Ukraine, it seems necessary to mobilise, as previously indicated, all willing countries beyond Europe.[12] Unfortunately, this initiative, which had begun to take shape, seems to have come to nothing, as it was limited to the prospect of support for Ukraine after a ceasefire that did not materialise. The key to the outcome once again seems to lie in the hands of Donald Trump, who has authorised the resumption of defensive arms deliveries to Ukraine while giving the Russian president more time to continue his attacks.

France is expected to relaunch a new diplomatic initiative by countries willing to support Ukraine during this 50-day period, but it seems impossible to provide new military resources other than those that could come from Germany, if the German Chancellor does indeed authorise the deployment of Taurus missiles as he has stated.

After a cessation of fighting, the question of stabilising the situation and securing Ukraine remains unresolved. The resumption of French initiatives along the lines previously opened up is essential. This is primarily a diplomatic issue rather than a military one.

Army model

It is tempting, and some commentators are quick to do so, to declare that the priority for French conventional forces is now the European theatre, as the model of force projection is outdated. Our withdrawal from Africa under less than flattering conditions, regrettable as it may be, must not leave the field completely open to Russia, Turkey or China. The international situation can change. Our economic and strategic interests in Africa have not disappeared. It is therefore necessary to find new forms of ‘influence’ strategy that will be credible thanks to the existence of deployable intervention forces.

There is no reason to change the missions of the Navy. It guarantees nuclear deterrence through the SNLE programme, which is currently being renewed. It also guarantees the ability to project power from the sea against land, both in the European theatre and in any global crisis theatre where national or European interests are at stake, especially in Africa or the Indian Ocean. The French Navy also carries out sovereignty and security missions in the approaches to French territory and maritime economic zones under French jurisdiction, including the seabed. The resources are insufficient. They are only just beginning to be modernised but must be strengthened as a matter of urgency.

Conclusion

While most of the above considerations can be found in the RNS 2025 document, they do not appear with the clarity and specificity they deserve, no doubt for fear of alarming the reader. They are couched in a falsely bellicose administrative style that does not shy away from overusing neologisms, such as ‘hybridity’, without the concept having been clearly defined, or qualifying adjectives such as ‘robust’, which would be very difficult to translate into concrete terms in relation to the capacity in question. The multiplicity of objectives certainly contributes to diluting the message, which is intended to be mobilising in the face of a cautious or sceptical public. Beyond the objectives defined, the concrete reality of their achievement remains very vague.

A strategy is not just a catalogue of goals to be achieved, but also the proposed path to achieve them. Everything remains to be done in this area.

This was the case in 2022. The 2025 update was intended to justify the increase in the military budget.

Christian Girard

[*] Organised by the General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (SGDSN), a department of the Prime Minister’s Office, the work involved the participation of all ministries, associations of elected officials and the research community.

- 2025 National Strategic Review (French) — (2025-0714) —

- 2025 National Strategic Review (English) — (2025-0714) —

- 2025 National Strategic Review (German) — (2025-0714) —

[01] The author recalls the arrogance and contempt shown towards his hosts by the admiral commanding the Frounze Institute, who was received at the Naval War College in 1993 during his stay in Paris.

[02] Various forms of international trafficking, particularly drugs and illegal fishing.

[03] Foreign operations

[04] See ‘Defence and security, from the reversal of the hierarchy of concepts to national security strategy’ in ‘Cailloux stratégiques’ Ed de la petite Syrte 2022

[05] See Sylvie Kauffmann, Les aveuglés, Ed Stock, Elsa Vidal, La fascination russe ‘ Ed Arion

[06] In ’Cailloux stratégiques” Ed de la petite Syrte 2022

[07] Trump, elected for his first term

[08] See note 4 above

[09] The latter represent 39% of GDP, while defence accounts for only 2% and is trending towards 3%.

[10] ‘The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers’ Paul Kennedy Ed Payot

[11] La Vigie-TXT 25-07 A French strategic manoeuvre in early April 2025.

[12] https://european-security.com/guerre-dukraine-le-temps-de-la-diplomatie/

See Also:

- « La revue nationale stratégique 2025 : mise à jour ou refondation ? » — (2025-0725) —

- « The 2025 National Strategic Review: update or overhaul? » — (2025-0725) —

- « Der nationale Strategiebericht 2025: Aktualisierung oder Neugestaltung? » — (2025-0725) —

- « Національний стратегічний огляд 2025: оновлення чи переосмислення?» — (2025-0725) —

[**] Vice Admiral (2s) Christian Girard: A graduate of the École supérieure de guerre navale (Naval War College), where he was a professor, he was also a military advisor to the Directorate of Strategic Affairs, Security and Disarmament at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. A specialist in maritime operations, he was responsible forthe training of surface vessels under the admiral commanding the naval action force, where he later became deputy director general, a position he created. His last position in the Navy was deputy chief of staff for operations and logistics at the Navy General Staff. In this capacity, he was the first ALOPS, admiral in charge of naval operations.

Admiral Christian Girard is the author of four books: ‘L’île France – Guerre, marine et sécurité’ (France Island – War, Navy and Security), published in 2007 by Éditions L’Esprit du livre in the Strategy & Defence Collection. In 2020, ‘Enfance et Tunisie’ (Childhood and Tunisia) (not commercially available). In 2022, ‘Ailleurs, récits et anecdotes maritimes de la fin du XXe siècle’ (Elsewhere, maritime stories and anecdotes from the end of the 20th century) and finally, ‘Cailloux stratégiques’ (Strategic pebbles). To purchase ‘Ailleurs, récits et anecdotes maritimes de la fin du XXe siècle’ and ‘Cailloux stratégiques’, order on Amazon.

Analysis by Vice Admiral (2s) Christian Girard:

- ‘War in Ukraine: Time for diplomacy?’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2025-0515) —

- ‘What strategy should we adopt towards the United States?’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2025-0322) —

- ‘An initiative by liberal democracies in the face of the new geopolitical situation’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2025-0310) —

- ‘Early 2025: the real end of the concept of the West?’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2025-0216) —

- ‘Update on the war in Ukraine’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2024-1125) —

- ‘Breakthrough towards Kursk: a new strategy?’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2024-0902) —

- ‘The intersection of wars’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2024-0422) —

- ‘Two political and strategic questions for the 21st century’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2024-0309) —

- ‘Ukraine: rupture or continuity?’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2024-0309) —

- ‘Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, the American Clausewitz’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2024-0110) —

- ‘Vilnius: role-playing, contradictions, short-sightedness or hypocrisy?’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2023-0713) —

- ‘Reflections on cyber in the air-land space in Ukraine’ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2023-0224) —

- ” Towards the emancipation of Ukrainian strategy‘ — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2023-0603) —

- ’Relationship and antisymmetry between the situations in Ukraine and Taiwan” — Admiral Christian Girard (2s) — (2023-0422) —